Displaying items by tag: extinction

Report card on our biodiversity

Australia is losing more biodiversity than any other developed nation. Already this year the charismatic and once abundant gang gang cockatoo has been added to our national threatened species list, the koala has been listed as endangered and the Great Barrier Reef suffered another mass bleaching event.

The Australian public consistently rates the loss of our unique plants and animals as a key concern. Indeed, in a recent poll of 10,000 readers of The Conversation, 'the environment' was identified as the second-biggest issue affecting their lives, behind climate change at number one.

The Coalition has been in government since 2013. So what has it done about the biodiversity crisis? Unfortunately, the state of Australia’s plants, animals and ecological communities suggests the answer is - not nearly enough.

In fact, as the extinction crisis has escalated, protection and recovery for threatened species has declined. Poor decisions are contributing to the problem, rather than solving it.

The sorry state of Australia’s biodiversity

Australia has formally acknowledged the extinction of 104 native species since European colonisation, but the true number is likely much higher.

Threatened bird, mammal and plant populations have, on average, halved or worse since 1985. Species recently thought to be safe – such as the bogong moth, gang gang cockatoos, and even the iconic koala – are being added to the global and national threatened species lists following drought, catastrophic fires and habitat destruction.

Today, 19 ecosystems show clear signs of collapse. This includes the Great Barrier Reef, savannas, mangroves, tropical rainforests, and tall mountain ash forests. These losses have profound ramifications for clean air and water, productive agriculture, pollination, and well-being.

Biodiversity is a crucial part of Australia’s national identity and Aboriginal culture. It delivers billions of dollars in tourism revenue and underpins most sectors of our economy.

It’s important for our health, too. COVID lockdowns recently brought the critical role of nature to our well-being into sharp focus, with thriving biodiversity shown to deliver avoided costs to the healthcare system.

Ignoring key recommendations

A 2018 Senate inquiry into the extinction crisis of Australian animals (fauna) concluded that native fauna was declining. It found biodiversity protection was under-resourced and failing, and Australia urgently needs an independent environmental regulator.

In 2022, the federal Auditor-General reviewed the government’s implementation of Australia’s threatened species legislation, finding:

limited evidence that desired outcomes are being achieved, due to the department’s lack of monitoring, reporting and support for the implementation of conservation advice, recovery plans.

The national Threatened Species Strategy focuses on 100 species and a few iconic places. But more than 1,800 species and ecosystems are threatened with extinction.

And economic analyses indicate we currently spend about around 7% of the targeted A$1.6 billion per year required to halt species loss and recover nationally listed threatened species.

These findings were reinforced in 2020 by a major independent review of Australia’s environment law – Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

The review by Professor Graeme Samuel made 38 recommendations, but almost none have been implemented. They include establishing an Environment Assurance Commissioner, rigorous national environmental standards and resourcing compliance and enforcement of environmental regulations.

Failure to protect what we have

Land clearing is a key threat to Australian wildlife, yet the government has not made meaningful progress to halt it.

The hectares cleared in New South Wales over the last decade have tripled, and a staggering 2.5 million hectares have been cleared in Queensland between 2000 and 2018.

Worryingly, more than 7.7 million hectares of threatened species habitat have been cleared since the EPBC Act came into force (between 2000 and 2017), including 1 million hectares of koala habitat.

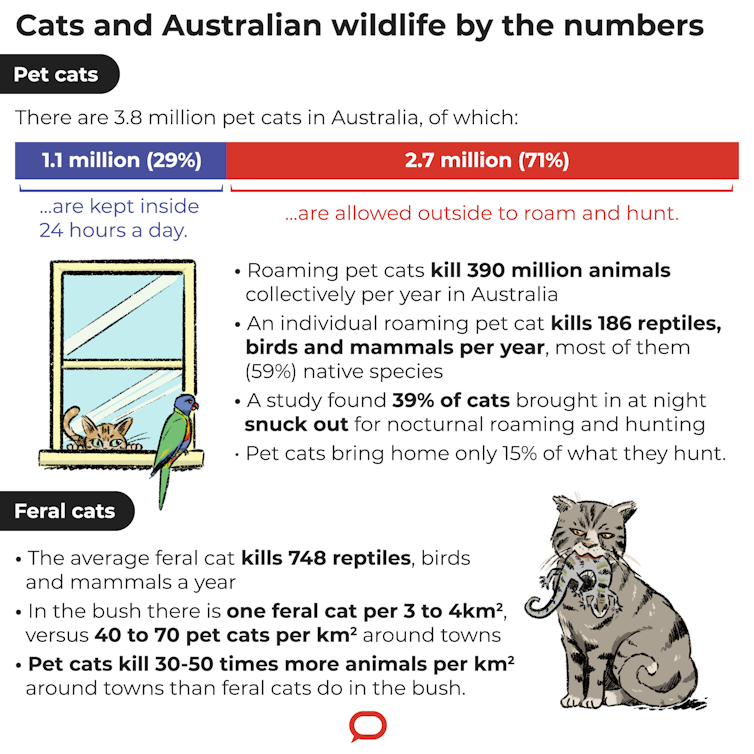

Invasive species – such as cats, foxes, rabbits, deer and buffel grass – continue to wreak havoc on many of our most endangered species.

Cats alone kill 1.7 billion native animals each year and threaten at least 120 species with extinction. While feral predator control has received some focus, the effort still falls well short of what’s required.

Lack of transparency and accountability

Official reviews have consistently found the federal government’s approach to protecting biodiversity lacks transparency and accountability.

Questions have also been raised about the federal government’s delay in releasing its five-yearly State of the Environment Report ahead of the election.

And investigations have raised serious concerns about how the government handled decisions regarding grasslands illegally destroyed by a company part-owned by a government minister.

A key advisor to the government recently labelled a major scheme to promote forest restoration as carbon credits as environmental and taxpayer 'fraud'.

A federal integrity commission, if it existed, could have explored these cases.

The government also continues to back activities that cause damage to biodiversity, including the fossil fuel and forestry industries.

On agriculture, the government is pursuing a 'biodiversity stewardship' policy, to financially reward farmers for protecting wildlife.

But ongoing approval of unsustainable land management practices, particularly land clearing (of which agriculture is responsible for the lion’s share) will likely overshadow any stewardship gains.

So what’s needed to prevent future extinctions?

Labor has not yet revealed its full suite of environment policies. This week it told Guardian Australia it will release more details before the election, and has called on the government to release the State of the Environment report.

So what policies are needed to reverse the biodiversity crisis? The answer is: spend more and destroy less.

Just two days of Coalition election promises (estimated at $833 million per day) would fund recovery for Australia’s entire list of threatened species for a year.

Systems for protecting biodiversity need stronger legal mandates and less discretion for ministers to override decisions about project approvals, species listing and other matters.

Biodiversity should be integrated into key aspects of government practice. For example, it makes no sense to invest in protecting koalas while simultaneously approving koala habitat clearing.

And we need investment in every threatened species, not just a hand-picked few.

Finally, transformative policies are needed to support the substantial opportunities to enhance and restore biodiversity. This includes:

- using nature to help mitigate climate change

- green recovery of the economy post-COVID

- finding ways to farm profitably while enhancing biodiversity

- designing cities where people and nature can both flourish.

The fate of nature underpins our economy and health. Yet in the election campaign to date, there’s been a deafening silence about it. ![]()

Sarah Bekessy, Professor in Sustainability and Urban Planning, Leader, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University and Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Ecology, School of Ecosystem and Forest Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sad Story at the Federal Level

The ABC reported that the May budget has reduced the budget allocation of funding to the biodiversity and conservation division of the Department of Environment and Energy by 25%. As a result the number of jobs will be cut by the full time equivalent of 60 (25% of the total) in the crucial area of threatened species monitoring. The Australian Conservation Fund has found that this department’s budget had been cut by about 60% in the forward estimates since the Coalition won government.

The only new spending on the environment in this year’s budget is the one off $444 million payment to support the Great Barrier Reef 2050 Partnership Program.

The biodiversity and conservation division coordinates the listings of threatened species and their recovery plans, devises Australia's national biodiversity strategy, and coordinates action around the country against invasive species and other biosecurity threats.

Researchers at the Threatened Species Recovery Hub in the Australian government's National Environmental Science Program found about a third of Australia's threatened species and 70% of its threatened ecological communities were not being monitored at all.

The staff reductions could delay threatened species being listed and having recovery plans implemented. Experts have said that it is highly likely species will become extinct and no one will notice.

Australia already has a world beating record of species extinction, which has seen it lose at least 30 mammals and 29 birds since colonisation – the highest mammalian extinction rate in the world. The budget cuts can only make this situation worse.

Senate Inquiry into Faunal Extinctions

The serious situation of species extinctions has been recognised by the Senate. An inquiry is being carried out by the Environment and Communications and References Committee into the ‘faunal extinction crisis’. Its official description is:

An inquiry into Australia's Faunal extinction crisis including the wider ecological impact of faunal extinction, the adequacy of Commonwealth environment laws, the adequacy of existing monitoring practices, assessment process and compliance mechanisms for enforcing Commonwealth environmental law, and a range of other matters.

Click here for more details and to make a submission. Submissions may be made up to 10 September and the committee is due to complete their report by 3 December 2018.

There is already a public consultation process underway for updating Australia’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy – see STEP Matters issue 194. Submissions closed in March. The submissions on the website (282 in all) roundly condemn the draft new strategy. For example here is what the Threatened Species Scientific Committee has to say:

Overall the committee found the revised plan to be extremely disappointing. In particular, it lacks substance on how Australia will address its international commitments and it fails to provide the direction needed to guide national activities over the coming decade. If Australia’s strategy is to achieve its objectives, and to maintain Australia’s reputation as a global leader in biodiversity conservation, a fresh approach that explicitly lays out a plan with national leadership for real action is needed in the next iteration of the strategy.

The Senate inquiry is taking on a big task that we hope will have the authority to overcome the inadequacies of the process being undertaken by the Department of Environment and Energy.