Displaying items by tag: longwall coal mining

Thirlmere Lakes and East Coast Lows

Thirlmere Lakes lie in an area that was subject tectonically to weak uplift and gentle monoclinal warping at the ill-defined southern end of the Lapstone Structural Complex, a feature that is highlighted further north by the bold escarpments of the Lapstone Monocline and the Kurrajong Fault. The chain of five shallow, swampy lakes lies in the remnants of an alluvium-filled, mature, incised-meandering river system that ancestrally drained westwards into the Wollondilly catchment. However, as a consequence of the gentle upwarping plus relative subsidence of the adjoining Cumberland Basin, the drainage direction in the north-east sector of the chain has been reversed due to headwater capture by Cedar Creek, which flows via Stonequarry Creek south-eastwards to the Nepean. The lakes are essentially stranded on a gentle watershed between two drainage systems.

The catchment area of the lakes is relatively small, roughly 10 km2 of Hawkesbury Sandstone spurs and side-valleys, and there is no long distance drainage flow-through along the dismembered ancient river course. But they overlie a substantial thickness of water-saturated alluvium whose water leaks away very slowly, and are in one sense the surface manifestation of its rising and falling water table.

Rises and Falls in Water Level

Latter day fluctuations in the water levels in these ancient lakes have been the subject of much recent debate centred around the possible effects on aquifers of longwall coal mining in nearby Tahmoor Colliery, operated by Xstrata. Other suggested factors have been the pumping of aquifers for local agricultural purposes.

Levels were particularly low in June 2010 (photo bottom left) and then rose quite slowly – below many people’s expectations (photo at the top of the page was taken in May 2015). However, the lakes now (March 2017) are as full as they’ve been in recent decades (photo bottom right).

You can easily access the rainfall data of the Bureau of Meteorology’s automatic rain gauge located near Buxton 3 km to the south, and from it you can deduce some interesting correlations.

The low water levels of 2010 following the exceptionally dry year of 2009 (photo bottom left) occurred when only 588 mm was recorded against a mean of 856 mm. In strong contrast, in 2017 (photo bottom right) is a hangover from the massive east coast low falls of June 2016 when 387 mm was recorded at Buxton, including a one day fall of 188 mm (contrast the wettest monthly total for 2009 of only 97 mm). Rains from east coast lows can overwhelm everything over huge areas, create massive floods, and fill and sometimes overflow our storage reservoirs. The plants don't need all that extra water, especially in winter, and what doesn't run off will bypass their root systems and swell the aquifers, including those that feed the lakes.

And what of the gradual rise in lake levels from 2010 onwards that had many people puzzled? Well, four out of the six years from 2010 to 2016 brought above average rainfall, peaking at 971 mm in 2013, and the other two were only slightly below – 736 mm in 2011 and 841 mm in 2014. The maximum one day fall in that period was 133 mm in January 2013 and January and February of that year scored a combined total of 326 mm. This was thus a slightly wetter than average time and the photo at the top of the page shows Lake Werri Berri recovering, roughly half full, in May 2015, a year in which the preceding month of April was the wettest one with a total of 164 mm.

Are we still pointing a finger at Xstrata's longwall mine system? Well this is a personal opinion and don't quote me as an expert, but I believe it can only be a minor factor at most; rainfall versus evaporation is demonstrably the major control, as has been the case from historical records and one which is built into the conclusions of the report cited below. How climate change will affect things in the future is unknown, though there is already evidence of increasing intensity within rainfall events. More ones like June last year can only be good for the lakes.

Recommended reading: Thirlmere Lakes Inquiry Final Report of the Independent Committee, 23 October 2012

John Martyn recently visited Thirlmere Lakes to see how the area has fared during the recent period of freak weather. In STEP Matters 186 we wrote about concerns that the significant drop in water levels since the mid-1980s was due to longwall mining. It seems the picture has changed considerably.

Thirlmere Lakes, Perhaps another Victim of Longwall Mining

The previous issue of STEP Matters 185 described the risks to Sydney’s water catchment in the Illawarra region from longwall mining. Research is now pointing to mining also being a culprit in the drying out of Thirlmere Lakes. Thirlmere Lakes National Park is part of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. The two largest of the five lakes are currently empty and the other three are depleted.

The report, published by the UNSW Centre for Ecosystem Science, found that the dropping of water levels coincided with the onset of longwall coal mining in the mid-1980s, with the lakes having continued to dry out since then. Longwall coal mining is thought to have fractured the aquicludes that constrain the groundwater aquifers, causing diversion of groundwater resources. Another factor could also be considerable pumping of groundwater.

The report's findings contradict a 2013 NSW Government Commission of Inquiry which stated that:

… changes in the water levels in Thirlmere Lakes over the past 40 years are due to climatic variations such as droughts and floods.

The recent heavy rain that has led to nearby Warragamba Dam almost overflowing has had very little impact on the water levels in the lakes.

Commenting of the report, UNSW wetland ecologist Prof Richard Kingsford said gum trees were encroaching on the dry lakes. ‘What we are seeing here in terms of the vegetation is the slow death of a wetland,’ he said.

The Thirlmere Lakes are the 15-million-year-old remnants of a river whose original flow direction was stalled and gently reversed by mild tectonic tilting, and according to Prof Kingsford, hold a rich geology. The implications are significant for the ecological character of the Thirlmere Lakes.

There are many affected obligate aquatic species or species reliant on wet habitats, including:

- five species of waterbirds (Australasian Bittern Botaurus poiciloptilus, Australian Painted Snipe Rostratula australis, Great Egret Ardea alba, Cattle Egret Ardea ibis and Latham’s or Japanese Snipe Gallinago hardwickii)

- one fish species (Macquarie perch Macquaria australasica)

- two frog species (giant burrowing frog Heleioporus australiacus, Littlejohn’s tree frog Litoria littlejohni)

- three plant species (smooth bush pea Pultenaea glabra, Kangaloon sun orchid Thelymitra Kangaloon and the aquatic water shield Brasenia schreberi) that are listed as threatened

Interestingly, Thirlmere also carries the freshwater sponge Radiospongilla sceptroides.

The report has serious implications for governments and their responsibilities for managing the values of Thirlmere Lakes National Park along with the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. These major changes in flooding regimes to Thirlmere Lakes will continue to degrade the Thirlmere Lakes National Park and its ecological, cultural and recreational values. The lakes were once popular with swimmers and canoeists.

Mine owner, Glencore announced in June that operations will be reduced and the mine will be closed in 2019 as a result of low coal prices. The local Wollondilly Council and Friends of Thirlmere Lakes are calling for action to restore the Lakes. Council has suggested that artificial injection of fresh water should be considered. It is a theory supported by groundwater expert Dr Philip Pells, who said recovery of the water table may otherwise take decades.

‘It's not beyond the realm of possibility to pump water up from Warragamba Dam, cycle it back through here, and it goes back down to Warragamba Dam,’ Dr Pells said.

Longwall Mining in Sydney’s Water Catchments

The battle continues against coal mining under the water catchments in the Illawarra but there are some hopeful signs that the NSW Government could start to see sense about the environmental damage that is occurring.

Sydney is fortunate to have a pristine water supply on its doorstep. In theory the water catchments are protected as development and agriculture are prohibited. In the Special Areas in the Illawarra catchment anyone entering the land without permission can be fined $44,000. These catchment areas contain bushland and natural systems such as coastal upland swamps that slow water movement and filter the water that flows into dams such as the Avon and Cataract. Many other cities have to pay millions of dollars to operate synthetic filtering systems of their water supply.

Mining has been undertaken in the Illawarra region since the 1880s but in the early days the methods used were pick and shovel and later machinery that took out small sections of the coal seam. The mine ceilings and walls were supported by the bord-and-pillar method. Since the 1960s the technology for longwall mining has been developed that vastly increases the rate of removal of coal and, incidentally, cuts the level of employment significantly.

The coal is removed by a massive machine that shears away the wall beside it whilst hydraulic powered supports hold up the roof. As the coal is removed, the machine supports are moved forward and the roof is collapsed behind them. The areas of rock extracted are 150 to 400 m wide, 4 m high and can extend for several kilometres. When one longwall is completed another is started leaving a rock support of about 50 m in between.

As such a large section of coal is removed the roof above the longwall collapses. Depending on the nature of the rock above, minor cracking can occur in the strata above, but frequently major cracking has occurred right up to the surface. Cracking leads to water leaking from the creeks and wetlands, pollution from the release of excess minerals from the underlying rocks and cliff falls.

Concerned locals have been documenting the damage over the past ten years and have been leading a campaign to raise awareness of the damage and making detailed submissions explaining the concerns about current and future development applications. This group was formalised by the creation of the Protect Sydney’s Water Alliance in 2013, a network of more than 50 community groups from across Sydney, the Illawarra, Southern Highlands and Blue Mountains.

Illawarra Mines

The Illawarra mines all produce coal for steel making. They make up a complex array of cavities under a region that has reliable rainfall and therefore is a significant source of drinking water for Sydney as well the large population of the Wollongong region. The main miners are:

- Wollongong Coal Ltd, listed on the ASX but majority owned by Indian company Jindal Steel and Power, with mines at Russell Vale near Cataract Dam and Wongawilli further south. The Russell Vale mine has run out of approvals. The Wongawilli mine was suspended but the company has now applied to extend its licence and reopen the mine.

- Illawarra Coal owned by South32, a company demerged from BHP that operates the Dendrobium mine near the Avon Dam.

- Peabody Energy operates the Metropolitan mine near the Woronora Dam.

There are two current controversial applications for extension of current mining operations.

Wollongong Coal

In Issue 180 of STEP Matters we wrote about the Planning Assessment Commission’s (PAC) report on the application to develop eight new longwalls. Wollongong Coal failed to convince PAC that it can expand the Russell Vale colliery without causing substantial and irreversible damage to Sydney’s drinking water supply.

As the mining approvals have run out the mine was closed six months ago, and the entire workforce was sacked. But the company seems undaunted and has continued with the expansion application.

The second review of the mine expansion by PAC has just been released and has reinforced the previous opinions. Despite acknowledging the short-term benefits of the project – which includes the provision of 300 jobs for five years, about $23 million in royalties to the NSW Government and $85 million in capital expenditure and other direct and indirect flow-on effects – PAC concluded that:

On the basis of the information provided, the Commission is of the view that the social and economic benefits of the project as currently proposed are most likely outweighed by the magnitude of impacts to the environment.

In particular, PAC identified the risk of water loss, risk to upland swamps, noise impacts on nearby residents, potential hydrogeological impacts and a loss of ecosystem functions.

PAC is not satisfied that the project is consistent with the State Environmental Planning Policy (Sydney Drinking Water Catchment) 2001 that it would have a neutral or beneficial effect on water quality in the catchment area. The magnitude of water loss is uncertain with the projected range from the proponent and Water NSW varying from minimal to 2.6 GL/year. PAC considers this is a high risk situation. Sydney Water has valued the potential water loss at a cost of $23 million over 25 years. The cost of government subsidies are also estimated to be $23 million. The expansion is economic as well as environmental madness.

A separate issue is the financial viability of the company itself.Wollongong Coal currently has no capacity to repay its debts unless it is thrown another financial lifeline by parent Jindal Steel & Power (Australia) Pty Ltd. The company is currently suspended from trading on the Australian Stock Exchange. If the project falls over the company has no capacity to remedy any damage it could cause to the catchment.

Under legislation passed in 2014 in response to ICAC findings the Minister for Resources can deny a mining application if the proponent is not deemed to be ‘fit and proper’. The Environmental Defenders Office has presented a strong portfolio of evidence that Wollongong Coal fails that test. The minister’s response is so far non-committal. This is the first time a decision is being made under this legislation so it may take a while to consider the precedent it may establish.

The final decision is in the hands of the government.

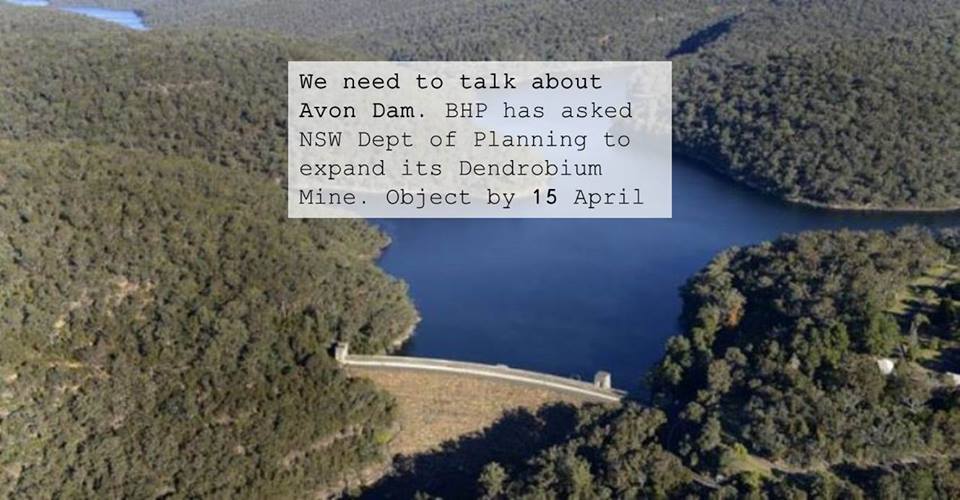

Dendrobium Mine

The Dendrobium Mine was approved in principle by a Planning Assessment Commission in 2001 and significantly expanded in 2012 despite great concern to those watching the significant damage that had already occurred to every swamp that was above an existing longwall.

The company is now applying for a further expansion closer to Avon Dam. Protect Sydney's Water Alliance objected to the expansion for several reasons:

- proven ongoing damage caused by current longwall mining

- failure by the proponent to take any steps to mitigate damage to swamps in previous longwalls

- failure by the proponent to prove that swamps can be rehabilitated or to undertake agreed research in this area

- the Dam Safety Committee clearly states in its submission that no longwall mining should take within 300 m of the full supply level of Avon Dam (the proposed longwalls will be within 250 m of the dam)

- the cumulative Impact of this mining on the catchments over the long term (as per PAC 2016 rejection of Russell Vale expansion)

- the dubious nature of jobs claims and the lack of any evidence that royalties or bond can ever cover the cost of rehabilitation

The closing date for submissions is 15 April. Click here to make a submission.

Metropolitan Mine

This mine was given approval for major expansion in 2009 despite major damage already occurring to the Waratah Rivulet and failed attempts to remediate the cracks using polyurethane resin injections. Peabody Energy is currently in financial straits because of the fall in the coal price. However, it is expected that the company will apply for a further expansion in the near future.

Significance of PACs Wollongong Coal Report

The issues raised in the PACs report apply to all the other mines in the catchment. It is hoped that heed will be taken of the strong opinions of the report when the current expansion plans of the Dendrobium and, possibly, future Wongawilli and Metropolitan mine expansion applications are considered.

Russell Valley Colliery Expansion Thwarted

Previous issues of STEP Matters (Issue 173, p7–8 and Issue 175, p2) have highlighted the damage that is occurring in Sydney’s southern water supply catchment in the Woronora area caused by underground longwall coal mining. Cracking of the surface has drained upland swamps and creeks that are the filter system and source of water flowing into the Cataract and Woronora dams.