Displaying items by tag: synthetic turf

Norman Griffiths Oval synthetic turf debacle continues

We recently published an article in STEP Matters about the sorry tale of construction of the new synthetic playing field at Norman Griffiths Oval in West Pymble. Four months later and nearly a year after the oval was due to be completed by November 2023, the work on the stormwater detention system is still continuing. According to council’s website the completion date is now due to be November 2024.

The original cost estimate was $3.3 million. It is now $5.5 million.

Initial pollution incidents

In April 2024 there was a disruption to the works after heavy rain caused a lake to develop on the site. Bushcarers who have been working along Quarry Creek that leads from the field discovered large quantities of sediment-laden water going down the creek. This has happened numerous times. The process of draining the lake must not impact this creek that leads to Lane Cove National Park.

After this flooding was reported to the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) the EPA made several inspections. They noted three pollution incidents:

- 6 to 8 April – the north-east wall of the sediment basin had collapsed and damaged a pipe which resulted in an uncontrolled discharge of sediment laden water into Quarry Creek

- 13 to 15 April – discharge of sediment-laden water from a stormwater outlet on the oval site into Quarry Creek

- around 19 April – as a result of sediment-laden water being leaked, spilled, otherwise escaped or deposited from the oval into water of Quarry Creek, signs of impact were observed in waters of Quarry Creek including the presence of algae and suspended solids for over 200 metres

Council subsequently advised the EPA that the damaged pipe was plugged and a faulty joint in a stormwater pipe had been identified and repaired where sediment laden water had been seeping into Quarry Creek.

Nevertheless, the evidence of pollution led the EPA to issue a clean-up notice on 26 April to repair pollution as defined under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997.

The clean-up notice required council:

- to repair the collapsed sediment dam wall, repair the damaged section of pipe leading from the dam to the stormwater system and reinstate the holding capacity of the sediment dam;

- to assess the condition and operational status of all stormwater pipes running underneath or above at the premises to prevent any further sediment-laden water from entering the stormwater system from the premises;

- to arrange for the sediment-laden water at the premises to be lawfully disposed of and/or discharged in an appropriate fashion that does not result in further environmental harm;

- to remove the build-up of any sediment originating from the premises in Quarry Creek as well as algae and suspended solids in waters of Quarry Creek for at least but not limited to 200 m from the stormwater outlet.

Council was also required to engage an independent and suitably qualified person to review all sediment and erosion controls and identify any existing controls which are in a poor condition or ineffective. This entailed a detailed ‘Sediment and Erosion Control Plan’ for the site. Also, Council was required to engage a consultant to conduct a comprehensive inspection and assessment of the drainage systems beneath the Oval.

The project has been delayed because of the need to construct an extra retaining wall at the north-eastern corner, pump out the accumulated muddy water into trucks and repair the damaged pipes.

But the pollution has continued

Despite all these actions, in June and August there have been more incidents of sediment flowing down Quarry Creek. Some of these incidents have coincided with a rainfall event, but not all.

There is still a significant build-up of sediment along the creek even as far as Lane Cove National Park below Yanko Road. A relatively clean creek with clear water flowing over bedrock now has many pockets of sand and gravel sediment. The clean-up action has not been completed.

Council has acknowledged that the overflows at Norman Griffiths have been ongoing, and it has been working closely with contractors to address them. They advised that a significant issue, which was not immediately apparent, involved turbid water releases linked to the underground infrastructure. Action has now been taken to make the site more resilient, and the contractors are fully aware of their water management responsibilities. Council staff have said they will continue to monitor the creek, and operations staff will maintain the temporary sediment control measures until the oval works are complete.

The EPA is still considering all these incidents and may take further action.

Insights from the court case

In Issue 222 of STEP Matters we describe the case taken to the Land and Environment Court by NGANG (Natural Grass at Norman Griffiths, a group of local residents) for a judicial review of the decision to proceed with the project. The evidence presented during the case revealed shortcomings in the review of environmental factors (REF); that is the report that details the project and explains how the risks during construction and operation of the field will be managed. In this case the REF used assessments undertaken by council and the contractor.

The contractor chose to embark upon construction relying on two REF appendices that were for the installation of ‘a synthetic surface’. They were in no way based on the final design of the field as they were completed almost a decade ago – a geotechnical report (Appendix 6) and supplementary contamination investigation report (Appendix 5). Both reports highlighted the need for further investigation of the unconsolidated fill and asbestos risk. In fact, asbestos has been found during construction and buried onsite so that additional costs have been incurred.

The on-site water detention system is a major part of the project. The previous field area has acted as a stormwater detention system and there were pipes under the field taking water from the upper part of Quarry Creek across to the outlet near the swimming pool. The synthetic turf is not absorbent so the surface rainwater and water running onto the field from the surrounding slopes has to be controlled as well as Quarry Creek water from across Lofberg Road. A new system has had to be designed to allow the water to flow slowly through detention tanks and gravel beds under the surface. The large cost of this system was the reason the original plan to put synthetic turf on the oval was rejected back in 2017.

Given the shortcomings of the REF, the issues with the project were foreseeable and should have been carefully investigated before construction began. Further, the REF’s so-called ‘construction environmental management plan’ that is meant to protect the environment from harm, has already failed on more than one occasion and led to impacts on Quarry Creek, an EPA notice, and further delays.

Following the case, council has had to redesign the field and put in further mitigation measures against microplastic movement.

A clearly inadequate REF has already had major implications for ratepayers - not just adding approximately $1 million to the project that ratepayers have borne - but directly causing substantial delays to the project.

The contract stipulates an ‘external, independent review of the proposed design’ should be undertaken. Has this occurred?

Updated flood study still required

The community’s concern is that ratepayers will continue to pay the price for the REF’s inadequacies. This includes serious issues, some of which were highlighted during the court case:

- a lack of flood study modelled on the current design;

- the lack of examination of the impacts of a probable maximum flood as a result of this development as required under 171A of the Planning Act and its possible catastrophic environmental consequences.

There is also an unacceptable fire report which claims synthetic (plastic) fields are flame resistant.

A flood study on the current design is important for two reasons.

- Firstly, because previous comprehensive flood studies of a proposed synthetic field showed damage to Quarry Creek and led to the project being initially rejected in 2017.

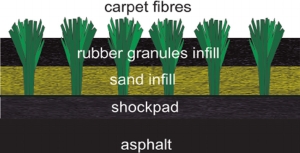

- Secondly, control measures are in place for expected rain events, but uncontrolled flooding could lead to tonnes of plastic blades fragments and cork sludge escaping from the field and polluting Quarry Creek. The synthetic turf has plastic blades that are highly buoyant and can break off as the field is played on. Cork will be used as infill to hold up the plastic grass blades to simulate natural grass. While cork is preferable to rubber tyre crumb infill (which is now banned in many countries because of toxic chemical runoff) the stability of cork infill is not proven in heavy rainfall events as has been demonstrated by the cork sludge runoff from ELS Hall field in North Ryde.

It could be that the area is never under threat from a bushfire or fire on the field, but the REF’s bushfire report is not only factually inaccurate but also completely at odds with the Chief Scientist who recommended these fields should not be placed in fire prone (or flood prone) areas. This recommendation occurred before council's decision to go ahead was made.

Questions and actions for the new council

As noted above, we would like the new council to ask questions about why ratepayers are paying for variations for the contractor hitting unconsolidated fill and asbestos given the contractor chose to rely on these completely inadequate studies to tender for the project.

We would like the new council to follow up on ecologist Roger Lembit's report that noted threats to the Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest and the orchids (some classified as endangered) around the oval due to changes to hydrology caused by the construction.

Also unknown is the whereabouts of the vulnerable microbats which were mapped at the oval, as well as the Powerful Owl which roosted in the forest above it. There was also no examination on the impact of the multiple high fences around the field given the area is a wildlife corridor.

We remain unconvinced that plastic blades and cork infill will be kept out of Quarry Creek in extreme rainfall conditions, and we will be watching this very closely. The Chief Scientist recommended that pollutant testing be carried out near synthetic fields. Council has now set up a microplastic monitoring process after intensive lobbying from the bushcare group.

The clean-up of the sediment build up needs to be completed. Council also needs to undertake the flood study of Quarry Creek to ensure is not further damaged by erosion and scouring from excess water coming off the synthetic field. Previous council flood studies clearly highlighted the risk of damage to Quarry Creek, where there is a beautifully regenerated bushcare site. We will be asking council to make any flood studies public and outline how Quarry Creek will be monitored and protected. It is not clear whether the Lane Cove Northern catchments flood study that commenced in 2022 has been completed.

It is a great shame that the local community had to raise money to get the council to assess the field adequately – it is the local community that have somewhat abated a complete flood/pollution disaster at that field. Expert witness reports by Dr Daniel Martens (flood expert) and Roger Lembit (ecologist) warning of issues were sent to council staff and councillors and the court case was only initiated when they were completely ignored. Even after the NPWS called for more time to further assess the REF, the majority of councillors rejected a motion by Councillor Kay that a consultation on the REF should be examined further. Some councillors even tried to pass a motion that NGANG should be made to pay council’s costs for the case. Sadly the experts’ concerns have proven to be justified.

Proper consultation is essential for these expensive projects

This project is a prime example of the need for councillors to take notice of expert advice and carry out transparent consultation. This can provide great insights into the impacts, good and bad of a project.

Currently the legislation does not require a council to carry out detailed consultation or an environmental impact assessment (more rigorous than a REF) on a project like Norman Griffiths Oval as it is deemed to be general maintenance. There were numerous submissions to the draft Guidelines on the Use of Synthetic Turf calling for this to be remedied.

Image: Muddy water in Quarry Creek near Yanko Road (30 June 2024)

Synthetic turf guidelines released at last, but a big disappointment

In Issue 221 we reported on the Chief Scientist’s report into Synthetic Turf Study in Public Open Spaces. One of the recommendations was a call for an accessible and reliable source of verified information that distilled the vast amount of data that is available. It also called for further research on the impact on human health from heat generated by the plastic surface and chemicals in the turf/infill and environmental impacts such as microplastic loss into waterways and the loss of habitat for local wildlife.

The government’s response was a promise to produce guidelines to assist decisions about the installation and use of synthetic turf. Nine months later they have been released but they are a huge disappointment. Submissions were invited up to 29 April so we hope for a significant rewrite.

The announcement on the Department of Planning website states that:

The guidelines will help decision-makers, planners and sports field managers who may be considering synthetic turf as an alternative to natural grass.

There are lots of lists of what to consider but little actual guidance and references to sources of information plus many important matters are missing.

Lack of information about natural turf alternative

The first issue is the lack of information about natural grass practices to enable comparison with synthetic turf. There should be information on where to find data on modern science-based techniques for soil and drainage preparation and grass choice. The guidelines say these techniques are not well known but this statement is false. There are references in the guidelines to management guidelines that was produced as long ago as 2007 but nothing about construction.

There should be a moratorium on new installations

The Chief Scientist’s report highlighted the multiple areas where further research is needed into the environmental and health impacts of synthetic turf particularly under the Australian climatic conditions. This includes the breakdown and escape into waterways of plastic blades and infill that include PFAS and microplastics. Many countries overseas that have been using synthetic turf for many years are starting to phase out its use particularly with rubber tyre crumb as infill.

Organisations like the Total Environment Centre (TEC) are calling for a moratorium on synthetic turf installations for five years until more data is available. The TEC has been working with Macquarie University on the AUSMAP: Australian Microplastic Assessment Project that is monitoring microplastic pollution in waterways.

Information missing from the guidelines

- There are many aspects of the current use of synthetic turf where the data is clear that practices should be changed. This includes the use of rubber tyre crumb as infill and the need for collection systems for microplastic runoff.

- The government has not taken action to develop standards for materials used in synthetic turf and infill, particularly imported products. There are standards in place for most other materials for public use but this essential consideration has been neglected in respect of synthetic turf.

- There are Australian standards in place for installations that impact surrounding wildlife such as the lighting systems but the draft guidelines do not mention them. The Australian government's Department of the Environment has lots of information.

- There is no clear statement of locations that are unsuitable for synthetic turf such as areas with bushfire and flooding risk and environmentally sensitive areas with nearby endangered vegetation and wildlife.

- There is little coverage of the approval process required under the planning legislation. Given all the environmental and social impacts of synthetic turf the standard for project approval should be an Environmental Impact Statement.

- There is insufficient emphasis on the need for consultation with local communities that will be affected by the installation of synthetic turf that is usually fenced off and restricts future use to specific sports so that casual recreational use is no longer possible.

- There in no mention of planning regulations requiring consultation with NPWS for developments near a national park.

- Impact on local environment from a large area of plastic that excludes wildlife (birds and insects) and amplifies the heat island effect is not covered.

Finally, the structure of the guidelines is not useful. For example, there are long explanations of how to plan the demand for sporting fields and development of council strategies that are irrelevant to the actual analysis of whether to use synthetic turf. It would more useful to have checklists of actions and considerations with references to sources of information.

Norman Griffiths Oval synthetic turf installation has become a debacle

Construction of the synthetic turf field at Norman Griffiths Oval in Bicentennial Park, West Pymble commenced in August 2023. You will recall the controversy about the use of this site for synthetic turf with its proximity to Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest and Quarry Creek, the waterway that runs under the field and flows through to Lane Cove National Park. The bushland along the creek has been transformed by bush carers working over many years.

One major issue with the choice of this location for synthetic turf is that the field acts as a stormwater detention basin. Water from rainfall events runs from the surrounding slopes into the field and into pipes and a detention system then would gradually drain ultimately into Quarry Creek at various locations. There was also a pipe running under the field taking water from the nursery on the other side of Lofberg Road into the detention system.

The installation of synthetic turf creates an area where rainwater can seep through but heavy rain will flow rapidly across the field and into Quarry Creek. Flood models were commissioned that determined that a new drainage system was required. This comprises a large area of porous aggregate which allows for vertical, filtered drainage and stormwater detention. Once the water has filtered through this detention basin it will go into a bio-retention basin where it then flows gradually into the current stormwater pipe system under the aquatic centre carpark.

There have been repeated incidents of muddy water running down Quarry Creek usually after rain since construction started. It seems the runoff from the field is not being controlled. A broken pipe is blamed so the detention system is not working. The EPA is investigating.

Now the stage of construction has been reached where there are large piles of aggregate and dirt across the site. Then there was very heavy rain on 5 and 6 April with over 200 mL. The construction site became a lake as it seems there was too much water for the drainage system (see image at the top of the page).

There have been repeated episodes of muddy water in Quarry Creek but the latest incident is the worst. A solution has to be found to pump out the water from the muddy lake. It can’t go down Quarry Creek. There is already a build-up of silt on the bed of the creek. We are trying to find out who is responsible for cleaning this up.

Meanwhile construction activity has ceased.

Muddy water flow into Quarry Creek, 150 m from oval, 6 Nov 2023

Ku-ring-gai High School hockey field

The synthetic hockey surface was installed about 30 years ago and is now worn out. The Northern Sydney and Beaches Hockey Association (NSBHA) has been working on a project to renew the surface and upgrade the players’ amenities. They originally proposed a totally new facility at Barra Brui oval in St Ives on the edge of Garigal National Park. That was eventually knocked back because car parking space was too limited. So the project is proceeding at Ku-ring-gai High.

The project is being funded through a NSW Office of Sport – Sporting infrastructure Grants ($2,720,000), NSBHA funding ($480,000) and a Ku-ring-gai Council contribution for specific carpark works ($1,000,000), giving a total of $4,200,000.

The council meeting in August voted to proceed with the joint project at Ku-ring-gai High. We cannot provide more details as all the reports presented to the meeting were confidential. The meeting minutes note that council is accepting the risks and costs associated with the project and the general manager is to be the delegated authority to execute the draft Heads of Agreement on behalf of council. What are the ‘risks and costs’? The grants are intended to cover the construction and installation costs.

Car parking is an unknown element of the project. A new parking area on the school grounds requires approval under Part IV of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, for which council would be responsible. It is hard to see how the car parking can be increased without affecting the broad area of bushland in the school grounds that abuts Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park and contains some rare plants.

The meeting minutes note that the development of the field will occur irrespective of whether development consent is obtained for the car park upgrade. In the staff report for the meeting it is stated that the project is justified because the project will lead to better containment of impacts on-site and hence reduced impact on the local community. We can’t see how impact will be reduced with more traffic on Bobbin Head Road. If the car park upgrade does not occur there will be more demand for parking on Bobbin Head Road.

Norman Griffiths court case: a loss for the community and the environment

A group of residents in West Pymble took Ku-ring-gai Council to the Land and Environment Court for a judicial review of the decision to proceed with the construction of a stormwater mitigation system and synthetic turf soccer field at Norman Griffiths Oval. A group called Natural Grass at Norman Griffiths (NGANG Ltd) was registered in order to conduct the case and receive community donations.

This follows council’s decision to proceed with the project in early March 2023 after the release of the Review of Environmental Factors (REF), version 8, two weeks earlier. The haste in starting work was a cause of much frustration in the community and a fiery public forum meeting. After all we had had to wait over 14 months to see the details of the design and the REF. The time available to review the REF was inadequate; much shorter than promised. The councillors dismissed the relevance of the environmental issues raised by the community on the grounds that the REF provided assurance that the issues were not significant.

An injunction was accepted by the court to stop construction past the stormwater mitigation system stage until the case was decided. The case was expedited so there would not be a long delay before contractors started laying the turf.

Over $120,000 was raised towards the costs of the case and expert witnesses. This is a demonstration of the high level of public interest and concern about the use of synthetic turf.

The gross pollution trap and diversion to underground detention ... but what about the water flow from the hill above the field?

Last minute amendment to the REF

NGANG was right! The time allowed to review the REF was too short. The REF was missing some of the analysis required about environmental impacts following an amendment to the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act). Council decided it was okay to make a last minute amendments so version 9 was published on

4 July. Sadly, the L&E Court did not see that this expediency was an issue that could prevent the project proceeding but it is another demonstration of council’s poor governance.

Court case begins on 2 August

The main arguments submitted by NGANG were that:

Not all required environmental issues were considered to the fullest possible extent

The case was a judicial review where the relevant task is the consideration of the decision made by council. The judgement explained that a challenge may be made on the basis that the decision-maker should, acting reasonably, have made some additional inquiries. Expert evidence as to what the outcome of those inquiries would have been is, in some cases, admissible. Expert evidence was provided by Dr Scott Wilson, a microplastics expert and Dr Martens, a stormwater expert. Council also engaged three experts on flooding, pollution and ecology.

NGANG argued that council had not examined and taken into account to the fullest extent reasonably possible all matters likely to affect the environment following the installation of the synthetic turf. This is a duty imposed under section 5.5 of the EP&A Act.

NGANG’s case was that there should have been inquiries covering:

- a pollutant load study to assess microplastic pollution;

- a flood study to understand the flood impacts on the area and whether the stormwater detention proposed would function in the manner intended; and

- an investigation and understanding of where the overland stormwater flow path would be located in circumstances of an extreme rainfall (1 in 100 year event); and the investigation of the impact of the overland flow path upon the Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest below the field.

There was disagreement between NGANG’s expert and council as to the adequacy pf the onsite stormwater detention system (OSD). As an observer of the case, it appeared that much of the discussion of the OSD was at cross-purposes in referring to the existing system versus the new system. A new system had to be installed because the hard surface of the synthetic turf could not retain the stormwater. The old grass surface acted as the OSD.

The court ruled that the judicial review could not consider the merits of council’s decision and could only review whether it was acting reasonably. The judge rejected the evidence of Dr Martens and Dr Wilson that was sought to be tendered to establish the duty to make further inquiries in the circumstances of this case.

Stormwater system

Dr Martens advised on the requirement to undertake a study to understand the flood impacts on the area and whether the stormwater detention proposed would function in the manner intended. The report in the REF by Optimal Stormwater Ltd determined that the proposed system was capable of operating in the manner and to the specifications for which it was designed. The judge ruled that, in the circumstances, there was nothing on its face that would cause a decision-maker to consider that the opinions expressed were not reliable or not properly formed. The suggestion that the council was not entitled to take ‘at face value’ the information in the Optimal Report has no foundation. The question remains as to whether the specifications are adequate.

Microplastics

The ruling in relation to this issue indicates that the wrong question was being asked. On the evidence contained in the REF there is a goal of minimising microplastic loss from the synthetic field and identifies the measures to be adopted to achieve such goal. It is acknowledged that 100% capture is not possible, especially in extreme rainfall events but no further inquiries were recommended.

There is an obligation to commission an environmental impact statement

The other main ground argued by NGANG was the failure to comply with section 5.7(1) of the EP&A Act. This provision contains within it two obligations, first to determine whether the activity has a significant effect on the environment and secondly, if so, to not carry out the activity or grant an approval until it has obtained and considered an environmental impact statement (EIS):

In submissions NGANG formulated this ground on three bases:

- If the court found on the evidence that there was a prospect that the flood mitigation scheme being an integral part of the activity did not work as asserted by the manufacturer, either in not acting as an OSD system or not sufficiently capturing the overland flows, the court would find, on the evidence, that the proposal was likely to significantly affect the environment.

- If the court found on the evidence that the OSD system would not work as designed the infill and microplastics will not be sufficiently captured or retained on-site and will be washed down into the receiving environment, including Quarry Creek.

- A separate impact which has not been assessed from the overland flow path, which is the water diverting to the south over the field and then discharging into Quarry Creek, and the potential impacts on the adjoining STIF and Quarry Creek from that overland flow.

The judgement stated that consideration of significant impact on the environment is so broad and far reaching that it was unlikely to be determined as an objective fact by the court in judicial review proceedings. Therefore the question of whether an activity is likely to significantly affect the environment is not an objective jurisdictional fact but is a matter for the determining authority (the council) to determine acting reasonably. It seems that the precautionary principle doesn’t have any weight in this case whereby uncertainty does not justify inaction.

In this case the Judge found that council had acted reasonably. Statements by Dr Martens that the impacts may occur were insufficient to permit a finding of a likely significant effect on the environment. Modelling of changes in the hydraulic performance had not been done to enable the Court to make its own assessment.

Full steam ahead but what will happen when the plastic grass needs to be replaced?

So sadly, the construction of the synthetic turf field is now proceeding at maximum pace with completion possible by the end of this year.

The synthetic surface will not last forever, the lifetime with normal levels of use is 8 to 10 years. The question is, will council be able to replace the surface with synthetic turf? Now that a stormwater mitigation system is in place the flood risk from the field that acted as a stormwater detention basin has been substantially ameliorated. So it would be an excellent base for a natural grass field.

Currently there is no effective system for recycling the materials in synthetic turf so the large volume of material ends up in landfill. The evidence of environmental harm from the use of synthetic turf overseas is growing as is community opposition to its use because of the heat and injury risks. Several states in the USA have banned future installations of artificial turf because it contains dangerous chemicals such as PFAS compounds.

The Chief Scientist’s review into the design, use and impacts of synthetic turf in public open spaces highlighted the need for more research into human health and environmental impacts. Microplastics are a becoming more and more pervasive in our waterways. They can also interact with soil fauna, affecting their health and soil functions. Synthetic turf breaks down with people running over it and general deterioration from sunlight exposure. This breakdown increases as the turf blades age. The Norman Griffiths REF acknowledges that it is not possible to capture all the microplastics that will break off the turf. They will be washed off the field by rain but also blown away by wind due their small size of less than 5 mm.

We understand that council will be testing Quarry Creek for microplastics but the soil within the STIF forest and bushland below the field should also be tested.

The outcome of the chemical analysis must be taken into account when the replacement of the field surface is considered. Also we hope that the guidelines developed from the Chief Scientist’s review will provide meaningful decision making processes.

Ultimately the question that has to be asked is about the appropriateness of adding a large area of plastic to the environment when there is a viable natural alternative; that is real grass!

There has been such strong community opposition to synthetic turf at Norman Griffiths and in other parts of Sydney it will be difficult for councils to ignore in making future decisions.

Chief Scientist’s report finally released – there should be a moratorium on new synthetic fields

The Chief Scientist’s report, Synthetic Turf Study in Public Open Spaces has finally been released but fails to give definitive guidance.

Main conclusion is wrong – we cannot treat synthetic turf as an experiment!

The report developed a set of recommendations that it states will (p vii):

allow NSW to adopt an accelerated ‘learn and adapt’ approach to the use of synthetic turf under NSW conditions … If applied, they will allow NSW to set the scene over the next decade, using new fields as a testbed to contribute to innovation and data-driven decisions.

This statement is totally at odds with the precautionary principle. New synthetic fields should not be approved if the major issues cannot be addressed.

The Natural Turf Alliance is calling for the NSW government to put a stop to all plans for synthetic turf on playing fields until there is sufficient information to enable more evidence-based decision making processes. It is only right to take a precautionary approach to ensure that there are no regrettable long-term impacts on human health and the environment. Also, many of the highlighted issues could have significant financial consequences.

In the meantime, there is an urgent need to upgrade some playing fields, and natural turf can be used. Councils are already managing hundreds of natural grass fields. There are ways of doing a better job of upgrading and maintaining these fields. The report acknowledges this but then says nothing more.

Background

There has been considerable community concern about the installation of synthetic turf on playing fields, particularly in environmentally sensitive locations, and bad experiences with the planning process. Following a public enquiry in early 2021 that amplified these issues, in November 2021, Rob Stokes (then) Minister for Planning and Public Spaces, asked the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer to provide an independent review into the design, use and impacts of synthetic turf in public open spaces.

It was promised in mid-2022. It took the Greens to issue a standing order in the Legislative Council for it to be finally released on 9 June 2023. The report was dated 13 October 2022. Who was trying to hide the results? Was it the Minister for Planning, Anthony Roberts whose desk it was sitting on? The excuse given was it that was ‘cabinet-in-confidence’ and consultation was taking place with councils and sporting bodies about the guidelines that should be issued for synthetic turf installations. In the meantime lots of decisions are being made without this information.

What the report says about natural turf

The first item of the terms of reference is:

- Identify, describe and provide advice on:

(a) key scientific and technical issues associated with the use of synthetic turf compared with grass surfaces in public spaces

The report states (p v.):

Best practice guidelines for improving the performance of natural turf have been developed in NSW. If applied to installation and ongoing management of natural turf sporting fields, these practices may allow increased performance of natural turf fields to meet demand.

In the more detailed discussion of the recommendations, in reference to an example of the guidelines developed for the Lower Hunter, the report states that analysis in the guidelines reported:

that when lifecycle costs and carrying capacity were considered, natural turf fields built to best practice were more cost effective than alternative options including synthetic turf.

Nowhere in the report is there a comparison of the scientific and technical issues that apply to the use of natural grass and synthetic turf. It is frustrating that there is no discussion about making a choice between the two. They are treated as separate entities.

Natural turf is already proven to be a better option

At the community forum organised by the Natural Turf Alliance on 23 June the speakers demonstrated that natural turf will be successful in terms of available playing hours if the correct soil preparation and drainage system is applied. Councils just have to improve their practices.

Demand for synthetic turf

According to the report, which is at least a year out of date, there are currently about 181 synthetic turf fields in NSW in public and private (eg schools) spaces. This compares with about 30 in 2018. The support for these installations has been driven by the soccer associations that are arguing that available playing hours are too restricted on grass fields to meet demand. This has been the case in the past couple of years that were abnormally wet.

Demand is increasing with population growth and it is argued by the soccer associations that the game is becoming more popular as women are taking up the game.

There are other arguments about several issues such as relative life cycle cost and water use that still being debated.

The concerns about use of synthetic turf

The report describes many issues with the use of synthetic turf and many where more research is required.

Chemical composition

Many synthetic sports fields in NSW feature long synthetic blades supported by infill, the most commonly used infill is styrene butadiene rubber crumb sourced from recycled tyres. The crumb is imported and there is a lack of information about potential contaminants such as heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Currently, there is insufficient information and a lack of standards about the materials and chemical composition of synthetic turf. Other types of infill such as cork, are being used in newer fields but the review does not provide detail about these.

Longevity of synthetic fields

Overall, it is not clear how Australian climatic conditions will affect expectations about the longevity and carrying capacity of synthetic fields compared with overseas experience that is the basis of current decision making about installation and cost-benefit considerations.

Sustainability

Practices and standards for recycling and disposal are changing locally and overseas. Australia banned the export of waste tyres including tyre crumb from January 2022 so this component of synthetic turf has to be recycled locally or sent to landfill. The process of separating turf into components that are reusable is highly complex. Plans for a recycling facility near Albury have not yet been established.

Health

Heat impacts are a priority area for research. The commissioned reports and literature review did not identify major health risks associated with the use of synthetic turf, although it was noted that significant knowledge gaps remain and research should prioritise the potential health impacts of chemicals such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and some heavy metals. The health impacts of the high heat levels of synthetic turf are not discussed in detail but the closure of fields in hot weather is canvassed especially for younger children.

The report notes that per- and poly-fluoroalkyl compounds have been found in low concentrations in the turf blades and base carpet. They create a risk of cumulative harm to aquatic and soil life, the environment and ultimately human health.

Social and wellbeing effects

Important considerations for planners and councils will vary with each site and include reduction in community access, odours from synthetic materials and increased artificial light.

Environment

Many potential impacts are raised that need to be mitigated. Microplastics and infill have entered waterways. Design guidelines are now in force to control leakage but their success still needs to be monitored. Older fields have been observed to lose a lot of rubber crumb especially as they age. The impact of escaping infill and turf fibre (microplastics) on local soil and ecology needs to be researched.

Fragmentation of animal habitat and disruption of ecological functions will occur through the loss of natural grass, increase in heat and additional light at night. The report states that synthetic turf is unsuitable for locations with flood and bushfire risk or in sensitive ecological locations.

Recommendations

Community groups concerned about the increasing use of synthetic turf have highlighted several issues. Many of these are the subject of recommendations in the report.

1. Planning approval process

In most cases a development approval process is not required from the local council. The assessment required is a Review of Environmental Factors (REF) subject to requirements defined in the Environmental Planning and Assessment Regulations.

The report looked at a sample of REFs and found many gaps in coverage of these requirements, for example:

- climate change impacts on surface heat and stormwater

- impact of impermeable surface on soil health

- waste disposal at the end of life of the turf

- micro and nano-plastic contamination

- impact of increased light and heat on fauna outside the footprint of the field

The approval process does not provide clear requirements for community consultation. The report highlights this gap in the process:

Early community engagement that continues through the planning period enables discussion and representation of all stakeholders.

Consultation was sadly lacking in the case of Norman Griffiths.

2. Mitigating environmental risk

A plan is needed for the development of appropriate standards for best practice installation and use, consistency with net zero targets and end-of-life solutions via industry engagement with government and researchers.

In addition, fields in proximity to sensitive ecosystems should be independently assessed to assist with management of identified environmental issues. Risk assessments should be undertaken so that synthetic fields are not approved in areas of high environmental risk including bushfire prone areas or those with higher likelihood of flooding.

3. Future data and research

The report recognises that the scale of public investment in sporting infrastructure requires a more systematic and data-driven approach to decision-making. There is a vast amount of existing information from different sources about the design, management and performance of sporting fields, but these are not readily available or collated. A more accessible and reliable source of verified information is required.

Data collection should be complemented by the research program to address key knowledge gaps in human health and environmental impacts. A key research priority is understanding the characteristics and composition, including the chemical composition, of materials used in synthetic turf and associated layers.

Norman Griffiths synthetic turf – bad PR by Ku-ring-gai Council again!

At the time of finalising an article for our last issue of STEP Matters we were still waiting for the review of environment factors (REF) for council’s project to install synthetic turf at Norman Griffiths Oval in West Pymble. This was to be the major document giving details of the stormwater mitigation works and the design specifications of the field together with the management of identified environmental risks. The details of the design had not been made available previously.

By the time this happened on 27 February there was suddenly a great urgency to get started on the project. The public was given only two weeks to review the 72 page document plus 15 appendices and seek answers to questions. The bulldozers were due to start work on 13 March.

The local stakeholder groups wanting details about the project had been told that they would have four to six weeks to review the REF. So there were many representations made demanding that there should be more time. After all, the mayor had signed the documents giving the go ahead in November 2021 while the council was in caretaker mode before the election. Council had taken 15 months to produce the report so why the rush? Was it something to do with a time limit on the payment of grants of about $1 million promised by the NSW government?

Council decided to hold an Extraordinary General Meeting to discuss the project and provided for a further opportunity for submissions at a public forum on 14 March. Council was not swayed by the arguments that more time had been granted even though we had written evidence of this commitment.

The Extraordinary General Meeting was a farce. They simply presented a resolution that the REF be noted and received. The issues raised at the public forum were treated as unimportant.

One issue was the lack of consultation with NPWS that is required as runoff from the field will end up in Lane Cove National Park via Quarry Creek. NPWS was given the same short period to review the REF. The only commitment by council with NPWS is for continuing consultation in relation to any issues that may emerge.

This is just another example of the disregard council staff have for community concerns. Similar attitudes were experienced with the St Ives Showground Plan of Management where consultation occurred after decisions had already been made.

Once the field is in use and the tonnes of cork infill are in place, the amount of infill migration off the field with regular use or heavy rain will be a watched closely. Water quality is being regularly monitored via the Streamwatch program.

The picture at the top of the page shows Norman Griffiths Oval on 15 April 2023.

Norman Griffiths synthetic turf

We are still waiting for the review of environment factors for Ku-ring-gai Council’s project to install synthetic turf at Norman Griffiths Oval in West Pymble. See STEP Matters Issue 217 for more background. It is over a year now since council decided to proceed with the project.

We understand that council is waiting for the Chief Scientist’s report on guidelines for the use of synthetic turf to be released. That, we understand, was completed in August and is still sitting on the planning minister’s desk, probably until after the election. What has he got to hide?

On the subject of synthetic turf, the Natural Turf Alliance has a new website with lots of information about synthetic turf and the alternative of natural grass.

The Natural Turf Alliance is a registered association consisting of community groups, including STEP, committed to preserving and developing natural grass open spaces including sporting fields.

Frustration over lack of information about the Norman Griffiths Oval synthetic turf project

While Ku-ring-gai Council was in caretaker mode in December 2021, Mayor Cedric Spencer signed the documents giving the go-ahead for the project to install synthetic turf at Norman Griffiths Oval in West Pymble. This was despite the considerable community opposition and the fact that a Review of Environmental Factors (REF) had not been completed. The opponents were assured that the project would not go ahead if the REF proved that the impacts could not be satisfactorily managed. We have already written about our concerns with this project.

The main concerns relate to chemical pollution and cork infill run-off from the field into Quarry Creek that runs into Lane Cove National Park and changes in hydrology that could danger the surrounding Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest vegetation.

There is considerable frustration about the lack of information about progress over the past 9 months in the design of the project and the analysis of environmental impacts. It appears that members of the West Pymble Soccer Association have been privy to information provided in meetings with council staff. STEP and the local bushcare volunteers were promised that a community reference group would be set up to inform them about the project as well as the soccer club.

This situation has led to one of the volunteer bushcarers, Bronwen Hanna, resigning as convenor of the Quarry Creek group. Here is her letter.

Re: Resignation as KMC Coordinator: Quarry Creek and Little Yanko Bushcare Sites

It is with great regret that I inform you of my decision to resign as Ku-ring-gai Council’s Bushcare Co-ordinator for Quarry Creek and Little Yanko sites. Given the hours of effort that myself and other volunteers have put into the site, I am disappointed in the way that council staff have treated our attempts to ensure the site continues to flourish.

Firstly, KMC staff have declined all requests to meet and discuss questions around mitigation strategies which would allay concerns about impacts of a synthetic field upstream which have recently raised by the NSW Chief Scientist. What has made this more difficult for me is it appears that West Pymble soccer club and the NSSA – who potentially stand to gain financially from this development through reduced soccer fees – have been furnished with information that should also be made available to our group as affected stakeholders.

It may be that council’s plans will mitigate any impacts that have occurred in other projects. If this is the case, I find it hard to comprehend why staff would not be happy to meet with volunteers with valid concerns. Unfortunately, volunteers have been forced to seek information through GIPA requests – requests that have taken up a great deal of time. We have had to pay for information which I believe should be freely available to residents who are working for the public interest.

Secondly, council appears to have rejected our requests for independent expert monitoring of Quarry Creek before and after the field’s construction (which we asked for in our original submission on the project). This is hard to understand given previous substantial investment through grants funding and rehabilitating the creek through rain gardens, vegetated swales and Lofberg Oval stormwater harvesting, as is the rationale that council cannot afford to undertake water/microplastic monitoring given council is spending $3.6m on the project.

I note also that council have not responded to NSW National Parks concerns about the project, nor abided by its own resolution to keep National Parks informed about the project as it progressed.