Displaying items by tag: magpies

Altruism in birds? Magpies have outwitted scientists by helping each other remove tracking devices

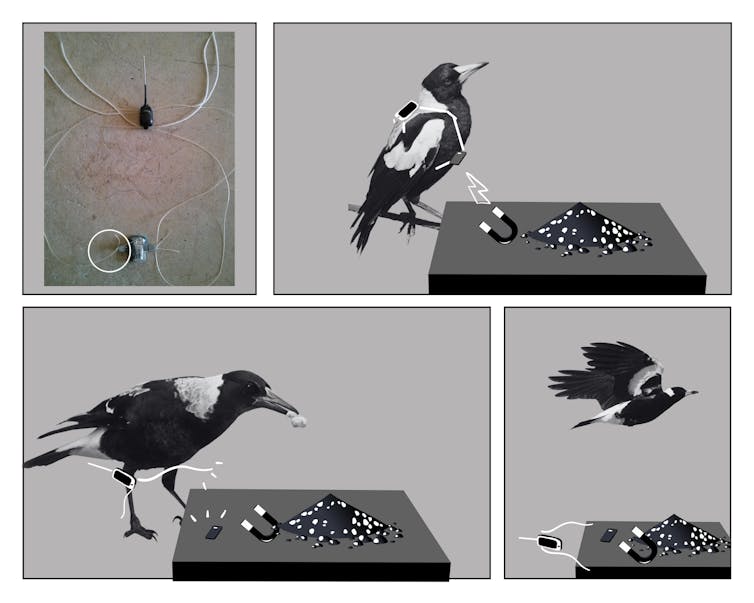

When we attached tiny, backpack-like tracking devices to five Australian magpies for a pilot study, we didn’t expect to discover an entirely new social behaviour rarely seen in birds.

Our goal was to learn more about the movement and social dynamics of these highly intelligent birds, and to test these new, durable and reusable devices. Instead, the birds outsmarted us.

As our new research paper explains, the magpies began showing evidence of cooperative “rescue” behaviour to help each other remove the tracker.

While we’re familiar with magpies being intelligent and social creatures, this was the first instance we knew of that showed this type of seemingly altruistic behaviour: helping another member of the group without getting an immediate, tangible reward.

Testing exciting new devices

As academic scientists, we’re accustomed to experiments going awry in one way or another. Expired substances, failing equipment, contaminated samples, an unplanned power outage – these can all set back months (or even years) of carefully planned research.

For those of us who study animals, and especially behaviour, unpredictability is part of the job description. This is the reason we often require pilot studies.

Our pilot study was one of the first of its kind – most trackers are too big to fit on medium to small birds, and those that do tend to have very limited capacity for data storage or battery life. They also tend to be single-use only.

A novel aspect of our research was the design of the harness that held the tracker. We devised a method that didn’t require birds to be caught again to download precious data or reuse the small devices.

We trained a group of local magpies to come to an outdoor, ground feeding “station” that could either wirelessly charge the battery of the tracker, download data, or release the tracker and harness by using a magnet.

The harness was tough, with only one weak point where the magnet could function. To remove the harness, one needed that magnet, or some really good scissors. We were excited by the design, as it opened up many possibilities for efficiency and enabled a lot of data to be collected.

We wanted to see if the new design would work as planned, and discover what kind of data we could gather. How far did magpies go? Did they have patterns or schedules throughout the day in terms of movement, and socialising? How did age, sex or dominance rank affect their activities?

All this could be uncovered using the tiny trackers – weighing less than one gram – we successfully fitted five of the magpies with. All we had to do was wait, and watch, and then lure the birds back to the station to gather the valuable data.

It was not to be

Many animals that live in societies cooperate with one another to ensure the health, safety and survival of the group. In fact, cognitive ability and social cooperation has been found to correlate. Animals living in larger groups tend to have an increased capacity for problem solving, such as hyenas, spotted wrasse, and house sparrows.

Australian magpies are no exception. As a generalist species that excels in problem solving, it has adapted well to the extreme changes to their habitat from humans.

Australian magpies generally live in social groups of between two and 12 individuals, cooperatively occupying and defending their territory through song choruses and aggressive behaviours (such as swooping). These birds also breed cooperatively, with older siblings helping to raise young.

During our pilot study, we found out how quickly magpies team up to solve a group problem. Within ten minutes of fitting the final tracker, we witnessed an adult female without a tracker working with her bill to try and remove the harness off of a younger bird.

Within hours, most of the other trackers had been removed. By day 3, even the dominant male of the group had its tracker successfully dismantled.

We don’t know if it was the same individual helping each other or if they shared duties, but we had never read about any other bird cooperating in this way to remove tracking devices.

The birds needed to problem solve, possibly testing at pulling and snipping at different sections of the harness with their bill. They also needed to willingly help other individuals, and accept help.

The only other similar example of this type of behaviour we could find in the literature was that of Seychelles warblers helping release others in their social group from sticky Pisonia seed clusters. This is a very rare behaviour termed 'rescuing'.

Saving magpies

So far, most bird species that have been tracked haven’t necessarily been very social or considered to be cognitive problem solvers, such as waterfowl and raptors. We never considered the magpies may perceive the tracker as some kind of parasite that requires removal.

Tracking magpies is crucial for conservation efforts, as these birds are vulnerable to the increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves under climate change.

In a study published this week, Perth researchers showed the survival rate of magpie chicks in heatwaves can be as low as 10%.

Importantly, they also found that higher temperatures resulted in lower cognitive performance for tasks such as foraging. This might mean cooperative behaviours become even more important in a continuously warming climate.

Just like magpies, we scientists are always learning to problem solve. Now we need to go back to the drawing board to find ways of collecting more vital behavioural data to help magpies survive in a changing world. ![]()

Dominique Potvin, Senior Lecturer in Animal Ecology, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Magpies can Form Friendships with People – Here's How

Can one form a friendship with a magpie – even when adult males are protecting their nests during the swooping season? The short answer is: 'Yes, one can' - although science has just begun to provide feasible explanations for friendship in animals, let alone for cross-species friendships between humans and wild birds.

Ravens and magpies are known to form powerful allegiances among themselves. In fact, Australia is thought to be a hotspot for cooperative behaviour in birds worldwide. They like to stick together with family and mates, in the good Australian way.

Of course, many bird species may readily come to a feeding table and become tame enough to take food from our hand, but this isn’t really 'friendship'. However, there is evidence that, remarkably, free-living magpies can forge lasting relationships with people, even without depending on us for food or shelter.

When magpies are permanently ensconced on human property, they are also far less likely to swoop the people who live there. Over 80% of all successfully breeding magpies live near human houses, which means the vast majority of people, in fact, never get swooped. And since magpies can live between 25 and 30 years and are territorial, they can develop lifelong friendships with humans. This bond can extend to trusting certain people around their offspring.

A key reason why friendships with magpies are possible is that we now know that magpies are able to recognise and remember individual human faces for many years. They can learn which nearby humans do not constitute a risk. They will remember someone who was good to them; equally, they remember negative encounters.

Why become friends?

Magpies that actively form friendships with people make this investment (from their point of view) for good reason. Properties suitable for magpies are hard to come by and the competition is fierce. Most magpies will not secure a territory – let alone breed – until they are at least five years old. In fact, only about 14% of adult magpies ever succeed in breeding. And based on extensive magpie population research conducted by R. Carrick in the 1970s, even if they breed successfully every single year, they may successfully raise only seven to eleven chicks to adulthood and breeding in a lifetime. There is a lot at stake with every magpie clutch.

Read more: Bird-brained and brilliant: Australia’s avians are smarter than you think

The difference between simply not swooping someone and a real friendship manifests in several ways. When magpies have formed an attachment they will often show their trust, for example, by formally introducing their offspring. They may allow their chicks to play near people, not fly away when a resident human is approaching, and actually approach or roost near a human.

In rare cases, they may even join in human activity. For example, magpies have helped me garden by walking in parallel to my weeding activity and displacing soil as I did. One magpie always perched on my kitchen window sill, looking in and watching my every move.

On one extraordinary occasion, an adult female magpie gingerly entered my house on foot, and hopped over to my desk where I was sitting. She watched me type on the keyboard and even looked at the screen. I had to get up to take a phone call and when I returned, the magpie had taken up a position at my keyboard, pecked the keys gently and then looked at the 'results' on screen.

The bird was curious about everything I did. She also wanted to play with me and found my shoelaces particularly attractive, pulling them and then running away a little only to return for another go.

Importantly, it was the bird (not hand-raised but a free-living adult female) that had begun to take the initiative and had chosen to socially interact and such behaviour, as research has shown particularly in primates, is affiliative and part of the basis of social bonds and friendships.

Risky business

If magpies can be so good with humans how can one explain their swooping at people (even if it is only for a few weeks in the year)? It’s worth bearing in mind that swooping magpies (invariably males on guard duty) do not act in aggression or anger but as nest defenders. The strategy they choose is based on risk assessment.

A risk is posed by someone who is unknown and was not present at the time of nest building, which unfortunately is often the case in public places and parks. That person is then classified as a territorial intruder and thus a potential risk to its brood. At this point the male guarding the brooding female is obliged to perform a warning swoop, literally asking a person to step away from the nest area.

If warnings are ignored, the adult male may try to conduct a near contact swoop aimed at the head (the magpie can break its own neck if it makes contact, so it is a strategy of last resort only). Magpie swooping is generally a defensive action taken when someone unknown approaches who the magpie believes intends harm. It is not an arbitrary attack.

When I was swooped for the first time in a public place I slowly walked over to the other side of the road. Importantly, I allowed the male to study my face and appearance from a safe distance so he could remember me in future, a useful strategy since we now know that magpies remember human faces. Taking a piece of mince or taking a wide berth around the magpies nest may eventually convince the nervous magpie that he does not need to deter this individual anymore because she or he poses little or no risk, and who knows, may even become a friend in future.

A sure way of escalating conflict is to fence them with an umbrella or any other device, or to run away at high speed. This human approach may well confirm for the magpie that the person concerned is dangerous and needs to be fought with every available strategy.

![]() In dealing with magpies, as in global politics, de-escalating a perceived conflict is usually the best strategy.

In dealing with magpies, as in global politics, de-escalating a perceived conflict is usually the best strategy.

Gisela Kaplan, Professor of Animal Behaviour, University of New England

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.