Displaying items by tag: water level

How Should the Flood Risk from the Hawkesbury Nepean be Managed?

The NSW government thinks that raising the spillway wall of Warragamba Dam by 14 m will significantly reduce the risk of floods inundating homes in western Sydney. But experts have questioned whether the raising will achieve worthwhile benefits and whether the ecological damage can be acceptable. They argue the water levels in the dam storage should be better managed instead.

Brief History of Sydney’s Water Supply

The first water supply dams built to supply Sydney were the Upper Nepean dams (such as Avon and Cataract Dams) that still provide 20-40% of our supply. When this supply became inadequate the next step was the construction of Warragamba Dam that commenced in 1948 and was completed in 1960. The resulting storage in Lake Burragorang is one of the largest reservoirs for urban water supply in the world.

Following 1988 and 1989 high rainfall years, the NSW government re-evaluated the potential rainfall and flood risks and raised the dam wall by 5 m and constructed an auxiliary spillway on the east bank of the dam.

Back in February 2007 the Warragamba Dam water supply fell to its lowest recorded level of 32.5% after the prolonged drought from 1998. In response conservation measures and water usage restrictions were introduced. The desalination plant was built at Kurnell but this has hardly been used as we have had a period of above average rainfall ever since. Now the concern is flood risk. In 2012 and 2015 water had to be released to prevent a mass overflow. Currently the level is around 91%.

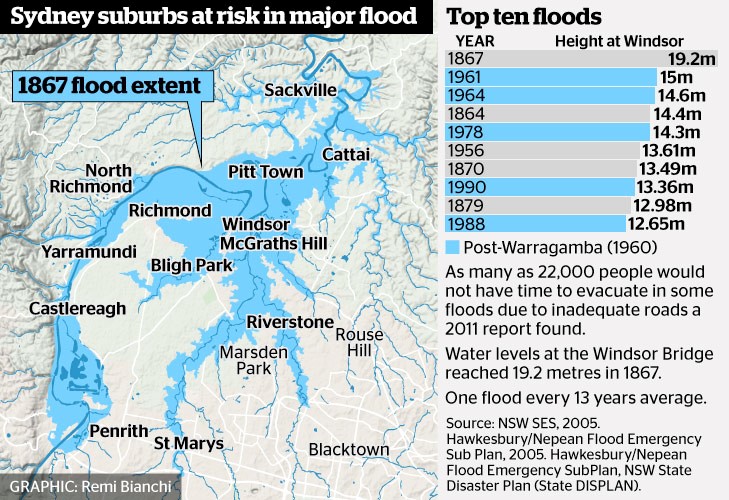

The benchmark for flood risk often used is the worst recorded flood that occurred in 1867 when the water height at Windsor Bridge was 19.2 m. This figure (from Sydney Morning Herald) provides data of past major floods and the flood extent in 1867.

The benchmark for flood risk often used is the worst recorded flood that occurred in 1867 when the water height at Windsor Bridge was 19.2 m. This figure (from Sydney Morning Herald) provides data of past major floods and the flood extent in 1867.

According to the State Emergency Service, the estimated rainfall in 1867 in the lead up to the flood was 770 mm over three days averaged over the entire Nepean River catchment. The flood experience would be different now because several dams have been built in the Nepean catchment.

Government Proposals for Flood Mitigation

The high rainfall experienced in 2013 led to the need to release water causing minor flooding. The NSW government initiated another Hawkesbury Nepean Flood Management Review.

The review concluded that there is no simple solution or single infrastructure option that can address all of the flood risk in the Hawkesbury Nepean Valley floodplain. The risk will continue to increase with population growth. Evacuation is the only mitigation measure that can guarantee to reduce risk to life. According to the State Emergency Service a flood at the 1867 level would now lead to the evacuation of 90,000 people, damage to 12,000 homes and a cost of $5 billion.

As Prof Paul Boon explained during his STEP talk on 11 July on the Hawkesbury River, the topography of the river valley creates several challenges in understanding and managing flood risk.

The Hawkesbury has two main sources, the huge catchment of rivers that flow into Warragamba Dam that has its own flood plain from Emu Plains to Castlereagh. Then the Hawkesbury starts at Yarramundi when water sourced from the Grose Valley catchment in the Blue Mountains joins the Nepean. There is a flood plain around Richmond and Windsor through to Cattai but then more rivers join in and the valley narrows again with steep sandstone gorges and many twists and turns. This means that floods can bank up and spread out over broad areas of western Sydney.

Recommendations of the Review

Some points from the first review report are:

- Due to time constraints the review only assessed the flood mitigation potential of raising of the Warragamba Dam wall crest by 15 and 23 m. Pre-feasibility construction costs and reduction of flood levels have been calculated. However, economic, environmental and social costs and benefits have not been included at this stage. Detailed cost benefit analysis will be conducted for the options for the raising of Warragamba Dam in Stage 2 of the review.

- The review also assessed the potential for changing the operation of Warragamba Dam at its current configuration to provide for flood mitigation. Options examined different ways to create airspace to capture a portion of incoming floodwaters, by reducing the full supply level of the dam, ‘pre-releasing’ water if major flood inflow are expected based on forecast rainfall, or ‘surcharging’ the dam level during floods using the dam’s gates.

- The review concluded that only minor floods, below levels where significant damages occur, could be mitigated using the current dam unless its role as the main water supply to Sydney was compromised. It was also concluded that ‘pre-releasing’ of water from the dam prior to a flood was limited due to the inaccuracies in rainfall forecasts beyond three days, and the potential to increase or prolong downstream flooding.

- Reducing the full supply level of Warragamba Dam provides only a reduction in minor flooding and needs to be assessed against the impacts on Sydney’s water supply. The review considered lowering the full storage level by 2, 5 and 12 m, and concluded that the 2 m lowering had minimal flood mitigation benefits, and the

12 m lowering would have significant impacts on Sydney’s water supply. - Stage 2 of the review will further analyse surcharging the gates and reducing the full supply level for the mitigation of smaller floods, including the operational risks and the impact on Sydney’s water supply.

Even though Stage 2 of the review has not been completed, WaterNSW has been preparing environmental impact statements based on a proposal to raise the dam wall by 14 m and made a referral under the Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act on specific matters of national environmental significance.

The intended operation after the spillway wall is raised is for water to be held back during a heavy rainfall event and then released slowly in the following weeks. This will provide additional time for evacuation and reduce the downstream flood peak. The stated intention is not to increase the current overall water storage level.

Environmental Impacts

The Colong Foundation for Wilderness has expressed serious concerns about the impact of the current proposals. The fundamental points made in their Colong Bulletin (July 2017) are:

The Colong Foundation for Wilderness has expressed serious concerns about the impact of the current proposals. The fundamental points made in their Colong Bulletin (July 2017) are:

- Raising the dam level does not deal with the flood waters coming from the major rivers further downstream such as the Grose, Macdonald and Colo.

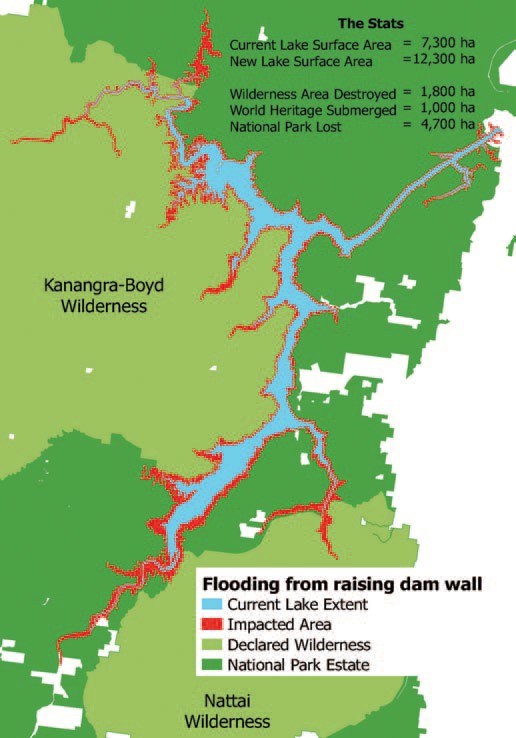

- The extra water storage is intended to be temporary but the vegetation around Lake Burragorang and its tributaries that will, nevertheless, be flooded for several weeks will die leaving ugly scaring of the banks. The upstream flooding will impact the Kedumba and Colong River valleys that are part of the World Heritage listed wilderness areas. A further 1800 hectares could be flooded and another 33 km of rivers inundated.

- The backed up water in the Kedumba River will be visible from Echo Point, the iconic lookout in the Blue Mountains at Katoomba. The figure illustrates the projected increase in areas affected by inundation.

- Even flooding from a 1 in 50 year flood will extend 5 km into the Kedumba Valley and cause the death of 40% of the critically endangered Camden White Gum Forest. This species is listed as vulnerable under the Threatened Species Conservation Act. The Department of the Environment includes the forest in the Kedumba Valley as part of the Save Our Species biodiversity restoration program with an objective ‘to secure the species in the wild for 100 years and maintain its conservation status under the TSC Act’. Methinks WaterNSW should talk to the Department of the Environment.

- Aboriginal cultural heritage will be destroyed.

- Classic bushwalking areas will be lost, historic campsites drowned and access restricted. Bushwalkers are drawn to the pristine Kowmung River, a wild river that has inspired generations of walkers.

Can the Water Storage Level be Managed Instead?

Assoc Prof Stuart Khan, an expert in water engineering, disagrees with the need to raise the dam level. Management of the water level by controlled releases is a safer option so that the dam is never full. The desalination plant that can supply 15% of Sydney’s water needs, could be put to use when the need arises by way of earlier releases. Basically he disagrees with the review’s conclusions.

This is a fascinating risk management problem. Should we:

- reduce the water level if a period of heavy rainfall is projected and thereby reduce the water supply capacity with the backup of the desalination plant; or

- increase the dam wall at great expense and environmental damage that would threaten the tourism industry but still not eliminate the flood risk

Whatever option is taken flood risk cannot be eliminated. However the government is still going ahead with allowing massive population increase in the flood plains of the Hawkesbury Nepean system. As population grows the warning time needed to organise evacuation will increase.

Given the improvement in longer term weather forecasting. The government must explore options for smarter use of risk management techniques to adjust the storage levels. Raising the dam wall ignores this potential and could be a waste of $700 million.

Also future governments could easily be tempted to use the raised dam wall to increase water storage permanently to provide water supply for Sydney’s projected massive increase in population.

Other Serious Water Management Issues

As reported in the Sydney Morning Herald on 21 August, coal mining is impacting on the Sydney water supply catchments but the government is not carrying out adequate monitoring.

The 2016 Audit of the Sydney Drinking Water Catchment was tabled in parliament on the quiet. The National Parks Association discovered the report. It revealed that groundwater losses from longwall mining under the catchments in the Woronora areas has not been quantified. This is despite mining company reports have indicated that about 25 to 40 million litres a day have been entering the mines.

The 2013 audit report revealed that research was underway into the connectivity of surface and groundwater but no results have been revealed in the 2016 audit. This is not good enough given that these mining companies are still applying to expand their mining operations under the catchment.

There are also problems with coal mines leaking toxic chemicals into catchment rivers. Examples are the Springvale mine that has been pumping untreated waste into the Coxs River and the closed Berrima mine that has been leaking pollutants into the Wingecarribee River.

Thirlmere Lakes and East Coast Lows

Thirlmere Lakes lie in an area that was subject tectonically to weak uplift and gentle monoclinal warping at the ill-defined southern end of the Lapstone Structural Complex, a feature that is highlighted further north by the bold escarpments of the Lapstone Monocline and the Kurrajong Fault. The chain of five shallow, swampy lakes lies in the remnants of an alluvium-filled, mature, incised-meandering river system that ancestrally drained westwards into the Wollondilly catchment. However, as a consequence of the gentle upwarping plus relative subsidence of the adjoining Cumberland Basin, the drainage direction in the north-east sector of the chain has been reversed due to headwater capture by Cedar Creek, which flows via Stonequarry Creek south-eastwards to the Nepean. The lakes are essentially stranded on a gentle watershed between two drainage systems.

The catchment area of the lakes is relatively small, roughly 10 km2 of Hawkesbury Sandstone spurs and side-valleys, and there is no long distance drainage flow-through along the dismembered ancient river course. But they overlie a substantial thickness of water-saturated alluvium whose water leaks away very slowly, and are in one sense the surface manifestation of its rising and falling water table.

Rises and Falls in Water Level

Latter day fluctuations in the water levels in these ancient lakes have been the subject of much recent debate centred around the possible effects on aquifers of longwall coal mining in nearby Tahmoor Colliery, operated by Xstrata. Other suggested factors have been the pumping of aquifers for local agricultural purposes.

Levels were particularly low in June 2010 (photo bottom left) and then rose quite slowly – below many people’s expectations (photo at the top of the page was taken in May 2015). However, the lakes now (March 2017) are as full as they’ve been in recent decades (photo bottom right).

You can easily access the rainfall data of the Bureau of Meteorology’s automatic rain gauge located near Buxton 3 km to the south, and from it you can deduce some interesting correlations.

The low water levels of 2010 following the exceptionally dry year of 2009 (photo bottom left) occurred when only 588 mm was recorded against a mean of 856 mm. In strong contrast, in 2017 (photo bottom right) is a hangover from the massive east coast low falls of June 2016 when 387 mm was recorded at Buxton, including a one day fall of 188 mm (contrast the wettest monthly total for 2009 of only 97 mm). Rains from east coast lows can overwhelm everything over huge areas, create massive floods, and fill and sometimes overflow our storage reservoirs. The plants don't need all that extra water, especially in winter, and what doesn't run off will bypass their root systems and swell the aquifers, including those that feed the lakes.

And what of the gradual rise in lake levels from 2010 onwards that had many people puzzled? Well, four out of the six years from 2010 to 2016 brought above average rainfall, peaking at 971 mm in 2013, and the other two were only slightly below – 736 mm in 2011 and 841 mm in 2014. The maximum one day fall in that period was 133 mm in January 2013 and January and February of that year scored a combined total of 326 mm. This was thus a slightly wetter than average time and the photo at the top of the page shows Lake Werri Berri recovering, roughly half full, in May 2015, a year in which the preceding month of April was the wettest one with a total of 164 mm.

Are we still pointing a finger at Xstrata's longwall mine system? Well this is a personal opinion and don't quote me as an expert, but I believe it can only be a minor factor at most; rainfall versus evaporation is demonstrably the major control, as has been the case from historical records and one which is built into the conclusions of the report cited below. How climate change will affect things in the future is unknown, though there is already evidence of increasing intensity within rainfall events. More ones like June last year can only be good for the lakes.

Recommended reading: Thirlmere Lakes Inquiry Final Report of the Independent Committee, 23 October 2012

John Martyn recently visited Thirlmere Lakes to see how the area has fared during the recent period of freak weather. In STEP Matters 186 we wrote about concerns that the significant drop in water levels since the mid-1980s was due to longwall mining. It seems the picture has changed considerably.