STEP Matters 196

- Default

- Title

- Date

- Random

- We are delighted to announce that Katie Rolls (Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University) is the winner of…Read More

- The Powerful Owl is a keystone species of bushland in eastern Australia. The survival of the current population of this…Read More

- Ku-ring-gai Council is currently undertaking a review of policy for managing recreation in bushland areas. This will cover the way…Read More

- Just months after the hard fight to get tree protections strengthened in Hornsby, council is trying to water down those…Read More

- Ku-ring-gai Council’s decision to close the Warrimoo Downhill Mountain Bike Trail was taken in July 2016 (see STEP Matters 188).…Read More

- Back in 2016 the NSW government conducted a consultation process on a Wild Horse Management Plan for Kosciuszko National Park…Read More

- The South Dural proposal for rezoning and development of rural land has fallen through thanks in no small part to…Read More

- The NSW government has finalised the Low Rise Medium Density Housing Code and Design Guide that were the subject of…Read More

- Great cities need trees to be great places, but urban changes put pressure on the existing trees as cities develop.…Read More

- With the recent introduction of the Biosecurity Act, there is now more emphasis to think about our action in terms…Read More

- The iNaturalist website has been set up as a means for citizens and scientists worldwide to record their observations of…Read More

- The perfect way to learn about the geology that underpins the landscape and diverse flora of the Sydney region A…Read More

Inaugural Winner of our Research Grant for the Conservation of Bushland

We are delighted to announce that Katie Rolls (Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University) is the winner of the inaugural John Martyn Research Grant for the Conservation of Bushland. The title of Katie's PhD is Adaptive Capacity of Widespread and Threatened Acacia Species to Climate Change. Here is what Katie has to say about herself.

I have a keen interest in conservation and ecology with particular focus on environmental gradients.

I commenced my research with the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at Western Sydney University in 2015. During my undergraduate degree I explored variation in seed coats of Acacia species along a natural gradient in the Blue Mountains where temperature decreases with altitude to determine how climate of origin and warming temperatures impact dormancy break and seed bank longevity. Throughout this time I developed a love for working in the field and being able to explore natural environments, which led me to continue my research with a master of research course. I performed a reciprocal transplant experiment researching factors that influence local adaptation and species distribution limits and looked at differences in emergence, growth and survival for Acacia species with contrasting distribution ranges when transplanted to warmer or cooler sites, as well as, within or beyond their current ranges.

I plan to build on this research in a PhD study looking into the physiological tolerance of plants through drought manipulation experiments, as well as, comparing growth of populations of seedlings within my transplant sites, which have been monitored for over a year. I hope to use the findings of my research to identify species and populations vulnerable to climate change in order to assist land managers in determining which species and populations are better suited to particular environments, and provide the scientific basis for adaptive management strategies including assisted migration to build resilience in populations under pressure from anthropogenic effects.

Powerful Owl Project Finishes but New Coalition Formed

The Powerful Owl is a keystone species of bushland in eastern Australia. The survival of the current population of this top predator is a key factor supporting the maintenance of a balance of fauna species and is an indicator of health in our ecosystems.

The Powerful Owl Project commenced in 2011 and is co-managed by BirdLife Australia’s Birds in Backyards program and the Threatened Bird Network. We reported on the activities of the Project in STEP Matters 169. Sadly, however, unless a new source of funds can be found the funding for this Project will run out on 30 June.

The Project has generated a lot of awareness of the existence of these iconic birds in Sydney’s bushland. One owl even has a Facebook page, Mikey the Owlet who lives in Byles Creek Valley Beecroft.

The objectives of the Project are:

- to engage the community to collect data to inform the conservation status of Powerful Owls in the Sydney Basin

- to identify site-specific management recommendations for all stakeholders and land managers with breeding pairs of Powerful Owls

- to inform, coordinate and support management amongst stakeholders and between land managers for conservation of Powerful Owls and other species

A major report was published in December 2014 but research has continued until now.

A conference was held on 8 June to provide a wrap up of the current data about urban Powerful Owls in the Greater Sydney Basin.

Powerful Owl Coalition

Powerful Owl Coalition

We all want to continue to give Powerful Owls a high profile. STEP and four other conservation groups from northern Sydney have got together to form a coalition with the following aims:

- to be proactive, not reactive, about their protection

- to educate and inform residents and organisations about their ecological importance

- to provide advice about habitat provision and maintenance

We have produced an information flier that will be distributed throughout local communities.

A detailed paper is being written to provide the latest understanding of the habitat conditions needed for the Powerful Owl’s survival, for breeding and foraging. Information will be tailored for all groups whose activities impact of Powerful Owls such as arborists and planners.

All groups concerned with bushland conservation are invited to join the Powerful Owl Coalition to help spread the word.

Ku-ring-gai Council’s Review of its Recreation in Natural Areas Strategy

Ku-ring-gai Council is currently undertaking a review of policy for managing recreation in bushland areas. This will cover the way people use the bushland for activities such as walking, trail running, rock climbing, abseiling, bouldering, mountain biking, orienteering and trekking. The strategy aims to support a diverse and accessible range of recreation opportunities for the community in a way that protects and enhances our local environment.

A consultation process is starting firstly with representatives of interest groups. They will then seek further input via a community meeting and a public exhibition of the draft strategy including an online forum. After consulting the community, the strategy will be finalised for adoption by council. The whole process should be completed by December 2018. We will keep you updated with developments.

Hornsby Council Proposal to Water Down New Tree Protections

Just months after the hard fight to get tree protections strengthened in Hornsby, council is trying to water down those protections on development sites.

Four months ago councillors voted unanimously for new tree protection measures. Now council is trying to insert a new section in the Development Control Plan called Tree Management on Development Control Sites that would override these protections. Instead of trees being protected under the Vegetation SEPP and the Australian Standard for the Protection of Trees on Development Sites, Hornsby Shire would go back to the bad old days of the old Development Control Plan guidelines that provided carte blanche for developers.

Is this a response to recent decisions by the Regional Planning Panel and Land and Environment Court decisions enforcing the Australian Standard and going against the council recommendations? Amending the Development Control Plan will require public consultation but we hope that the council meeting on 13 June will not proceed with the proposal.

Mountain Bikers Continue to Abuse the Environment

Ku-ring-gai Council’s decision to close the Warrimoo Downhill Mountain Bike Trail was taken in July 2016 (see STEP Matters 188). We all thought that this decision would be respected by the downhill bike riders given the strong reasons for its closure. We were wrong! This is not the only area that is being abused by these arrogant individuals. We recently discovered another track in Garigal National Park and have heard of many others. The details below explain why these cowboys must be stopped.

Warrimoo Area

Warrimoo Area

The track below Warrimoo Oval must have taken a lot of effort by several people to construct. It contains multiple jumps, ramps and curves as shown above and right. It could only be used by expert thrill-seeking riders. The independent report commissioned by council stated that the average decline is over 23% whereas the standard used for downhill trails is that they should be no more than 10%. Hence it is risky.

The major reason for closure is the ecological damage caused by the track construction and its continued use. The area contains an endangered ecological community called Coastal Upland Swamp and is also habitat for several threatened native birds, plants and animals. A STEP committee member who is a volunteer in a council-run Eastern Pygmy Possum monitoring project has observed threatened Eastern Pygmy Possums and Rosenberg’s Goanna. Under NSW and federal environmental laws, council is required to protect and conserve this ecological community and the native animals and birds that live within it.

The construction involved bush rock removal, clearing of native vegetation, removal of dead trees and wood, infection of native plants by Phytophthora cinnamomi and changes to landscape hydrology, which is adversely affecting the Coastal Upland Swamp and individual threatened species.

During a visit to the area just after the recent school holidays it was discovered that barriers and signs on the track installed by council had been shoved aside. The tyre marks along the track indicated that riders were still using the track. In 2016, council installed signs warning about video surveillance and explaining the reason for closure. These are being ignored.

This track and other downhill tracks are shown on some mountain biking websites encouraging this illegal use.

Following discussions with the local mountain bike community, council is working on options to reopen part of the trail that is south of the Coastal Upland Swamp. This involves completing an ecological feasibility study and consulting with an experienced mountain bike trail builder to see if suitable track modifications can be made with satisfactory ecological and safety outcomes. Given the steepness of the site and disturbance of the bushland reopening of the track is not guaranteed. The study will be completed by mid-2018.

Garigal National Park

We have also discovered a new mountain bike track that has been carved through high quality bushland below Cambourne Avenue in St Ives down to Middle Harbour Creek. It takes a straight line down the hill while the legal management trail zigzags across the slope.

We have also discovered a new mountain bike track that has been carved through high quality bushland below Cambourne Avenue in St Ives down to Middle Harbour Creek. It takes a straight line down the hill while the legal management trail zigzags across the slope.

This is another area where threatened species have been found, namely the New Holland Mouse and also the Eastern Pygmy Possum.

Again a lot of work has gone into constructing ramps and jumps – see photo.

We encountered two riders who didn’t care that they were breaking the law and possibly causing untold damage to threatened fauna as well as their habitat, the bushland with large numbers of species providing food for these animals.

The law is that mountain bikes are allowed in national parks and council land on fire trails, roads and management trails and signage is provided to confirm that cycling is permitted.

These riders think their needs are too important for them to have to wait for the proper process of downhill track construction. This involves surveying plant and animal species that will be affected by bike riding. A route needs to be chosen that will cause minimal damage to the bushland and then a track is built that will be safe, resilient to weather and usage pressures. This process takes time and is expensive.

STEP is not happy about the two tracks that were built in the Frenchs Forest part of Garigal National Park, the Gahnia and Serrata tracks, because they traverse high quality bushland and their usage is likely to lead to introduction of pathogens and weeds and changes in hydrology. However the quality of construction means that their usage over the past two years has not caused any obvious damage so far. We understand that these two tracks cost over

$1 million to build.

Certainly there is a growing demand for mountain biking facilities and we should be encouraging participation in active outdoor sport like this but there are many trails available that can be used legally.

There is also a strong demand for the adrenalin rush of steep downhill rides but this must not be at the expense of damaging quality bushland that is already under attack from urban development and climate change (drought, bushfire). It is not as if the riders could possibly appreciate the bushland as they speed down a hill paying close attention to the next obstacle on the track.

NPWS needs the resources to prevent the construction of these illegal tracks.

What can we do?

The best we can do is alert the authorities, national parks rangers and council staff about any track we see when out walking in the bush. Also alert your local MP about your concerns and the need for more policing of illegal activities.

Wild Horse Heritage Act Condemned

Back in 2016 the NSW government conducted a consultation process on a Wild Horse Management Plan for Kosciuszko National Park (KNP). This was to be part of the Plan of Management for KNP. Based on the assessment of the ecological impact of the horse population its main objective was to reduce the total numbers of wild horses from the estimate of 6,000 down to 3,000 in 5 to 10 years and then to about 600 over a period of 20 years. The implementation of this plan is now impossible following the passing of the Kosciuszko Wild Horse Heritage Act 2018 on 6 June.

Why are Wild Horses a Problem in Alpine Areas?

The government’s website states plainly the reasons why wild horses should be removed:

Scientists have found that feral/wild horses can damage native environments in various ways:

- increasing soil erosion, by killing vegetation, disturbing the soil and creating paths along frequently used routes

- destroying native plants, by grazing and trampling

- fouling waterholes

- collapsing wildlife burrows

- competing with native animals for food and shelter

- spreading weeds, through their dung and hair

Feral/wild horses can also pose a biosecurity risk for spread of disease, as well as pose visitor and public safety risks such as on high speed roads and highways.

Wild horses grazing on the Alpine Way

The website is also frank about the controversy and emotion associated with community attitudes to horses in the national park:

NPWS refers to the horses as 'wild horses' in an effort to maintain balance between environmental and horse advocacy stakeholder groups that regard the terms 'brumby' or 'feral' as either romanticising or being derogatory, depending on the view point.

However it is pointed out that the NPWS:

… has a legal duty to protect native habitats, fauna and flora, geological features and historic and cultural features and values within the park … and has a responsibility to minimise the impacts of introduced species, including those of wild horses.

Key Threatening Process

In April 2018 the NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee made a preliminary determination proposing that Habitat Degradation and Loss by Feral Horses, Equus caballus be listed as a Key Threatening Process in Schedule 4 of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Submissions close on 22 June.

As the determination explains:

- alpine and sub-alpine plants are slow-growing, recover slowly from disturbance and often occur in restricted areas;

- soils are fragile and the trampling disturbance caused by horses has negative impacts on a range of species, such as the vulnerable anemone buttercup Ranunculus anemoneus;

- sphagnum bogs (the principal known habitat for the endangered Northern Corroboree Frog, Pseudophryne pengilleyi) have an estimated growth rate of 3.2 to 3.5 cm / 100 years and are extremely sensitive to disturbance and trampling.

Also, many fauna species are sensitive to habitat disturbance and decreased water quality or availability. For example the critically endangered stocky galaxias fish faces extinction from trampling of their habitat.

Whether this determination, when finalised, will have any effect on horse management is now doubtful.

Brief History of Plans to Manage the Wild Horse Population

Since the current 2006 Plan of Management was implemented several reviews have been made of management plans for wild horses. Previous plans of action have proved to be ineffective in making any reduction in wild horse numbers. Trapping using lures and removal – the only method employed during the life of the 2008 Horse Plan – was costly, time consuming and did not effectively reduce the wild horse population. In addition, lack of demand for suitable domesticating (‘rehoming’) opportunities was an impediment. Often the trapped horses were in bad condition and had to be destroyed. The plan provided for aerial mustering but there would have been nowhere to send the horses. Shooting was not part of the plan.

The 2016 Plan of Management provided a comprehensive analysis of different parts of the KNP and defined strategies for a number of management zones to reduce the impact of wild horses. The techniques proposed included:

- mustering, trapping and removal from park for domestication or transport to knackery or abattoir

- trapping and culling on site if transport is not possible

- ground shooting

- fertility control

- fencing

For example the objective for the area south of Mt Kosciuszko towards Dead Horse Gap is to eliminate wild horses within five years while the aim for areas near the Victorian border east of the Alpine Way is to reduce the population as elimination would be impossible. There are other areas where horses are not present and the aim is to prevent them entering the area.

If the population increases there is an increased risk that they will enter more sensitive areas such as the Main Range. Plants in high altitude areas are currently recovering from sheep and cattle grazing that was stopped over 60 years ago.

NSW Government’s New Wild Horse Heritage Act

In a total bolt from the blue on 23 May the leader of the National Party and deputy premier, John Barilaro, presented a bill to the NSW parliament with an objective:

… to recognise the heritage value of sustainable wild horse populations within parts of Kosciuszko National Park and to protect that heritage.

The bill was passed by both houses of parliament on 6 June.

The act is very short on detail. It provides for the preparation of a wild horse heritage management plan for KNP. The draft plan is:

… to identify the heritage value of sustainable wild horse populations within identified parts of the park and set out how that heritage value will be protected while ensuring other environmental values of the park are also maintained.

There is a total conflict of interest here! There is no attempt to define heritage or what a sustainable population means. Do horses have more heritage than native animals? Is it sustainable from the point of view of the horse population only or within the context of the ecology of the whole KNP? The only opportunity for expert input to the draft is from the National Parks Wildlife Advisory Panel but only after the plan has been drafted.

The act will specifically prohibit shooting of wild horses in the national park. It will also limit any other management of wild horses to ‘highly sensitive alpine areas’ and such management will be limited to relocation and rehoming.

The act provides for the establishment of a Community Advisory Panel that will work on the draft plan but it has no requirement for representation by people with scientific qualifications in areas associated with the conservation of nature, nor does it require qualifications in cultural heritage research. It will include alpine tourism and horse riding operators. This arrangement will see scientific advice all but removed from the management of wild horses in KNP.

A major concern is that the act will prevail over the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974, Section 81(4), and will prevail over the 2006 Kosciuszko National Park Plan of Management, a legal instrument established under that act.

Strong Reaction to the Act

The passing of the act is another example of the NSW government’s disdain for national parks. The horse population will continue to increase. Do they see another tourism opportunity of more people trekking or horse riding in KNP to see wild horses? Perhaps these tourists will be horrified by the sight of starving horses and the damage they are doing as they search for edible grass?

Public condemnation has come from many directions:

- Australian Academy of Science wrote a letter stating the act placed ‘a priority on a single invasive species over many native species and ecosystems, some of which are found nowhere else in the world’

- Scientists from the United Nations body, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature wrote a letter to the environment minister Gabrielle Upton stating that ‘damage to the ecosystem and biodiversity values of the Kosciuszko national park would be detrimental to the reputation and status of Australia and NSW’s record for nature conservation’

- David Watson, an ecology professor at Charles Sturt University, resigned his membership on the NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee citing the government’s wilful disregard for science

- RSPCA that worked on the 2016 plan as part of the expert panel said the act makes it impossible to conserve the unique environmental values of Kosciuszko as it will veto evidence based management

The only hope is for a change of government at the March 2019 election.

Relief as South Dural Development Proposal Withdrawn

The South Dural proposal for rezoning and development of rural land has fallen through thanks in no small part to the 6,000 residents who wrote submissions and stood together to fight this inappropriate plan.

In 2013, developers Folkestone-Lyon lodged a planning proposal seeking the rezoning of 240 ha of rural land across South Dural, with almost 2,900 new homes to be built. About a quarter of the land to be developed contains high conservation value bushland including critically endangered Blue Gum High Forest. The plan resulted in community outrage and calls for major infrastructure upgrades before the proposal could be considered.

A peer review conducted on behalf of Hornsby Council identified technical gaps in the planning proposal, and the Planning Department recently announced that the proposal could no longer be supported, ‘due to the identified cost to government related to the provision of infrastructure’. Current road congestion is bad enough even before such a development were to be added.

Medium Density Housing Code Implemented with some Improvements

The NSW government has finalised the Low Rise Medium Density Housing Code and Design Guide that were the subject of consultation during 2016. This code allows one and two storey dual occupancies, manor houses and terraces to be built using the complying development approval pathway. Unless the type of development is not permitted in a residential zone under a council’s Local Environment Plan (LEP) a single dwelling can be redeveloped into 2, 3 or 4 dwellings depending on the size of the block. Design guidelines will have to be met but councils will not have control on the rate of take up of this opportunity.

The code is due to take effect in July but local concerns about congestion and over-development have become so great that the government was forced to defer implementation in four council areas. The deferral is only for a year however. This applies to Ryde, Lane Cove, Canterbury Bankstown and Northern Beaches but other councils are also asking for a deferral. Many areas of Sydney are struggling to cope with recent heavy development and infrastructure is inadequate. Is the one year deferral enough time to catch up?

Some councils, like Ku-ring-gai, already have provisions in their LEP that prevent this type of development in low density residential zones. Other councils want (and need) to be able to control the location of this infill housing option and are still working on a housing strategy that would define where this new category of development could occur. These are the councils that are asking for a deferral. They have just woken up to the potential consequences.

STEP’s submissions on this new type of complying development criticised the ad hoc nature of the application of the code and the broad implications of converting low density into higher density housing. There could be a huge rush of landowners taking up the opportunity to expand the value of their property. Councils need to able to specify areas where this type of development is not suitable, for example, because it does not fit in with the topography or character of particular areas or there is insufficient transport. At least the NSW government has recognised that councils need more control.

Design Guide Improvements

The Design Guide has been developed in partnership with the Government Architect’s Office, and aims to improve design by addressing layout, landscaping, private open space, light, natural ventilation and privacy.

The Design Guide has been improved by defining minimum standards for greenery on the blocks. The government has finally taken on board the importance of trees and gardens in reducing the heat island effect and improving local amenity. The guide specifies:

- minimum landscaped areas

- retention of trees especially along a boundary except where removal is approved by council

- planting of a tree in the front yard if the street setback is 3 m or more (mature height 5 m) and in the back yard (mature height 8 m)

- minimum soil volume to support the trees

- an ongoing maintenance plan

The ongoing question will be how that can these guidelines be enforced and the gardens kept alive. Councils will have a big responsibility perhaps?

Tree Bonds can help Preserve the Urban Forest

Great cities need trees to be great places, but urban changes put pressure on the existing trees as cities develop. As a result, our rapidly growing cities are losing trees at a worrying rate. So how can we grow our cities and save our city trees?

Tree bonds have recently been proposed by Stonnington City Council as a way to stop trees being destroyed in Melbourne’s affluent southeastern suburbs.

Tree bonds are a common mechanism for protecting trees on public land, but have so far had limited use on private land. A tree bond requires a land developer to deposit a certain amount of money with the local authority during development. If the identified tree or trees are not present and healthy after the development, the funds are forfeited.

The size of the bond can be established based on estimated tree replacement costs, and/or set at a level that is likely to achieve compliance (likely to be thousands or tens of thousands of dollars).

Why are trees important in cities?

The concept of an 'urban forest' includes all the trees and plants in cities. This includes tree-lined city streets as well as parks, waterways and private gardens. The urban forest contributes substantially to the quality of life of all urban dwellers, both human and non-human, and is increasingly used to adapt cities to climate change.

Trees cool the streets, filter the air and stormwater, and create a sense of place and character. They provide food and shelter for insects, birds and animals.

There is growing research evidence for the physical, mental and social health benefits of urban trees and green spaces. Many local councils such as Brimbank and Melbourne are investing substantially in tree planting to increase these benefits.

However, despite new tree planting on public land, tree canopy on private land is declining.

What can we do to protect trees?

There are a range of existing policy and land use planning measures focused on landscaping requirements for new development. Recently, the Victorian government introduced minimum mandatory garden area requirements. Some Melbourne councils, including Brimbank and Moreland, have also included planning scheme requirements for tree planting for multi-dwelling developments.

Other mechanisms for protecting urban trees on private land include heritage and environmental overlays within local planning schemes, and listings of significant trees and heritage trees.

However, penalties, monitoring and enforcement of tree protection bylaws have not kept pace with the pressures of urban change.

If penalties are insignificant relative to development profits, developers can easily absorb the costs. If monitoring is weak and removal has a good chance of going undetected, tree protection is more likely to be ignored. And if enforcement is weak, or there is a history of successful appeal or defeat of enforcement, many trees may be at risk of removal.

Even when it is successfully pursued, after-the-fact planning enforcement action is a particularly unsatisfactory recourse for tree removal. Replacement trees may take decades to match the quality of mature trees that were removed. What is needed, then, are mechanisms that prevent tree removal in the first place.

Increasing use of tree bonds

The advantage of tree bonds is that they place the onus of proof of retention on developers, rather than the onus of proof of removal on local councils. If a tree is removed, the mechanism is already in place to monitor (the developer needs to demonstrate the tree is still there) and penalise (the financial penalty is already with the enforcing body).

However, tree bonds still do not guarantee tree protection. Some mechanisms used to impose tree bonds may be vulnerable to challenge. For example, historically in Victoria, the planning appeals body VCAT has struck out conditions imposing tree bonds, arguing that punitive planning enforcement measures should be used where trees are removed.

Even where bonds can be imposed and enforced, developers may still be able to demonstrate that trees are unsafe or causing infrastructure damage, and thus need to be removed. In these circumstances, it is often hard to prove otherwise once the tree has been removed.

Nurturing an urban forest

Ultimately, if a landowner is hostile to a tree on their land, that tree’s health and survival can be imperilled, whether through illegal removal, neglect, or applications for removal based on health and safety grounds. It is therefore important that building layout and design realistically allow space for trees to flourish and be valued by landowners.

The urban forest needs protecting and enhancing. This calls for a range of policy mechanisms that work together to retain mature trees, maintain adequate spacing around them, and encourage residents to value and protect the trees around their homes.

![]() Tree bonds provide an attractive solution for local governments in the absence of a strong land use policy framework for protecting trees.

Tree bonds provide an attractive solution for local governments in the absence of a strong land use policy framework for protecting trees.

Joe Hurley, Senior Lecturer, Sustainability and Urban Planning, RMIT University; Dave Kendal, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Management, University of Tasmania; Judy Bush, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub, University of Melbourne, and Stephen Rowley, Lecturer in Urban Planning, RMIT University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

New Project to Investigate Sterilising Woody Weeds to Stop Seed Spread

With the recent introduction of the Biosecurity Act, there is now more emphasis to think about our action in terms of weed spread and dispersal. The act specifically focuses on the shared liability relating to containment and control of weeds.

There is a significant and unresolved conflict between the retention of trees of species that are invasive and ecologically-damaging but are also recognised for their cultural, historic or aesthetic significance.

Camphor Laurel is one such species. They were planted extensively for amenity or cultural reasons but the species readily invades natural areas, impacting on biodiversity and ecosystem functions. Individual trees can generate copious progeny annually through seed production and dispersal.

Killing such trees will certainly stop seed set but this may result in community angst. There are instances where the removal of such trees is curbed by community or historic values. Protestors may only have their thoughts on a few issues, such as shade or the loss of very old picturesque trees, however we must consider that the seed from some of these invasive species may be transported long distances via birds and deposited in other areas.

Is it possible to preserve these trees whilst preventing them from producing seed?

Chemicals can be used to Modify Growth

We are all too familiar with herbicides and their primary role to kill weeds. However, there are many herbicides that have been used to modify the growth of plants without the aim of death. Other active ingredients (non-herbicides) have also been identified to alter plants growth for a desired outcome.

New Project

A federally funded project commenced in July 2017, courtesy of the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources and the lead agency MidCoast Council and other collaborating agencies. The primary aim was to undertake some research in the following two years to scope a handful of chemicals to de-flower or prevent fruit from developing on African Olives and Camphor Laurels. There is potential to use this technique, if successful, on other species. However, as there is limited project time it was decided to stay focused on these species.

African Olive

African Olive is a garden escape plant and has become a serious weed in bushland. It can further spread to and heavily impact upon agricultural land. More than 4,000 hectares of dense African Olive infestation has been identified across the western Sydney region alone. African Olive was listed as a key threatening process to biodiversity by the NSW Scientific Committee in 2010.

It is estimated that African Olive is having a negative impact on at least 25 endangered ecological communities as well as 13 threatened flora and 4 threatened fauna species in NSW. African Olive has further been listed in the Global Invasive Species Database. African Olive out-competes established native vegetation, casting dense shade which prevents the regeneration of native plants. Infestations can alter the floristic structure and habitat value of remnant bushland areas.

Camphor Laurel

Camphor Laurel is considered a threatening weed under similar listings to African Olive. They have the ability to adapt to the disturbed environment, have prolific seed production and a rapid growth rate as well as a lack of serious predators or diseases, they also possess many specific attributes which enhance its weed status.

Camphor Laurels are ecosystem changers. They have a tendency to form single species communities and exclude most other tree species, including desirable native vegetation. They have a very dense, shallow root system which, when accompanied by the shading provided by the canopy, suppresses the regeneration of native seedlings. They have the ability to replace and suppress native vegetation and have an allelopathic effect on other species.

Interim Results from Year 1

The list of potential chemical candidates for testing was rather lengthy and after an extensive literature review the list was trimmed down to three chemicals for Camphor Laurels and two for African Olives. Growth habit of the weed plays a large role into determining the type of treatment selected and how it is applied. A species like African Olive is often multi-stemmed and would be impractical for stem injecting whereas the single stemmed Camphor Laurel trees are ideal for a range of chemical deliver systems.

A long dry period of weather from winter to spring played havoc on the flowering times and synchronicity of Camphor Laurels and African Olives. Fortunately significant rains fell in early October to rejuvenate the weeds, however flowering was still not ideal. Timing of treatments was closely linked to flowering, namely near early-mid flower bud opening stage.

Assessment of treatment impacts on flowering or fruiting capacity of the weeds was undertaken in March and May 2018, but careful consideration was made to foliage changes. An ideal treatment is one that suffers no foliar damage while completely aborting reproductive issue.

The interim results from the African Olive experiments suggest this species is rather difficult to selectively control flowering/fruiting without severely affecting foliage.

The best compromise appeared to be treatment A with two times concentration that reduced fruit setting by 90% with a foliage damage score of 3 out of 10 which equates to some very noticeable symptoms from which the plant will take some time to recover. Four times concentration reduced fruit setting by 98% but with much more severe foliage damage. There is scope to apply various rates around this two times rate in the second year of the project, to better fine tune treatment outcomes.

It appears treatment A (same treatment for African Olives) was the most suitable for temporarily sterilising Camphor Laurels. It subtly made the foliage paler whilst significantly reducing reproductive capacity. Treatment B achieved very little. Treatment C will be tested in year 2 at much lower rates due to excessive foliage damage in year 1.

Concluding Comments

The second and last year of testing will be focused on getting consistency and robustness of the likely treatments that may be considered for registration or permits. The key to success is developing a treatment that can be easily and evenly applied that doesn’t leave obvious scarring of bark while achieving near perfect seed set control and barely noticeable effects on foliage. Timing of treatments could be investigated in subsequent projects, however there is only enough time to investigate rate responses of treatment A.

Fingers crossed for a better season than 2017-18.

This is a shortened version of an article in the Autumn 2018 edition of A Good Weed, the newsletter from the NSW Weed Society. Here’s hoping this idea can be extended to many more weed species, in particular privet.

Ku-ring-gai BioBlitz

The iNaturalist website has been set up as a means for citizens and scientists worldwide to record their observations of wildlife. It includes a system for verification of species photographs by other members.

The iNaturalist website has been set up as a means for citizens and scientists worldwide to record their observations of wildlife. It includes a system for verification of species photographs by other members.

A local 15-year-old has used his initiative to raise awareness of the great biodiversity in our region by setting up a local BioBlitz group. You can post any nature sightings made around Sydney, as well as improve your knowledge of the local flora and fauna and meet like-minded nature enthusiasts near you.

He organised a BioBlitz from 14 to 15 April in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. Nine people participated who recorded 185 observations of 112 species. The most notable observation by a couple of STEP members was a Yellow-tufted Honeyeater.

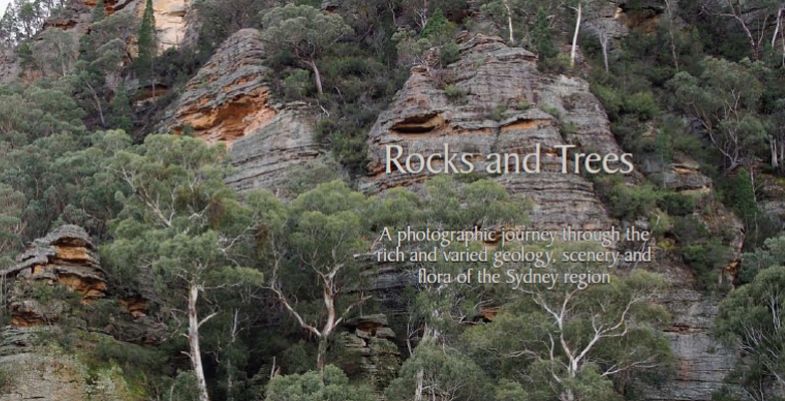

John Martyn’s New Book, Rocks and Trees

The perfect way to learn about the geology that underpins the landscape and diverse flora of the Sydney region

A photographic journey through the rich and varied geology, scenery and flora of the Sydney region

Rocks and Trees captures the dramatic scenery of the Greater Blue Mountains, the beauty of the coastline and the great sweep of plains west of the CBD, but its main purpose is to highlight the geology and flora and their interrelationships. The book journeys from the Illawarra along the coast to Newcastle and inland to the Greater Blue Mountains, staying within the framework created by the massive sandstones and conglomerates of the Triassic Narrabeen Group.