STEP Matters 200

- Default

- Title

- Date

- Random

- The rainforest corridors along the gullies of northern Sydney have been called by many names as ecologists try to describe…Read More

- The Aboriginal heritage of northern Sydney reminds us that these precious environments around us have been valued and nurtured for…Read More

- Our local and regional environment owes so much to its geological heritage. We live in the Sydney Basin, an epicontinental…Read More

- In February 1805 botanist George Caley (sent out by Sir Joseph Banks) made an exploratory trip from Pennant Hills across…Read More

- Ku-ring-gai has a rich environmental history. Some even consider it to be the birthplace of the Australian conservation movement because…Read More

- Walking along hand built stone paths into the bushland property Ahimsa is a step back in time and an inspiration…Read More

- 1956 was my second year out from Sydney Teachers’ College where I trained as a physical education teacher. As a…Read More

- Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park is part of a geographic, geologic and eucalyptus sandstone bushland arc that encircles Sydney. This 12,963 hectare…Read More

- The early European history of the area that became Lane Cove National Park could be said to stem from an…Read More

- Sydneysiders are lucky to have several national parks within easy reach of suburbia. Their existence is thanks to a situation…Read More

- On the high ridges north of Sydney Harbour grew a tall, open forest of blue gums, blackbutts and casuarinas with…Read More

- Berowra Valley bushland stretches from south of The Lakes of Cherrybrook to the Hawkesbury River. The valley has a long…Read More

A Short History of the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest

The rainforest corridors along the gullies of northern Sydney have been called by many names as ecologists try to describe them and place them into a broader classification system, for example Temperate Rainforest (1), Sandstone Gully Rainforest (2), Coachwood Rainforest (3), Northern Warm Temperate Rainforest (4) and now more recently Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest (5).

While this rainforest forms a highly recognisable ecological community, the history and evolution of the individual plant species are all quite different.

Mosses and liverworts, not the extant species, were the first land plants and appeared around 470 million years ago (Ma) in the Ordovician. It has been speculated that their impact on the earth caused an ice age because of plummeting carbon dioxide (6).

Jumping forward to the mid Devonian (383–393 Ma) and a new group of plants is present, the ferns. Most of the earliest ferns are now extinct and most of our extant ferns date from only the last 70 million years, the late Cretaceous (7). Ferns of the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest include Common Maidenhair (Adiantum aethiopicum), False Bracken (Calochlaena dubia), Umbrella Fern (Sticherus flabellatus) and tree-ferns (Cyathea species). The origin of the Cyathea tree-ferns goes back to the Jurassic (201–145 Ma) (8) but the diversity in this tree fern family is unlikely to be older than the Palaeocene (younger than 66 million years).

The Umbrella Fern and Coral Fern (Gleichenia species) are considered an ancient fern family and date from at least the early Cretaceous (9) (approx 145 Ma).

Ancestry from millions of years ago: mosses from 470 Ma, Umbrella Fern from approx 145 Ma and Coachwoods from approx 34–28 Ma (photo Robin Buchanan)

The trees that dominate the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest are all flowering plants. The earliest fossil records of a flowering plant date from early Jurassic (10), more than 174 Ma but the diversification and dominance of flowering plants occurred from the Cretaceous (145–66 Ma) to more recent times (11). The main tree families of the rainforest include Myrtaceae, Cunoniaceae and Pittosporaceae.

Myrtaceae is an enormous family that has 1646 species in Australia and 3000 in the world (12). It is also very diverse with dry fruited plants typical of dry sclerophyll, such as Eucalyptus, and fleshy fruited plants typical of rainforests. It is primarily a southern hemisphere family with considerable northern extension. Crown Myrtaceae seem to date from only 95–84 Ma (13) (mid to upper Cretaceous). Species common in the Gallery Rainforest include Narrow-leaf Myrtle Austromyrtus tenuifolia, Grey Myrtle Backhousia myrtifolia, Water Gum Tristaniopsis laurina and Lilly Pilly Acmena smithii.

The Cunoniaceae is a small family with a Gondwanan origin and seems to date back to late Cretaceous. This family includes the trees Coachwood Ceratopetalum apetalum and Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia. Ceratopetalum and Callicoma had evolved by the early Oligocene (34–28 Ma) or earlier (14).

Pittopsporaceae, containing Mock Orange Pittosporum undulatum, seems to have originated in Australasia in the early Cretaceous (approx 117 Ma) (15).

Australia’s rainforests are a mere remnant of their former glory in the early Miocene (c23–16 Ma) when they were wide spread. By the late Miocene (10.5–5 Ma) the drying out of Australia had resulted in forests and woodlands across Australia and the remnants of the rainforests were confined to the wetter coastal areas of Australia (16).

In the northern suburbs there are also smaller stands of Coastal Warm Temperate Rainforest, Coastal Escarpment Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Headland Littoral Rainforest (5) but the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest is far the most common.

References

- Robinson, L (1991) Field Guide to the Native Plants of Sydney, Kangaroo Press

- Martyn, J (2010) Field Guide to the Bushland of the Lane Cove Valley, STEP

- Smith Ecological Consultants (2008) Native Vegetation Communities of Hornsby Shire

- Keith, D (2004) Ocean Shores to Desert Dunes, NSW NPWS

- Office of Environment and Heritage (2016) The Native Vegetation of the Sydney Metropolitan Area. Vol 2: Vegetation Community Profiles, ver 3

- Marshall, M (2012) First plants plunge earth into ice age New Scientist

- Pinson, J About Ferns American Fern Society

- Bystriakova, N et al (2011) Evolution of the climatic niche in scaly tree ferns (Cyatheaceae, Polypodiopsida) Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 165(1), 1–19

- Gonzales, J and Kessler, M (2011) A synopsis of the Neoptropical species of Sticherus (Gleicheniaceae), with descriptions of nine new species Phytotaxa 31, 1–54

- eLife (2018) Fossils suggest flowers originated 50 million years earlier than thought ScienceDaily

- Foster, C (2016) The evolutionary history of flowering plants Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 149(1&2) 65–82

- Centre for Biodiversity Research (2002) Australian Flora and Vegetation Statistics

- Stevens, PF (2001 onwards) Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, ver 14, July 2017 (and more or less continuously updated since)

- Barnes, R (1999) Palaeobiogeography, extinctions and evolutionary trends in the Cunoniaceae: A synthesis of the fossil record PhD thesis, University of Tasmania

- Nicolas, N and Plunkett, G (2014) Diversification times and biogeographic patterns in Apiales Botanical Review 80(1) 30–58

- Australian Museum (2018) Evolving Landscapes

Photo at the top of the page: dense foliage of Coachwoods and Black Wattle in the rainforest lining the creek between eucalyptus dominated slopes (photo Robin Buchanan)

Robin Buchanan

Caring for Country

The Aboriginal heritage of northern Sydney reminds us that these precious environments around us have been valued and nurtured for thousands of years. It reminds us that people can adapt and survive significant changes in climate. It also reminds us that some things can’t be replaced or regenerated.

It could be said that Aboriginal history has only recently gained a greater following in some parts of the wider community. Modern Australian history as a whole is quite short and it is understandable that a young society would choose to focus on the positives rather than delve into what is uncomfortable. An unfortunate consequence is that when we seek to learn more, the sources of information are fewer and less detailed.

The cataclysmic loss of life as a result of the smallpox epidemic in 1789 also meant a huge loss of traditional knowledge. The following decades of policies and attitudes that were unsympathetic towards Aboriginal people meant that the comprehensive environmental knowledge of the custodians for every tree and flower and hill and creek and bay would diminish.

Much of the work to learn about and protect Aboriginal heritage has focussed on the archaeology. The rock engravings found on Hawkesbury Sandstone platforms among Angophoras and Acacias have intrigued visitors and residents alike.

What could they mean? Macropods and marine species, boomerangs and shields, human and deity figures are represented in different areas.

Some were recorded and discussed in academic journals from the mid-1800s, with names suitable to the era, such as Mankind. A government surveyor recorded hundreds of engraving sites in the sandstone country in the late 1890s.

Throughout the twentieth century various individuals from the Australian Museum and elsewhere researched and tried to urge governments and the wider population to value and protect the engravings. Some engravings were individually protected through this and local activism, as well as the thousands that were deliberately and accidentally protected in the state and local government reserve system. The role of individual Aboriginal people in these campaigns is still poorly researched.

Then there are the rock shelters. Hawkesbury Sandstone again provided a medium for Aboriginal heritage to merge with the environment. What could be a spectacular natural landscape feature could also contain the hand stencils of family members from thousands of years ago, or the painted image of an important animal or its tracks. Even the ones we have forgotten locally, like emus and koalas.

Then there are the shell middens that shine along the now rapidly eroding foreshores of the estuaries and bays of this incredible landscape. Places where families gathered year after year to share food and stories. The middens tell us what people gathered and brought back to eat. They inform us of environmental and cultural change over time with variations in species and quantity. They invite Aboriginal people to feel welcome and connected.

Could it be said that the outsider’s interest in Aboriginal heritage and culture has been aimed in the wrong direction?

What does it matter if we record the engraved images of an animal if we have not recorded the wisdom of how to protect that species or its habitat?

Is it even fair to try to capture that wisdom but not nurture the people who have developed and implemented it over such an incredible period of the earth’s history?

We cannot go back and reinvent the past, only learn from it. Some knowledge that has been lost cannot be recaptured. A rock engraving destroyed or faded away is gone forever. However, as the bush regenerators know, the seedlings that are given the right conditions today will become tomorrow’s resilient canopy.

The climate is changing and the urban bushland is under increasing pressure. The many traditions of looking after one’s local area are more important than ever.

Our thanks go to David Watts and the friendly team at the Aboriginal Heritage Office.

Photo at top of page: David Watts with group on Sites Awareness walk, late 1990s

David Watts

Geology of the Sydney Basin

Our local and regional environment owes so much to its geological heritage. We live in the Sydney Basin, an epicontinental pile of sedimentary rocks several kilometres thick that was laid down in the Permian and Triassic periods between 300 and 200 million years ago, and our present landscape framework was created by tectonic uplift and erosion of its strata.

Abundant life in a chilly sea

We might think of our local landscapes in terms of its multiple sandstone tablelands, spurs and gorges. Their rocks were mostly laid down by fresh and brackish water in flood plains and estuaries, but the early history of the Sydney Basin incorporates a strong marine influence, and you can find abundant shelly fossils in numerous sites along the coast south of Wollongong. There's also much evidence that the sea at the time was icy cold and peppered with drifting, melting icebergs, and you can still view their dropped erratic, morainic boulders nestling amongst the fossils in cliffs and rock platforms. The mineral glendonite found down there only forms today in icy-cold sea floor mud – it was named after its discovery site at Glendon on the Hunter River. The global climate conditions captured by this older Sydney Basin suite is of national significance both to our scientific heritage and to a broader understanding of the earth's history.

A great extinction event

Towards the close of that chilly, early basin epoch, the seas gradually subsided and coal formed from the peat of boreal swamp forests, contributing historically to our region's strong economic base. But the coal story came to an abrupt end 252 million years ago with the great end-Permian extinction event, when massive volcanic outpourings on the far side of the globe bathed the planet in acidic gloom and warmed and dried its atmosphere.

The evidence is beautifully preserved in cliffs south of Newcastle (pictured), north of Wollongong and also in the Blue Mountains.

This key event should be much more widely recognised and understood as its effects are mirrored in current climate change and extinctions. Our local geological heritage carries critically important environmental messages for today.

Plain old sandstones reveal fascinating stories

Some of our local sandstones were sourced from a long way off. Research on the Hawkesbury Sandstone based on radiometric dating has matched grains of a mineral called zircon with the same mineral in igneous rocks of the Transantarctic Mountains. Antarctica was joined to Australia at that time, and while still a long way off, the scale of the river system implicated is well within that of many flowing across present day continents.

Australia's membership of the supercontinents of Pangaea and subsequently Gondwana was the beginning of a story that flows right through to the roots of our floral diversity. Clearly it underpins our natural heritage.

Our sandstone's floral diversity

Our sandstone landscapes are built largely from nutrient poor but iron- and quartz-rich rocks that support an incredibly rich flora, many of whose species benefit from the buffering action of iron against phosphorus toxicity. The floral diversities of sandstone heathlands and shrublands in places like the Royal and Ku-ring-gai Chase are only surpassed in Australia by those of south-west WA, an internationally recognised biodiversity hotspot. Long term, the heritage value of our local bushland outstrips that of any of the temporary creations of human activity, however functional or beautiful they might be, and it must be preserved at all cost.

Dinosaurs, volcanoes and diatremes

The earlier paragraph on the great extinction event might also have mentioned that this kick-started the evolution of the dinosaurs, which of course ultimately led to the birds. The dinosaur era peaked in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods between 200 and 66 million years ago before ending in that other great extinction event, and at that time the sedimentary rocks of the Sydney Basin were compacting and drying out.

But there was still enough water left in their pores and joints that when basaltic magmas trickled in from depth, it flashed it into superheated steam that shattered its way to the surface at numerous points around the region. In many cases the magmas wormed their way through the crevices of shattered rock to follow it to the surface, also to be blown to smithereens by explosive pressures. The volcano style of that time is known as a maar, and its feeding pipe a diatreme.

In our northern Sydney region we have the largest and best preserved diatreme in Australia in the Hornsby quarry. This has heritage value and is a geological site of international status. Fortunately it appears the filling of the quarry for the parkland project has preserved the upper faces and cleared them of debris, thus exposing the diatreme's classic layered structure (pictured).

Layering in the volcanic debris of the Hornsby diatreme

Photo at the top of the page: Ghosties Beach Munmorah: black coal followed by white sandstone band marks the extinction event

Dr John Martyn

Timbergetting in the Lane Cove Catchment

In February 1805 botanist George Caley (sent out by Sir Joseph Banks) made an exploratory trip from Pennant Hills across the upper catchment of the Lane Cove River and reported on the fine timber. Nine months later Governor King issued directions for a gang of convicts to be employed at the North Shore to procure ship timber.

A timber carriage with eight draught bullocks was conveyed to the work site in the government punt, attended by a competent number of hands. Thomas Hyndes, one of the original grantees of land at Wahroonga, and clerk and overseer to the superintendent of camp and gaol gangs, probably accompanied them to the site on the flat at Fiddens Wharf, on the northern side of the Lane Cove River at Killara.

From an administrative point of view the Lane Cove camp was a problem. It was located distant from Sydney and run by overseers who had not been tried and tested in Sydney under the watchful eye of the principal superintendent.

There were three overseers appointed and dismissed from Lane Cove between 1808 and 1814. It was during 1809 to 1814 that the camp was most productive. The main timbers logged were Blackbutt, Blue Gum and Iron Bark for building purposes and Casuarina for roof shingles.

Governor Bligh prepared material to erect some necessary buildings including a large barrack for soldiers and timber from the North Shore Camp was used to build the Parramatta Store, completed by the end of 1809, and the Commissariat Building in Sydney, begun in 1809. These no longer exist.

Macquarie visited the camp in May 1810 and found that the timber in the Lane Cove Valley between Hornsby and Roseville was getting scarce and observed that the camp would need to be moved elsewhere.

Macquarie’s first major project using Lane Cove timber was the building of a Light Horse Barracks and a new hospital, now Parliament House and The Mint. The numbers of draught cattle at Lane Cove were trebled in preparation for this major project.

Rafters at the southern end of The Mint showing a purlin (top horizontal timber) attached to the rafter using a tusk tenon joint (photo Ralph Hawkins)

In 1814 there were two overseers at Lane Cove; one for the men and one for the stock. There were four timber fellers who supplied eleven sawyers, seven shingle splitters, eight timber carriage drivers, four stockmen, two boatmen, two blacksmiths and a wheelwright. There were also two watchmen and five other labourers, making a total of 48 men.

The hospital, completed in 1816, has some of the last timber cut at Lane Cove. Soon afterwards the camp was re-located to Pennant Hills and the North Shore was described as follows by Alexander Harris:

I could not but take notice of the immense number of tree stumps. Each one of these had supplied its barrel to the splitter or sawyer or squarer: and altogether the number seemed countless. Several times I was induced to wander off the road down a grassy slope overshadowed by oak or gum or ironbark, to where I saw the form of a hut, in the hope of getting a light for my pipe; but found only some deserted pit or falling hut, with docks and other such plants growing all around, as is usually the case when the grass has been destroyed to the very roots.

Photo at the top of the page shows timbers in The Mint that were probably sawn from timber cut in Lane Cove during 1812 and 1813; the ceiling joists are all numbered in Roman numerals (photo Ralph Hawkins)

Ralph Hawkins

Annie Wyatt’s Conservation Ethic and the National Trust

Ku-ring-gai has a rich environmental history. Some even consider it to be the birthplace of the Australian conservation movement because it was here that one resident, Annie Forsyth Wyatt, called for a National Trust (NSW) to be founded.

Gordon resident, Annie Wyatt (1885–1961) became a strong force in the emerging conservation movement, collaborating with many other key Sydney conservationists of the 1930s. Annie Wyatt was very insistent that the early National Trust (NSW) be a force in protecting the natural environment:

… to safeguard and govern the national state parks, national monuments and reserves of the state.

Annie Wyatt, grew up when there was deep concern about the loss of many of Australia’s forests. As a young woman she witnessed the ‘wanton destruction’ of the trees, bushlands, forests, woodlands and fine colonial houses on Sydney’s Cumberland Plain, when she lived at Rooty Hill as a young girl.

However, Annie Wyatt became a conservationist ‘activist’ after being incensed when she saw a Ku-ring-gai Council truck dumping garbage into the creek below her home in Gordon in 1927. Distressed, she quickly gathered her neighbours together.

This led to her forming the Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League which aimed ‘to safeguard the natural charms of the municipality’ and in particular to promote Australian native trees.

The League organised school essay competitions and tree planting ceremonies that included celebrating ‘tree lover’ Joseph Maiden (1859–1925), the Director of the Botanical Gardens and a pioneer advocate for eucalyptus forests.

Underneath the magnificent lemon-scented gum tree along Henry Street, Gordon, in the Annie Wyatt Park, next to Gordon Station, lies a plaque dedicated to Mr and Mrs Charles Musson. The Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League planted this eucalyptus in memory of Charles Musson (1856–1928), Gordon resident and teacher-lecturer at the Hawkesbury Agricultural College. Charles Musson was a great enthusiast for the new school subject – nature study – that was being introduced into the school curriculum in the early 20th century.

The Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League inspired others to form their own tree lovers’ leagues in places such as Lane Cove, Mosman and Orange.

Annie Wyatt and the Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League, went on to work with many other conservationists in the 1930s including Charles Bean (1879-1968), revered WW I war correspondent and historian, and founder of the Parks and Playground Movement. Charles Bean was active in promoting the green-belt around Sydney with parks and playgrounds including the Lane Cove and Garigal National Parks (former Davidson).

David G Stead (1877–1957), the founder of one of the first organisations to protect native wildlife (the Wildlife Preservation Society) in 1909, was supportive of Annie Wyatt’s motion to form the National Trust at the Save the Trees Conference in 1944. This conference arose from the deep concern about the massive clearing of forests happening across the country.

Annie’s son Ivor Wyatt (1915-2004) followed his mother’s conservation efforts, and became president of the National Trust working with David G. Stead’s wife, botanist and teacher-lecturer Thistle Y Harris (1902–90), to promote the flora and fauna sanctuary and environmental education centre – Wirrimbirra – at Bargo.

Annie Wyatt, was an unashamed ‘ardent tree lover’. She rejected the notion of ‘progress’ that emerged as the dominant ethos after WW II that demolished swaths of colonial buildings and land cleared massive bushland across the state.

When Annie Wyatt formed the National Trust of NSW in 1945 she wanted an organisation that would protect monuments, houses and landscapes for perpetuity. She modelled it on the English National Trust which was fighting to protect its own significant buildings, monuments and landscapes from being destroyed by encroaching industrialisation towards the end of the 19th century.

The National Trust became an important counter voice opposing the post war calls for modernity and ‘progress’ that was knocking down so much history and nature.

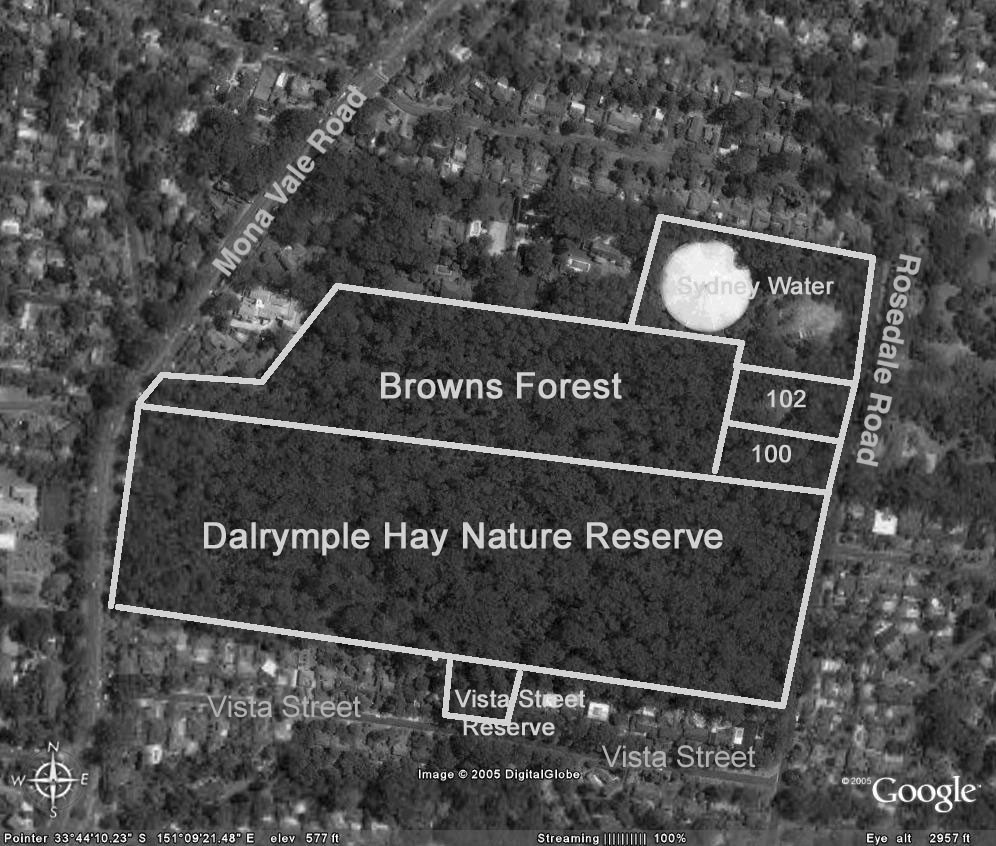

When Annie Wyatt saw the threat to the Dalrymple Hay Forest on Mona Vale Road, Pymble/St Ives in 1934 she worked with the ‘tree mayor of Ku-ring-gai’, Cresswell O'Reilly (1877–1954) to raise funds to purchase 11.5 acres to prevent the subdivision of Dalrymple Hay Forest, Mona Vale Road, St Ives in 1934. Cresswell O’Reilly would go on the chair the first meetings of the National Trust of Australia (NSW) formed in 1945.

Professor Eben Gowrie Waterhouse (1881–1977), of Eryldene, Gordon, also supported Annie Wyatt in this Ku-ring-gai forest campaign and presented the petition to save the Blue Gum High Forest to Ku-ring-gai Council. The community was again galvanised into campaigning to protect this unique and precious forest when it was again threatened with development from 2004–07.

Annie Wyatt’s conservation ethic continues to this day in the fight to protect Sydney’s urban bushland.

Photo at the top of the page is of the Tree Lovers’ Civic League planting in 1949 (courtesy National Trust of Australia (NSW) Archives)

Janine Kitson

Ahimsa: A Story of Bushland Protection

Walking along hand built stone paths into the bushland property Ahimsa is a step back in time and an inspiration for the future. It is also a remarkable testament to the former owner Marie Byles.

Gifted to the National Trust of Australia (NSW) over 40 years ago by Marie Byles, this 3.5 acre bushland property at Cheltenham in the Upper Lane Cove Valley is now listed as a state heritage item. Ahimsa adjoins Lane Cove National Park and is part of a large area of bushland surrounded by urban development.

Marie Byles was a visionary woman well ahead of her time. She was the first female to practice law in NSW, a mountaineer, explorer and avid bushwalker, a committed conservationist, a feminist, author, and original member of the Buddhist Society in NSW.

Marie was a passionate protector of bushland, whether from development, roads, weeds, or uncaring government officials. In 1938 she built a simple fibro and sandstone cottage on the property for her home on a rock ledge overlooking the beautiful surrounding bushland. The name of her home Ahimsa means harmlessness, a Buddhist and Hindu spiritual doctrine and Sanskrit word. This name reflects her belief that we are not separate from the world around us, and the natural environment should be respected and protected from harm.

Later in 1947, Marie designed the nearby Hut of Happy Omen which was built by friends and volunteers to accommodate a range of people and activities, including visiting Buddhists, bushwalking groups, conservationists and social gatherings.

Ahimsa is little changed in over half a century, and represents the physical expression of the life and values of Marie Byles. She left the land to the National Trust to protect its bushland in perpetuity, and in the public interest. The significance of the property is its realisation of Marie’s lifestyle and beliefs, and strong connection with current ideas about sustainable living, mindfulness, meditation and protection of the natural environment.

Ahimsa is a place that is important in the story of the conservation of Sydney’s bushland. An easy walk from the railway station, it is a place of peace away from Sydney’s hustle and bustle. The Hut of Happy Omen is available for use by people and groups compatible with the values of the property, by arrangement with the National Trust.

Friends of Ahimsa is working with the National Trust of Australia (NSW) to support future management of the property and to make Ahimsa accessible as a place that tells the story of its former owner and contributes to the realisation of Marie Byles’ dreams and values.

Children’s Art at Ahimsa on Sunday 28 April 2019 provides an opportunity for children between 7 and 11 years of age and their carers to appreciate the Ahimsa bush.

Although Ahimsa faces challenges for the future, including how to effectively maintain its bushland, heritage values and buildings, Marie Byles’ vision of simple living and protection of nature remains an inspiration. It is hoped that future generations will continue to use Ahimsa to learn about and reflect on Sydney’s bushland heritage, and the people who were instrumental in protecting it.

To find out more about Friends of Ahimsa, the conservation and management of the property, or to be placed on the Friends of Ahimsa contact list for future events and activities, please email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Martin Fallding has a lifelong association with Ahimsa as a neighbour and family friend of Marie Byles. He has had a long involvement in bushland conservation and is currently the president of Friends of Ahimsa.

Camps for Girls at West Head in the 1950s

1956 was my second year out from Sydney Teachers’ College where I trained as a physical education teacher. As a young 21-year-old I was very excited to get the opportunity to apply to be seconded from the NSW Education Department to the National Fitness Council programme. The boys’ programme was run at Juno Head and Little Marley. The girls’ programme was at West Head where an army base had been built during World War II.

The programme ran from Tuesday to Thursday for one or two schools each week. A teacher from each school was asked to attend, but this seldom happened. Generally, I would have about 20 girls, but I recall one time when I had 44 girls on my own!

On Tuesday morning at 9 am the girls would come to the Nat. Fit Office with their food and clothes. I would issue each of them with a Paddy Pallin four pocket A frame canvas backpack and an ex-army groundsheet. I would then show them how to pack their tins of food and usually an enamel plate and mug.

We would then all set off to walk to York Street to catch the double decker bus to Palm Beach. The trip took an hour and a half to the old wharf on Pittwater where we caught the 12 o’clock ferry to Big Mackerel Beach. Then it usually took about one and a half hours to walk up to camp which was about 300 feet above sea level. The girls used to find it hard going as their packs often had tinned food and they were not familiar either with a bush track or carrying a backpack.

It was a very pretty walk as it wound around the steeply sloping hillside of excellent Hawkesbury sandstone flora looking opposite to the Barrenjoey tombola. Just before the final climb up to West Head there was a waterfall which had to be negotiated by sidling along a narrow ledge.

It was a steep climb up the last 150 feet to the camp at the top where a tired group of girls would be greeted by the camp caretaker Stewart Pitts and Mrs Pitts. A retired couple who had built a cottage in Big Mackerel Beach. Both had a broad Scottish accent and they always had a cup of tea in their kitchen for me.

There was no electricity at camp apart from a generator that supplied lights at night. Perishables were put in a kerosene refrigerator. The girls slept in a 30 bed dormitory of former army bunks which had a horsehair mattress on a wire base. At the southern end there was had a huge fuel stove which I recall I had to use on a couple of occasions when it was too wet to cook outside. It was extremely smoky when the fire was lit.

When they were all settled in we would have a short walk to gather firewood up the dirt road towards Commodore Heights. I would explain some of the early European history to explain where all the names came from and show them remnants of the old military occupation during World War II, when over 500 men were stationed to protect the important rail and road bridges further up the river, linking Sydney with industrial Newcastle and its strategically important steel works.

The views were and still are magnificent, looking north up to Gosford and the Central Coast, and opposite to the striking Barrenjoey Lighthouse and the old Custom House on Pittwater.

After gathering firewood for their group, they learnt how to make a tidy wood pile and later how to build a cooking fire in the grates provided near the great rock outcrops on the western side of the mess hall. As many of the girls were from inner city areas, camping and outdoor cooking and washing up were not familiar tasks.

The toilet was a pit toilet or ‘long-drop’ at the end of a pathway back from the camp. The huge septic tank from the wartime was not available then. Water came from a tank.

The first evening we had team games in the mess hall. Lights out was at 9 pm. For many of the girls going to the toilet after dark was quite scary; as were all the strange animal calls at night, especially when possums had an argument on the tin roof. For many, they had not been away from street lights and there were no outside lights at the camp. Settling down at night was quite a challenge for some!

On our second day we went out bushwalking for the day to see Aboriginal engravings or to visit the many delightful creeks, or beaches on the Hawkesbury River. Flint and Steel and Hungry beach being favourite places.

Usually we would see a koala in the trees on Commodore Heights. There was so much of interest in the history and in the vegetation and wildlife. Occasionally, we would scramble down under the old camouflage nets and steep wooden stairs to the gun emplacements near the shoreline of the river. By about 3 pm I would aim to be back at camp to gather firewood for a campfire. Making doughboys, campfire singing and skits prepared by the girls were our evening entertainment.

On the last morning after breakfast we had a general clean-up, then we retraced our steps back down to the ferry at Mackerel Beach, then across to the city bus and a walk to Bridge Street after a great time at Three Day Camp.

In retrospect, this was a great time for nature-based learning and for appreciation of our potential World Heritage, Sydney Basin Sandstone Flora and Fauna. Since the National Fitness Office was taken over by the Department of Sport and Recreation, I feel that school education has lost its appreciation of local geology, flora and fauna-based learning which was then available to a few.

Sadly, schools have generally lost the experience of the joys of bushwalking, and the intrinsic mutual benefits of understanding how our natural heritage and our human health and well-being are inter-connected with the health and well-being of our unique natural heritage.

Click here for an interesting history of pre-war attempts to develop West Head. We are thankful that appreciation of our bushland has changed!

Click here for an account of West Head’s World War II history.

Janet Fairlie-Cuninghame

Time for Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park to be World Heritage Listed

Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park is part of a geographic, geologic and eucalyptus sandstone bushland arc that encircles Sydney. This 12,963 hectare national park is on the Hawkesbury Sandstone Plateau of northern Sydney. It is connected via other national parks to the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, which in turn is connected to the Royal National Park, south of Sydney.

The Sutherland Shire Environment Centre have been campaigning for the Royal National Park to be World Heritage listed for some time. They argue that the Royal has such cultural heritage importance as it marks the beginning of the global national park movement. The Sutherland Shire Environment Centre even argue that the Royal is the first national park in the world because it was the first to be called The National Park. US’s Yellowstone (1872), used the term ‘national park’ to acknowledge that it was administered by the federal government and not the state government.

Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park is also one of the first national parks in the world to be formed for the intrinsic value of nature. In 1894, it was the second national park declared in NSW. Its corporate seal – Natura Ars Dei or Nature is the Art of God – also expresses a spiritual connection to nature.

The driving force behind Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park was Eccleston Du Faur (1832–1915), a 19th century national parks advocate, adventurer and patron of the arts.

Eccleston Du Faur belonged to the 19th century Sydney intelligentsia and cultural elite who supported the creative endeavours of artists and explorers who ‘believed’ in this new land. Although born in England, du Faur was awe struck by the sandstone beauty of the Blue Mountains and Ku-ring-gai Chase. He played a key role in protecting the Blue Mountains’ Grose Valley because he believed it was one of the most beautiful places in the world.

In 1875 he employed the photographer, Joseph Bischoff, to join him, along with artist WC Piguenit, on an expedition to sketch, paint and photograph the Grose Valley, near Govetts Leap Falls. He planned to send Bischoff’s photographs to the 1876 Centenary Exposition in Philadelphia, USA. He wanted the world to see the Blue Mountains because he believed its spectacular scenery was unrivalled and even surpassed Yellowstone National Park in beauty.

Du Faur was also concerned about Sydney’s fastly disappearing wildflowers and made sure the park’s first by-laws had laws against the cutting of wildflowers. Regretfully this was not strong enough to stop the removal of 4000 waratahs, taken in one month in the post WW II years. The Trustees also prohibited the defacement and destruction of Aboriginal rock art sites and middens in the park.

Recently the Friends of Ku-ring-gai Environment (FOKE) have met with STEP to discuss how they can work together in putting forward the claim for World Heritage listing Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park – one of the first national parks in the world.

Janine Kitson

The Early Days in what is now Lane Cove National Park

The early European history of the area that became Lane Cove National Park could be said to stem from an exploratory visit to the Lane Cove River by George Caley in 1805. Caley was employed as a plant collector by Joseph Banks and was the first person to make a systematic study of eucalypts. He reported on the quality of the trees in the Lane Cove River valley and it is thought that as a result a convict timber camp was set up at what later became Fiddens Wharf.

One of the convicts employed at the camp was William Henry. He arrived in 1801 on the Earl Cornwallis, and no doubt obtained a good knowledge of the valley while working as a timber getter. After Henry was emancipated Governor William Bligh promised him a grant of 1,000 acres in an area which now includes much of the lower park and West Lindfield. Henry took up the grant and started a vineyard on a portion of the area. Unfortunately for him Bligh became somewhat distracted with the Rum Rebellion, the grant was never confirmed and eventually around 1850 Henry was thrown off the land as the government of the day prepared to sell it.

Some say that another famous Australian identity, John MacArthur had schemed to ensure that William Henry suffered because he had supported Bligh during the rebellion.

However, that was not the end of his family’s connection, his granddaughter Maria married Thomas Jenkins and in 1852 they purchased a portion of the land originally held by her grandfather. It was this family who held the property right up until 1937 when it was purchased by the government to form the basis of the national park.

The farm or orchard was known as Millwood, the house Waterview and the small stone building we now know as Jenkin’s Kitchen was built around 1855, separately from the house, as was often the case at that time when there was a fear of fire burning down the main building. Ironically the main building burnt down in 1943 after the incorporation of the area into the park, and although the kitchen has been affected by fire it is still with us.

After the recent renovations, which include a new roof and extensive work to the sandstone, there is every hope that it will remain as a focal point at the park headquarters for many years.

Invitation

Congratulations to STEP on reaching the milestone of the 200th issue of your magazine.

We at Friends of Lane Cove National Park also have a milestone coming up: the 25th anniversary of our founding. Many of you will know that this came about after the devastating fires in early 1994. However, that was not the start of bushcare in the park, a dedicated group had already been working in Carters Creek since 1991.

On 25 May we are gathering at the park to celebrate our 25 years and also to officially open Jenkins Kitchen which Friends have renovated with the aid of a Heritage Near Me grant. The grant is particularly designed to return heritage buildings to a form that can be accessed by the public. In this case the building, which is thought to be the oldest building in Ku-ring-gai, will be used at an interpretation centre illustrating its past use as a kitchen while acting as a source of information about the flora and fauna of the park.

On 25 May we are gathering at the park to celebrate our 25 years and also to officially open Jenkins Kitchen which Friends have renovated with the aid of a Heritage Near Me grant. The grant is particularly designed to return heritage buildings to a form that can be accessed by the public. In this case the building, which is thought to be the oldest building in Ku-ring-gai, will be used at an interpretation centre illustrating its past use as a kitchen while acting as a source of information about the flora and fauna of the park.

We would like to extend an invitation to anyone who has been a volunteer in the park or member of Friends of Lane Cove National Park in the past (and who we may have lost contact with) to come along and help us celebrate.

We will meet near the park headquarters at noon. Refreshments and a barbeque lunch will be provided, and it will be a good chance to catch up with old friends.

If you intend to come, please let us know at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to help us with the catering.

Photo at the top of the page is Jenkin’s homestead 1895 (photo Ku-ring-gai Library)

Tony Butteriss

Garigal National Park — Bantry Bay’s Early Days

Sydneysiders are lucky to have several national parks within easy reach of suburbia. Their existence is thanks to a situation where much of the land was too steep or inaccessible to build on in the early days. However the bushland was the setting for plenty of activity before its value for conservation and public benefit was recognised. Bantry Bay is a prime example.

Garigal National Park in only 8 km from the centre of Sydney. It covers about 2,200 hectares of bushland, comprising the valley of Middle Harbour Creek and its tributaries extending as far north as Mona Vale Road at St Ives, the slopes along the northern side of Middle Harbour as far as Bantry Bay and Wakehurst Parkway. The largest part is in the catchment of Narrabeen Lakes.

Bantry Bay is the only bay in Sydney Harbour that is not readily accessible from the land because of steep valleys, but access by water is a different story. Bantry Bay is the last deep water inlet to retain the character similar to that before European settlement.

The first European incursion into Bantry Bay was a bullock track, down which timber from Frenchs Forest was hauled to a wharf on the eastern side of the bay and shipped to other parts of the harbour.

In 1879 the Bantry Bay area was set aside for public recreation. By the start of the 1900s, the eastern side of Bantry Bay had been turned into a popular pleasure ground, complete with dance hall, picnic ground, a dining room and several summer houses. The Balmain New Ferry Company, operated by John Dunbar Nelson, promoted the area as a secluded, scenic and romantic retreat for the residents of an increasingly urban Sydney.

Early in the 20th century the safe storage of explosives became a concern. Bantry Bay was surveyed as a possible site because of the ease of transport by water and its seclusion. While Bantry Bay solved the thorny problem of where to safely locate a magazine complex in Sydney, it alienated the reserve from the public to whom it had been originally dedicated. Despite a storm of protest, including from the newly-created Warringah Shire Council, the land was dedicated for explosives storage in 1908.

The site was expanded over the years, in particular during World War I. The magazines were operated by the state government. They stored explosives for public works, including the Sydney Harbour Bridge and underground rail tunnels, and commercial purposes such as mining.

The site was taken over by the Allied Forces during World War II. Its final development comprised various magazines where the explosives were received, sorted and stored as well as an office, two jetties, numerous sheds and testing laboratories.

After the war, the difficulty of site access and the cost of maintenance led to the site’s closure in 1964 and since then the site has mostly been allowed to deteriorate.

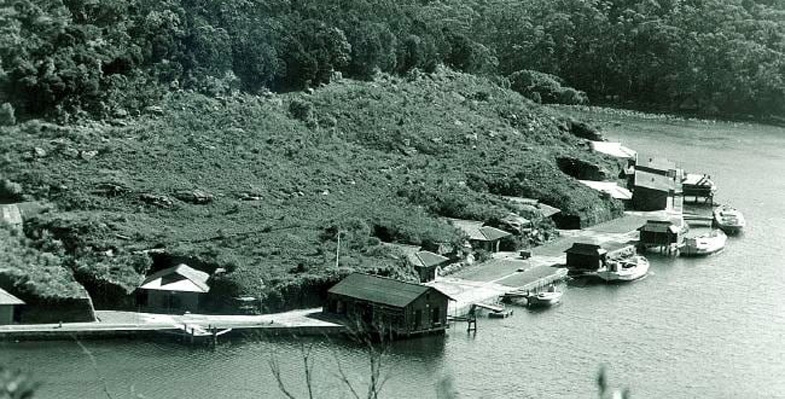

The hillside above the magazines that is covered in low vegetation in the photograph is now fully revegetated and the area is fenced off. The easiest place to see the old magazines is from the other side of the bay at Wharf picnic area.

The hillside above the magazines that is covered in low vegetation in the photograph is now fully revegetated and the area is fenced off. The easiest place to see the old magazines is from the other side of the bay at Wharf picnic area.

The buildings on the western side of Bantry Bay are architecturally significant both for their rare and specialised design and as examples of the public utility architecture of Federation Sydney, most of which is now either gone or threatened. They have been classified by the National Trust (1975).

A detailed description of the significance of the complex of buildings is set out in the draft Conservation Plan of Management (see details below). It identifies the Receiving Magazine as the most significant structure on the site but acknowledges that it may not be possible to repair. The design of the buildings is such that they cannot be adapted for a wide variety of uses without their significance being compromised. Access difficulties and the current lack of utilities may also cause problems for anyone interested in re-using the site. However they could be accessed by a trail from the Magazine Track or from a jetty.

Sources

Manly Daily (2016) The Former Explosives Complex that is now Part of a National Park

MacRitchie, J (2008) Bantry Bay, Dictionary of Sydney

Garigal National Park Plan of Management (2013) NPWS

Bantry Bay Conservation Plan of Management (draft) (2002) prepared for the NPWS by Graham Brooks and Assoc, Taylor Brammer Landscape Architects, Mary Dallas Consulting Archaeologists

Photo at the top of the page is Bantry Bay in 1972 (source Manly Daily 22 September 2017)

Jill Green

Preservation of Blue Gum High Forest in St Ives

On the high ridges north of Sydney Harbour grew a tall, open forest of blue gums, blackbutts and casuarinas with a moist understorey of shrubs, ferns, creepers and orchids. The largest remnant to survive the timber industry, orchards and spread of suburbs remains at St Ives. Threats of fragmentation necessitate repeated community campaigns to avoid further loss.

In 1925 this remnant of tall forest was purchased as a demonstration forest and named after the commissioner for forests, Dalrymple Hay.

Browns Forest which then extended to surrounding roads, was reduced by subdivision into 1 acre blocks for housing when neither the NSW government nor Ku-ring-gai Council purchased it. What remains was saved by community pressure led by Annie Wyatt of the Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ League, the mayor Cresswell O’Reilly and the Forest Preservation Committee. The 11 acres without a street frontage was purchased in 1934 by council for 1460 pounds, less 310 pounds from the owners if an undertaking was given to dedicate the land as forest reserve. Council completed the purchase with 350 pounds from public donations and covenanted Browns Forest as ‘forest reserve for all time’.

In 1946 land was resumed for water storage although the reservoir was not built until 1974.

100 and 102 Rosedale Road were owned by Prof Room from 1938. He built a house on the uphill part of 102 leaving the remaining portion forested. Following the deaths of Prof Room and his wife the property was sold in 1990 and the new owners submitted to council a nine lot subdivision on the 1 hectare.

People power needed again

Ku-ring-gai Bushland and Environmental Society, the National Trust and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service submitted objections, saying, due to the condition of the forest that the land must be purchased for conservation. Council rejected the subdivision but did not have the funds to purchase the land.

In 1997 Blue Gum High Forest was gazetted as an endangered ecological community in Schedule 1 of the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995.

In 2000 the 1 hectare was sold again and in 2002 a 12 lot subdivision was submitted to council, which was again refused. The owners appealed against council’s decision to the Land and Environment Court. The appeal was dismissed:

… because of its inability to provide a sufficient asset protection zone … and also its impact on the endangered Blue Gum High Forest ecological community.

Yet another development application was submitted in 2004 for a single dwelling on 100 Rosedale Road. By July 2005 council had rejected this development application having received 60 objections.

Strong community support was now building for conservation of all of the Blue Gum High Forest at St Ives. A coalition of community organisations, led by STEP Inc, formed the Blue Gum High Forest Group which led walks through the forest, distributed leaflets, gave talks, wrote begging letters seeking donations and lobbied council. Fortunately most councillors were by then wanting to save this 1 hectare of forest but the purchase price was over $2million.

The properties, 100 and 102 Rosedale Road, were advertised by Colliers International for sale on the international market. However, by the closing date at the end of May they had not been sold.

Meanwhile the Blue Gum High Forest Group had surveyed all the remnants of Blue Gum High Forest, and with council, submitted an application to the Commonwealth to list the Blue Gum High Forest ecological community as ‘critically endangered’. Several mayors, NSW and federal politicians, government officials and journalists were walked through the St Ives Blue Gum High Forest.

Breakthroughs in 2005

The Commonwealth Minister for Environment and Heritage announced the listing of the Blue Gum High Forest ecological community as critically endangered. NSW also upgraded the listing.

Half of the 1 hectare was purchased by NSW Rail Infrastructure to offset loss of BGHF due to railway upgrades near Hornsby.

Council agreed to apply for funds from the National Reserve System and this was supported by the Federal Member for Bradfield.

The BGHF Group had raised donations of $72,000 which impressed the councillors.

Yet again, in 2007, another development application was submitted for a house on 102 Rosedale Road and again council rejected it on the grounds of impact on the ‘critically endangered’ Blue Gum High Forest ecological community. Fortunately the Commonwealth contributed $350,000 to assist council’s purchase of this last half hectare of Blue Gum High Forest at St Ives. The whole was added to the National Reserve System which includes protected areas across Australia including national parks, nature reserves, historic sites and private land under voluntary conservation agreements.

It was time for a party. Yet another exhausting battle to prevent loss of another piece of our natural heritage from being destroyed had been won. Community care for the Blue Gum High Forest continues with bushcare groups working with National Parks and Wildlife Service and Ku-ring-gai Council. To join in contact Ku-ring-gai Council.

Click here for more details on the Blue Gum High Forest.

Nancy Pallin

The History of National Park Estates in Berowra Valley

Berowra Valley bushland stretches from south of The Lakes of Cherrybrook to the Hawkesbury River. The valley has a long history of reservation, from 1934 up to 2012. The valley currently contains a complex system of national parks, a regional park, nature reserves and an Aboriginal area.

The basis of Muogamarra Nature Reserve goes back to 1933 and this park, from Cowan to the Hawkesbury River, is still enjoyed for six weekends of the year by the public.

In 1964 Elouera Bushland Natural Park (640 hectares) was formed from bushland stretching from Boundary Road, Pennant Hills, to just north of the Riffle Range at Hornsby. For 24 years this park was managed by a group of honorary trustees appointed by the Minister of Lands. The first president of the Trust in 1964 was the Hon Max Ruddock MP, father of the present mayor of Hornsby Shire Council.

In 1987 Berowra Valley Bushland Park was gazetted. It included Elouera Bushland Natural Park but it now extended all the way to Berowra and Hornsby Shire Council was appointed trustee by the Minister for Lands.

Further land acquisitions were made and in 1998 these lands became Berowra Valley Regional Park, an area of over 3800 hectares. Because of the high value of this land, the majority of the land was reclassified as a national park in 2012 (3876 hectares). Only 9 hectares remain as regional park along some suburban interfaces, specifically to allow dog walking.

The Friends of Berowra Valley grew out of all these changes and in 2004 published A Guide to Berowra Valley Regional Park. They have also published a map of the park, available from STEP.

While Elouera Bushland Natural Park was evolving to a National Park, other areas were being incorporated into the reserve system. In 1979 Marramarra National Park, an area of 11,759 hectares, was gazetted in the northern part of the Valley, from just north of Berowra Waters to the Hawkesbury River and west to Old Northern Road.

In 1997 Mount Kuring-gai Aboriginal Area (0.6 hectares) was reserved and in 2017 a Statement of Management Intent was written to help conserve its special cultural value.

Dural Nature Reserve was reserved in 2003 from the former Dural State Forest. With additional lands added, it is now 35.58 hectares.

With the complex history of reservation go the names of many extraordinary people. Over the years many people have lobbied, collected data, and been part of the dissemination of information to the public, but to me three names stand out.

In 1967 Dr Joyce Vickery (1908–79), a botanist with the Royal Botanic Gardens, donated over 100 acres (40.5 hectares) of land in the Hornsby Valley for inclusion into Elouera Bushland Park.

In 1967 Dr Joyce Vickery (1908–79), a botanist with the Royal Botanic Gardens, donated over 100 acres (40.5 hectares) of land in the Hornsby Valley for inclusion into Elouera Bushland Park.

John Tipper (1886–1970), an engineer, leased the land to become Muogamarra Nature Reserve in 1933 and opened it to the public in 1935. In 1987 it became the Nature Reserve of the same name managed by National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Robert (Bob) Salt was awarded a Centenary Medal in 2001 and in 2011 he was awarded an OAM for service to conservation and the environment through a range of organisations in the North Sydney region (see photo). He has worked for the conservation and effective management of Berowra Valley bushland since 1962 to the present day.

Not all the bushland in the valley is managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service. Hornsby Council manages large areas, there is Crown land and there is an abundance of private bushland as well. More battles for the valley may be before us.

Photo at the top of the page is the opening of Berowra Valley National Park in 2012 at Crosslands: Bob Salt, Robyn Parker (Minister for the Environment), Matt Kean (Member for Hornsby) and Robert Browne (Hornsby Councillor) (both photos Noel Rosten)

Robin Buchanan