Displaying items by tag: biodiversity

New nature laws announced but the most important parts are missing

One of the Albanese Government’s promises was to take action to halt the alarming decline in our biodiversity and rewrite the ineffective laws that were highlighted in the Samuel Review into the Environment and Biodiversity Conservation Act. In December 2022 the government announced what was dubbed the Nature Positive Plan with a comprehensive list of actions that are intended to be implemented.

The key part of the plan is to implement national environmental standards that will set the outcomes that the laws are seeking to achieve.

The timing of the introduction of the plan was to carry out consultation in stages and release an exposure draft of the legislation by the end of 2023. We are nowhere near that objective; in April the Minster for the Environment, Tanya Plibersek, announced that legislation will soon be presented to parliament to set up two new agencies:

- Environmental Protection Agency, to act as a national watchdog for nature

- Environmental Information Australia so everyone has access to authoritative data on our environment

But these are the easy parts. The major parts of the plan have been deferred with no time frame.

What use is a watchdog with no standards to enforce? The government appears to have given in to the mining lobby. There are also reports of warnings from the Western Australian Labor government of a backlash in the electorally critical state. This is so frustrating when the need for comprehensive action is so urgent.

The major environment groups that were involved in the consultation process are worried that the process will be drawn out for a long time. The government has made a promise so we must be optimistic that the steps outlined in the Nature Positive Plan will be implemented. But how much more destruction will occur in the meantime?

Currently several coal mine expansions are up for approval that will cause loss of important habitat. An example is the Moolarben mine near Mudgee owned by Yancoal. The expansion application before the NSW government would make the mine one of the largest in Australia. Even according to the mine manager it would destroy 113 ha of critical koala habitat. The company says they will create offsets on their own land. Development assessments should be made in the context of the total cumulative impacts on habitat.

Multiple threats to koala habitat

Koala habitat is under multiple threats from forest logging, mining and urban expansion. The promised Great Koala National Park is one area where logging is continuing. Plus, there is a sustained attempt by the logging industry to ‘redefine’ the borders of the park. Little is known about koala habitat being cleared on freehold land – there is no accurate data or independent assessment required.

Actions that are being taken

Nature repair market

Legislation to roll out a ‘nature repair market’ was passed in March 2024. This legislation aims to facilitate voluntary or philanthropic investment in conservation projects by giving them a definable value with government-backed quality assurance of processes to manage the market for these biodiversity credits.

To make these credits worthy of investment and tradeable, they need a governance framework, measurement systems, certification, registration, contracting, trading, monitoring, reporting, accounting, auditing, and a bureaucracy for administering, consulting and advising on all of it. All this is still in the process of being established. The CSIRO has been engaged to lead a research collaboration to design and pilot an ecological knowledge system for the market.

This all sounds like an offset system that has a bad reputation from the experience of the biodiversity offsets that enable destruction of habitat under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act. The Greens made sure the legislation prevented the credits from being used as offsets.

Environment Protection Agency

This authority will be responsible for:

- issuing permits and licenses

- project assessments, decisions and approval conditions

- compliance and enforcement

It would be able to issue stop-work notices, fines and be able to audit businesses to check their compliance with developments approvals. It will also oversee enforcement of other environmental laws such as animal trafficking, recycling and sea dumping.

Environment Information Australia

This agency will:

- provide government and public with authoritative data and information about the environment

- develop an online database to help give business quicker access to data

- publish State of the Environment reporting every two years

- report on progress towards environmental outcomes

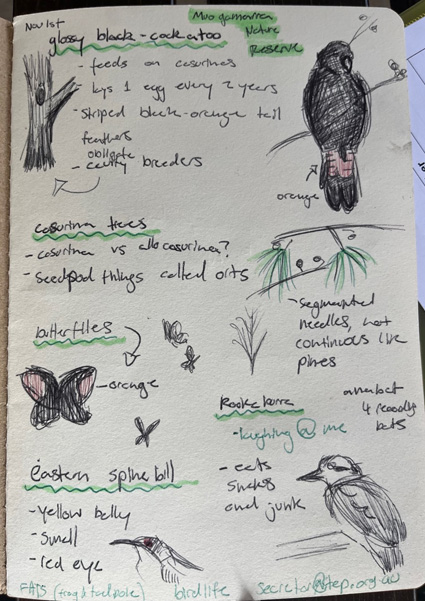

Biodiversity camp – Muogamarra Nature Reserve

‘What an amazing opportunity …’ was a student response overheard during a lunch conversation at the recent biodiversity survey held at Muogamarra Nature Reserve on 1 November 2023. Now in its second year, the biodiversity camp coordinated by Gibberagong Environmental Education Centre (GEEC) and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service provides an opportunity for students to learn about their local environment, fauna, wildlife survey techniques and careers in the environmental field.

GEEC staff, teachers and students were overjoyed by the support offered by our local community-based environmental organisation, STEP. STEP so willingly offered a grant to help financially support this important project. With living costs at a high, the grant provided by STEP helped us subsidise the cost of the experience to students, purchase ten pairs of binoculars and help pay for secondary teachers to attend.

Year 10 students from Ku-ring-gai HS and Turramurra HS were invited to apply for this opportunity. Upon meeting these students in the morning, one could immediately pick up on the passion and interest of these young people.

It was most disappointing for all involved to learn of a total fire ban on the Tuesday. This meant that all tracks were closed and our extensively planned overnight biodiversity camp could not run in the original format. Unfortunately, we could not do the overnight component. Due to the challenges in coordinating such events, were very lucky to proceed with a full day event on the Wednesday.

It was most disappointing for all involved to learn of a total fire ban on the Tuesday. This meant that all tracks were closed and our extensively planned overnight biodiversity camp could not run in the original format. Unfortunately, we could not do the overnight component. Due to the challenges in coordinating such events, were very lucky to proceed with a full day event on the Wednesday.

There was a silver lining in running a modified program. As we travelled into Muogamarra early in the morning we spotted two families of Glossy Black-Cockatoos. This was an amazing experience and opportunity for our students to observe this beautiful species feeding early in the morning on specific feed trees. It also provided our resident Glossy Black-Cockatoo expert and NPWS Chase Alive Volunteer, Barbara Hamilton with the opportunity to collect valuable observational data on these birds.

During the morning, the students were very fortunate to listen to two expert presentations. The first presentation was delivered by Kathy Potter from the Frog and Tadpole Study Group (FATS). Kathy so generously shared her expertise on local frog species, identification, habitats and how we can encourage frogs into our urban landscape.

This was then followed by an excellent presentation by Barbara Hamilton, Chase Alive Volunteer and local bird expert. Barbara spoke taught the students about local bird identification, evolutionary history of birds, bird distribution and how to attract a variety of birds to our home environments.

Armed with our fantastic binoculars, funded fully by STEP, we were set to conduct our survey walks. We listened and looked for all animals, especially birds. The students also collected the wildlife cameras that were set-up in the weeks prior to the survey.

Unfortunately, we did observe a European Red Fox on the wildlife camera. This will be provided to the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service for future management of the site.

Unfortunately, we did observe a European Red Fox on the wildlife camera. This will be provided to the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service for future management of the site.

Despite the limitations on the surveys, we did manage to identify over twenty species of animals during the survey. This information will be provided back to NPWS. Ideally, we would like to have completed more surveys during the evening and very early morning.

The major benefit of this fieldwork is the seed that has been sown in our next generation. The students were overwhelming enthusiastic about learning about our local environments, especially our fauna. They felt more connected to their local environment and have left with not only more knowledge about fauna, habitats, and survey techniques. Most importantly, the students left with an even deeper passion and love for our natural environment. So much so, they are going to do follow-up fauna surveys at their own schools as well as present their learnings to their broader school community.

Gibberagong EEC would like to express our deepest gratitude to all involved – teachers and students, STEP, NPWS, Kathy and David Potter (FATS), Barbara Hamilton (Chase Alive) and Gibberagong staff.

Brad Crossman, Teacher, Gibberagong Environmental Education Centre

30 x 30 Biodiversity Agreement

There is a plethora of international agreements that relate to the protection of the Earth’s biodiversity. The overarching convention is the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) that was signed by 150 government leaders at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. Examples of other agreements are the Ramsar Convention that aims to protect internationally significant wetlands and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). They don’t all work in isolation thank goodness! There is a Liaison Group of the Biodiversity-related Conventions.

The most recent major strategic plan to address the sad state of global biodiversity was the agreement to adopt the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets for 2010–20 period. The meeting was held in Aichi Prefecture in Japan; hence the name.

However, according to an assessment by the United Nations, none of the 2020 Aichi targets were met. At the moment, committing to the Aichi targets is voluntary and results from each party are self-reported to the CBD. Because these agreements are non-binding, the path to translating and implementing targets into national legislation is unclear.

One major reason for the lack of progress has been the continuation of subsidies and other incentives potentially harmful to biodiversity. An estimated $500 billion in government subsidies potentially cause environmental harm, according to the UN report.

Progress in establishing protected areas

One area of progress is the target relating to the establishment of protected areas. The objective was that by 2020, at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water, and 10% of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved. This target has been nearly met with 15% of land and 7% of oceans being protected by 2020.

What happens post 2020?

The countries that signed the CBD have their own COPs (Conference of the Parties) just like the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The 15th meeting is a whole series of meetings with the first held in 2021 to develop a strategic plan post 2020. This meeting was hosted by China from the city of Kunming. Parties to the CBD adopted the Kunming Declaration to keep the political momentum of the negotiations delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Kunming Declaration recognised that progress has been made in the last decade, under the 2011–20 Strategic Plan for Biodiversity but expressed grave concern that such progress has been insufficient to achieve the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. It acknowledges that:

the unprecedented and interrelated crises of biodiversity loss, climate change, land degradation and desertification, ocean degradation, and pollution, and increasing risks to human health and food security, pose an existential threat to our society, our culture, our prosperity and our planet.

The declaration includes a long list of principles that are being developed into a Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework for actions. The framework is built around the recognition that urgent policy action is required to turn around the trend of biodiversity loss. The objective is that the trend should stabilise in the next 10 years (by 2030) and allow for the recovery of natural ecosystems in the following 20 years. The ultimate goal is to achieve the Convention’s vision of ‘living in harmony with nature by 2050’.

The 30 × 30 pledge

The Declaration notes a first step, the pledge by many countries to protect and conserve 30% of land and sea areas through well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures by 2030. This known as the 30 × 30 pledge.

More than 100 countries have pledged to adopt this goal including the USA. Joe Biden announced his commitment a week after he became president.

There are lots of other goals in the Kunming Declaration. The details of measures to achieve these goals will be hammered out at COP15 of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in Montréal, Canada, from 5–17 December 2022.

Australia’s response

The Minister for the Environment, Tanya Plibersek, in releasing the 2021 State of the Environment Report, announced that Australia will aim to exceed the 30 × 30 agreement. This will require additional 50 million hectares of landscape to be protected. This does not need all to be in national parks.

Under the government’s plan 20 places and 110 species will become the focus of conservation efforts selected based on several factors including their uniqueness and risk of extinction. The areas include the forests of Far North Queensland, Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory and Kangaroo Island in South Australia.

This announcement raises many questions. As the Chief Conservation Officer of the World Wildlife Fund points out, Australia has more than 1,900 listed threatened species. This plan picks 110 winners. It’s unclear how it will help our other ‘non priority’ threatened species such as our endangered greater glider.

Given the powers that the states have over management of protected areas and land clearing, how will the selection of the additional protected areas be determined? Can it be on a bioregional basis that ignores state boundaries. How will the ocean areas be defined – as sanctuary zones?

An article on the NPA NSW website explains the task at hand. The WWF commissioned protected areas spatial analyst Dr Martin Taylor to estimate what it would take to create a truly ecologically representative network of protected and conserved areas as part of the 30% target.

Protected land objectives required for NSW

In NSW, 7.6 million hectares of land occurs in the National Reserve System, equivalent to just 9.6% of the total land area. Moreover, more than 60% of ecosystems have less than 15% of their area protected.

Achieving significant progress towards protecting 30% of NSW would require not just a significant expansion of legal protection, but also revegetation and rewilding of millions of hectares of long-cleared lands in the sheep and wheat belt. This would require significant investment from state and federal governments as well as corporate and philanthropic support through natural capital markets. In some cases creation of new protected areas may be contested by some locals. It is also becoming less realistic as global heating and extreme weather events worsen.

Completing the transition out of native forest logging could secure an additional two million hectares of public native forests. Transfer of Crown lands, including large areas of travelling stock routes with high conservation values, to NPWS or Indigenous communities for conservation management, would need to be a major contributor to the 30% target. Supporting First Nations to voluntarily declare additional Indigenous Protected Areas could play a key role. Purchases of large pastoral stations in the Western Division could provide land justice for Indigenous communities through handback or co-management, and diversify rural economies as global heating increasingly makes some grazing and farming enterprises sub-economic.

The Biodiversity Conservation Trust’s capacity to support private landholders to establish conservation agreements would need to be greatly expanded – without relying upon perverse offsets – including through innovative partnerships that also deliver carbon outcomes with social, cultural and economic co-benefits.

$9m funding to revive Sydney Harbour biodiversity

In August the NSW Environment Minister, James Griffin, announced a project, dubbed the Seabirds to Seascapes project that aims to restore Sydney Harbour by bringing back lost biodiversity, improving water quality and increasing carbon storage. The project will restore habitats for some of our iconic species such as penguins, seals, seahorses and turtles

This project includes three elements:

- restoring Sydney Harbour's marine ecosystems by installing living seawalls, and replanting seagrass meadows and kelp forests

- supporting the future of little penguins by conducting the first ever state-wide little penguin census to better understand their population size and how they're responding to threats such as climate change, along with the restoration of seagrass meadows and kelp where they thrive

- helping fur seals thrive as a species by conducting a seal survey to identify their preferred habitat, breeding grounds, diet and key threats – seal numbers are growing, as evidenced by more sightings around the harbour and along the coast

The NSW Environmental Trust is granting $6.6m to the project, with partners contributing a further $2.5m in kind. The project is being led by the NSW Department of Planning and Environment, in partnership with the Sydney Institute of Marine Science (SIMS – see note below), Taronga Conservation Society Australia and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Note: SIMS is a collaborative marine science hub between UNSW Sydney, UTS, University of Sydney and Macquarie University. SIMS has more than 100 scientists and graduate students associated with the Institute, representing a broad diversity of skills in marine science.

Living Seawalls, an award-winning innovation

The world has been experiencing a construction boom in our seas. Globally, the area of the seafloor impacted by built infrastructure is greater than the area of the world’s mangrove and seagrass forests. Structures such as seawalls, pilings, pontoons and marinas are built for diverse purposes such as shoreline protection, recreational activities and energy generation, but lack the complexity required for a biodiverse marine environment. In particular, the flat and featureless surfaces of marine constructions provide little space for marine plants and animals to live, and few protective refuges from predators and environmental stressors, driving this reduced diversity and favouring the presence of pest species.

By blending ecological concepts and engineering in creative design, a team from SIMS is reviving our increasingly urbanised oceans through the development of affordable, adaptable and scalable methods of ecologically enhancing structures. Living Seawalls has shown that, despite marine construction being a large part of the problem, it can also be part of the solution.

The addition of living seawalls creates surface texture and microhabitats for organisms like shellfish, mussels and algae, which can regrow significantly in a year.

Living seawalls will be installed across nine locations in the harbour, where hundreds of kilometres of smooth harbour walls have made it difficult for organisms to take hold.

The Living Seawalls project (www.livingseawalls.com.au) has won the 2022 Banksia Foundation Award for Biodiversity. They have been installed in Singapore, Europe and two other locations in Australia. See.

Seagrass meadows, a vital habitat

Seagrasses (Posidonia australis) provide critical habitat for conservation icons like seahorses, as well as acting as nursery grounds for many fish species. They are very effective at capturing carbon as they can store carbon at up to 40 times faster than terrestrial forests.

These marine plants grow in shallow estuary waters. They have become severely threatened by human activities like coastal development, boat anchorages, pollution and sedimentation. The decline in these meadows has been so severe that six meadows have been formally listed as endangered under the Commonwealth Government (EPBC Act) and the NSW government.

Part of the replanting program involves asking local communities to collect shoots that naturally become detached after large storms.

Kelp forests

Crayweed (Phyllospora comosa) is a golden seaweed that forms extensive underwater forests and promotes biodiversity by providing habitat, food and shelter for hundreds of species, including crayfish and abalone. They also act as underwater forests, capturing carbon and creating oxygen.

However, crayweed completely disappeared from the Sydney metropolitan region from Palm Beach to Cronulla in the 1980s due to pollution and has never returned.

Report card on our biodiversity

Australia is losing more biodiversity than any other developed nation. Already this year the charismatic and once abundant gang gang cockatoo has been added to our national threatened species list, the koala has been listed as endangered and the Great Barrier Reef suffered another mass bleaching event.

The Australian public consistently rates the loss of our unique plants and animals as a key concern. Indeed, in a recent poll of 10,000 readers of The Conversation, 'the environment' was identified as the second-biggest issue affecting their lives, behind climate change at number one.

The Coalition has been in government since 2013. So what has it done about the biodiversity crisis? Unfortunately, the state of Australia’s plants, animals and ecological communities suggests the answer is - not nearly enough.

In fact, as the extinction crisis has escalated, protection and recovery for threatened species has declined. Poor decisions are contributing to the problem, rather than solving it.

The sorry state of Australia’s biodiversity

Australia has formally acknowledged the extinction of 104 native species since European colonisation, but the true number is likely much higher.

Threatened bird, mammal and plant populations have, on average, halved or worse since 1985. Species recently thought to be safe – such as the bogong moth, gang gang cockatoos, and even the iconic koala – are being added to the global and national threatened species lists following drought, catastrophic fires and habitat destruction.

Today, 19 ecosystems show clear signs of collapse. This includes the Great Barrier Reef, savannas, mangroves, tropical rainforests, and tall mountain ash forests. These losses have profound ramifications for clean air and water, productive agriculture, pollination, and well-being.

Biodiversity is a crucial part of Australia’s national identity and Aboriginal culture. It delivers billions of dollars in tourism revenue and underpins most sectors of our economy.

It’s important for our health, too. COVID lockdowns recently brought the critical role of nature to our well-being into sharp focus, with thriving biodiversity shown to deliver avoided costs to the healthcare system.

Ignoring key recommendations

A 2018 Senate inquiry into the extinction crisis of Australian animals (fauna) concluded that native fauna was declining. It found biodiversity protection was under-resourced and failing, and Australia urgently needs an independent environmental regulator.

In 2022, the federal Auditor-General reviewed the government’s implementation of Australia’s threatened species legislation, finding:

limited evidence that desired outcomes are being achieved, due to the department’s lack of monitoring, reporting and support for the implementation of conservation advice, recovery plans.

The national Threatened Species Strategy focuses on 100 species and a few iconic places. But more than 1,800 species and ecosystems are threatened with extinction.

And economic analyses indicate we currently spend about around 7% of the targeted A$1.6 billion per year required to halt species loss and recover nationally listed threatened species.

These findings were reinforced in 2020 by a major independent review of Australia’s environment law – Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

The review by Professor Graeme Samuel made 38 recommendations, but almost none have been implemented. They include establishing an Environment Assurance Commissioner, rigorous national environmental standards and resourcing compliance and enforcement of environmental regulations.

Failure to protect what we have

Land clearing is a key threat to Australian wildlife, yet the government has not made meaningful progress to halt it.

The hectares cleared in New South Wales over the last decade have tripled, and a staggering 2.5 million hectares have been cleared in Queensland between 2000 and 2018.

Worryingly, more than 7.7 million hectares of threatened species habitat have been cleared since the EPBC Act came into force (between 2000 and 2017), including 1 million hectares of koala habitat.

Invasive species – such as cats, foxes, rabbits, deer and buffel grass – continue to wreak havoc on many of our most endangered species.

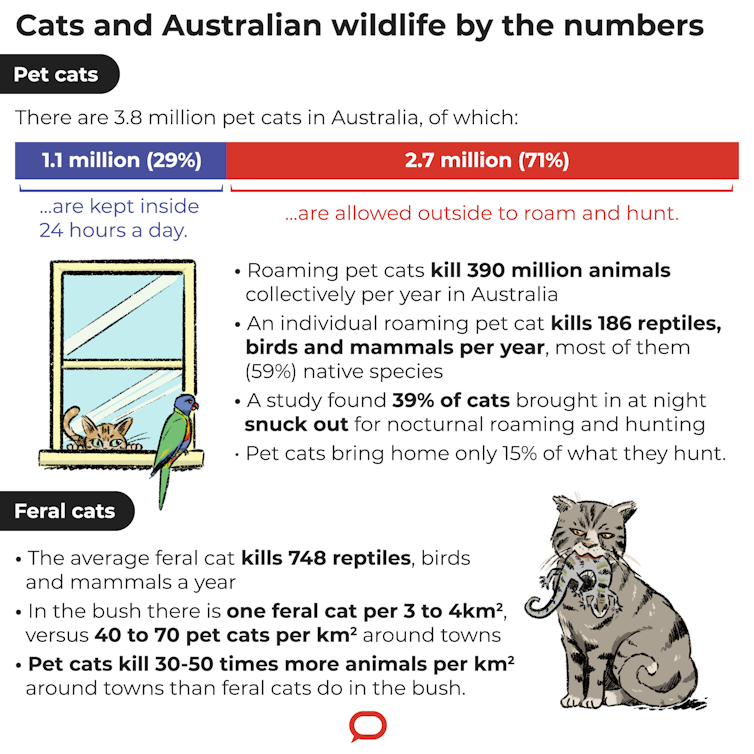

Cats alone kill 1.7 billion native animals each year and threaten at least 120 species with extinction. While feral predator control has received some focus, the effort still falls well short of what’s required.

Lack of transparency and accountability

Official reviews have consistently found the federal government’s approach to protecting biodiversity lacks transparency and accountability.

Questions have also been raised about the federal government’s delay in releasing its five-yearly State of the Environment Report ahead of the election.

And investigations have raised serious concerns about how the government handled decisions regarding grasslands illegally destroyed by a company part-owned by a government minister.

A key advisor to the government recently labelled a major scheme to promote forest restoration as carbon credits as environmental and taxpayer 'fraud'.

A federal integrity commission, if it existed, could have explored these cases.

The government also continues to back activities that cause damage to biodiversity, including the fossil fuel and forestry industries.

On agriculture, the government is pursuing a 'biodiversity stewardship' policy, to financially reward farmers for protecting wildlife.

But ongoing approval of unsustainable land management practices, particularly land clearing (of which agriculture is responsible for the lion’s share) will likely overshadow any stewardship gains.

So what’s needed to prevent future extinctions?

Labor has not yet revealed its full suite of environment policies. This week it told Guardian Australia it will release more details before the election, and has called on the government to release the State of the Environment report.

So what policies are needed to reverse the biodiversity crisis? The answer is: spend more and destroy less.

Just two days of Coalition election promises (estimated at $833 million per day) would fund recovery for Australia’s entire list of threatened species for a year.

Systems for protecting biodiversity need stronger legal mandates and less discretion for ministers to override decisions about project approvals, species listing and other matters.

Biodiversity should be integrated into key aspects of government practice. For example, it makes no sense to invest in protecting koalas while simultaneously approving koala habitat clearing.

And we need investment in every threatened species, not just a hand-picked few.

Finally, transformative policies are needed to support the substantial opportunities to enhance and restore biodiversity. This includes:

- using nature to help mitigate climate change

- green recovery of the economy post-COVID

- finding ways to farm profitably while enhancing biodiversity

- designing cities where people and nature can both flourish.

The fate of nature underpins our economy and health. Yet in the election campaign to date, there’s been a deafening silence about it. ![]()

Sarah Bekessy, Professor in Sustainability and Urban Planning, Leader, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University and Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Ecology, School of Ecosystem and Forest Science, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New hope for the environment following the election

At last we have some good news to report. The country is breathing a sigh of relief following the defeat of the Morrison government, even expressing whoops of joy.

The major areas relating to the environment where we are hoping for big new effective policy change are outline below.

Energy

The new Albanese government has been thrown in the deep end with a crisis in energy supply. Gas and petrol prices have soared because of the war in Ukraine. Electricity has been in short supply because of the failure of several coal-fired power stations, the need to use expensive gas and the rise in demand in response to the cold snap. All these factors highlight the abysmal management and policies of the Morrison government.

At last we will see some real action with rapid expansion of the transmission grid to facilitate the use of renewable energy and more support for these projects. There is more positive action proposed to support the transition to use of electric vehicles. These actions will take time to be effective but 2030 is not far away!

The emissions reduction target will be improved to a 43% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030. This is still viewed as inadequate by the Climate Council and the ‘teal’ candidates. Labor is still not strong enough on closing down coal mines and stopping new projects.

A review will be held of Australia’s controversial carbon offset programs, to be conducted independently of government departments and agencies. This is vital for the effectiveness of plans to reach net zero emissions – see the previous STEP Matters.

Land clearing

Labor has promised to set a domestic target to protect 30% of land and 30% of sea areas by 2030.

Great Barrier Reef

Labor has promised to increase funding to tackle agricultural pollution, more sustainable fishing practices and research into thermal tolerant corals. But the really meaningful solution is rapid reduction in carbon emissions

Murray–Darling Basin

After years of the Nationals favouring big irrigators and undermining the Murray– Darling Basin Plan, the new government has a chance to restore more natural flows to the rivers of the Murray–Darling Basin, establish integrity and transparency for water management, and get the plan to revive our rivers back on track.

The review of the Murray–Darling Basin Plan will occur during this term of parliament, so there is the possibility of increasing water recovery targets towards what the science says is necessary for healthy rivers, wetlands and floodplains.

Biodiversity

The previous environment minister, Sussan Ley, refused to release the State of the Environment Report that was finalised last December. The new Minister for Environment and Water, Tanya Plibersek has indicated that it tells an ‘alarming story’ of decline, native species extinction and cultural heritage loss. She will release the report in a speech to the National Press Club on 19 July.

Labor has promised to create a federal Environmental Protection Agency to improve environmental compliance, information and analysis. We hope this agency will be genuinely independent and have real teeth.

Furthermore, there’s been a failure to address one of the most egregious failings of our system which is to evaluate cumulative impacts of projects on the environment as opposed to a license by license approach.

NSW State of the Environment report – a mixed result

The EPA released the three-yearly State of the Environment Report (SoE) in February. There are some pluses but mostly it paints a sorry picture. It boils down to the human impact from climate change and population growth.

The Australian SoE was sent to the Minister for the Environment, Susan Ley, in December. But it is has not been made public yet. The minister is required to table the report in parliament within 15 sitting days of receiving it. Parliament has sat only briefly this year so the government is not legally required to release it until the next parliament forms. What is she trying to hide?

For a change the NSW report does acknowledge the significance of population growth ‘population growth is the main driver of environmental issues’.

Yet, the NSW government’s top bureaucrats have urged the premier, Dominic Perrottet, to take a national leadership position and advocate a temporary five-year doubling of the pre-pandemic migration rate, which would increase the NSW population by about 2 million in 5 years. The argument is that this would rebuild the economy and address labour shortages.

The economy seems to be doing all right, thank you! Labour shortages seem to be a perpetual issue despite high immigration for most of this century. Perhaps it is more to do with wages being too low in the affected sectors of the economy. In 2018, Gladys Berejiklian, called for a pause to enable the state’s infrastructure to catch up. This still hasn’t happened.

Some pluses in this SoE report include:

- Air and urban water quality are generally good but the state’s major inland river systems continue to be affected by water extraction, altered river flows, loss of connectivity and catchment changes such as altered land use and vegetation clearing.

- Greenhouse gases are declining having fallen by 17% since 2005. Renewable energy sources have grown but they are still only 19% of electricity power in 2020. But, unlike the federal government, there is actually a plan to get to net zero by 2050.

- About 9.6% of NSW is conserved in the public reserve system. The rate of new reservations has increased markedly, with around 305,000 ha being added to reserves since 2018.

What about biodiversity?

The story on biodiversity is very different. Much loss can be attributed to the Black Summer bushfires but the downward trend has accelerated due to climate change and land clearing.

Improvements have been made through the Saving our Species program. $175 million has been allocated to the program for the 10 years to 2026, and $240 million has been allocated over five years to support a greater commitment to long-term conservation of biodiversity on private land.

Land clearing is the greatest threat to biodiversity. Land clearing and logging of native forests continue at record levels (54,500 hectares in 2019). Unrealistic logging contracts are driving the rates of tree felling which is crazy when several reports have shown that the government is losing money on logging operations. Land clearing is now so bad that in February the koala was declared an endangered species under the Commonwealth EPBC Act.

Money is going into saving species but the amount of land clearing is likely to be creating more threatened species. Invasive species are also a major threat. The regulatory framework under the Biodiversity Conservation Act is failing as was predicted by environment groups and the EDO.

Feeling adrift in a sea of false hope

A couple of months ago, I sat in on an Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) event via Zoom for its donors and supporters that promoted its latest climate change campaign. As a long-serving councillor and former vice president of ACF, I was interested to hear about their campaign plans, which they explained are based on a poll of 15,000 people who indicated a desire for firm action on climate change. However, at the end of it, I felt isolated and alone. I felt I had moved on in my thinking, while ACF has not.

The presentations by senior ACF staff were earnest and uplifting and the comments posted in response were enthusiastic and supportive. But I felt myself estranged from the event. I found myself recalling how often, over my 30 years of enthusiastic involvement with ACF, I had felt uplifted and inspired by the same style of presentations by ACF’s key personnel. Now, not so and it felt a bit like having lost a faith.

So, what has changed for me as ACF barrels along in its customary manner? It comes down to a realisation that ACF, and environmentalism more generally, is stuck with talking about the symptoms of the environmental crisis, while ignoring the underlying causes. It is also locked into a largely fruitless campaign mode that is focused on targeting marginal seats in each Federal election. This has been its style since I joined its council in the 1980s and it remains a deeply entrenched, culturally embedded modus operandi.

The ACF people are intelligent, well-meant and deeply committed environmentalists, and for that they have my great respect. But they, and seemingly their supporters and donors who joined in this event, now appear to me to be tunnel-visioned and misguided in their fervour. First, and foremost, there is the assumption that climate change is the major existential threat that ACF and the wider environmental movement must address. It is their highest priority. And second, there is the additional assumption that this threat can be averted through a political campaign focussed on key marginal seats that will somehow bring about a radically different response. I hear myself thinking, ‘same old, same old’, looking back over forty years of ACF campaigning strategy. When will the penny drop that this is a fruitless strategy?

I could have submitted a comment to the event along the following lines:

When will ACF connect its climate change and biodiversity work to a deeper sustainability agenda that encompasses population growth, consumption, economic growth and technology – the underlying drivers of imminent collapse?

That would have been a real ‘party pooper’ contribution that I am sure would not have been welcomed by the ACF organisers on the night. It probably also would have been dismissed as inappropriate or irrelevant by most of the supporters and donors participating in the event.

The reality is that these deeper and more complex issues have been either ignored or dismissed by most ACF staff for much of its existence. This is despite the efforts of a number of its elected councillors and former Presidents over many years (ranging from Sir Garfield Barwick in the early 1970s to Emeritus Professor Ian Lowe more recently), to draw attention to them. The focus within ACF staff remains on an agenda dominated by the twin environmental pillars of climate change and biodiversity. But it would be unfair to level this criticism only at ACF. The environmental movement more generally, both here in Australia and in most other Western countries overseas, has largely displayed the same myopia in framing their campaigning and advocacy efforts.

As to the reasons for this behaviour, a fellow ex-ACF councillor, Jonathan Miller, offered me recently the following salient observations:

- The internal perception that it is easier to attract public support for issues such as climate change and biodiversity than for complex and less tangible issues such as population growth, consumption and economic growth.

- The additional perception that tackling the drivers of unsustainability is more difficult conceptually, much harder to win in the long-term and that it is more difficult to identify ‘wins’ to supporters and members.

- A shift in the profile of ACF (and other ENGO organisation) activists and their collective culture from those who deeply understand and love the bush (e.g. bushwalkers and those with natural science degrees) to those with broader social issue concerns (and whom, in turn, are particularly reluctant to tackle issues such as immigration-driven population growth in Australia).

Reinforcing the first of these points, the US founder of the Post Carbon Institute, Richard Heinberg, has offered the following observation about environmentalists more generally in a recent blog (The Only Long-Range Solution to Climate Change, Museletter #343 September 2021):

It’s understandable why most environmentalists frame global warming the way they do (by targeting the fossil fuel industry). It makes solutions seem easier to achieve. But if we’re just soothing ourselves while failing to actually stave off disaster, or even to understand our problems, what’s the point?

This succinctly echoes exactly where my own thoughts have arrived at after over 40 years of involvement with environmental law and environmentalism. I have come to believe that:

- climate change is essentially a symptom (admittedly a very powerful one) of an underlying ‘growth’ disease; and

- that the current political system, which is the hand maiden of capitalism and completely in its capture, is incapable of producing an effective response to climate change, much less the deeper challenge of avoiding ecological collapse and transitioning to sustainability.

On the latter score, the efforts by ACF and other ENGO’s to scramble for the crumbs falling from the table at each, successive federal election, seem both flawed and largely fruitless. Over the years, even though ACF does not directly support any political party, it has often engaged in targeting marginal seats where the ALP may have a chance of defeating the Coalition. The relationship with the Australian Greens has remained strained. And, after watching on ABC TV this week the first episode of the series, Big Deal, which laid bare the lack of any safeguards with respect to corporate political donations, it is clear where the most powerful influences on federal politics come from.

So, this is why I am left feeling alone and isolated. Where are the voices to raise the larger sustainability agenda? What is the point of environmentalism, however well-intentioned, if it proceeds in almost deliberate disregard of this larger agenda? How can this agenda be pursued when those most likely to support it do not, or are not willing to, recognise it? And what is the point of trying to engage with the current, corrupt political system in which a large proportion of Australian citizens have lost all confidence?

My response to these questions, perhaps surprisingly, remains hopeful. There are many voices emerging globally in support of a deeper sustainability agenda, including some luminaries in Australia. Environmentalism has been a meritorious movement over the past fifty years but it now must be seen as one that is limited in its vision and incapable of promoting a deeper sustainability agenda. This agenda must and will emerge from other sources and directions. And the goal must be to promote this agenda through radical social, economic and political reforms – these will be the pathways of the transition to a sustainable future that embodies ecological resilience and a human civilisation that is living within its means.

To develop these ideas further, I am engaged currently in writing a book entitled The Great Transition: From the Anthropocene to the Ecolocene which I hope to get published in about eighteen months from now.

This article is reproduced with permission. It was published in the Sustainable Population Australia newsletter, issue #145, November 2021. It was written by Rob Fowler, Adjunct Professor at the School of Law, University of Adelaide. He was a vice-president of the ACF from 2008 to 2015.

How did the IPBES Assessment come up with the Figure of a Million Species at Risk of Extinction?

In May 2019 the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) published its global assessment of the state of the earth’s biodiversity and its prospects for change up to 2050. This is the first such report since the landmark Millennium Ecosystem Assessment published in 2005. The IPBES Assessment is the outcome of negotiations by 134 governments using data provided by 500 biodiversity experts from over 50 countries.

The aim of the IPBES Assessment is explained by its chair, Sir Robert Watson:

The loss of species, ecosystems and genetic diversity is already a global and generational threat to human well-being. Protecting the invaluable contributions of nature to people will be the defining challenge of decades to come. Policies, efforts and actions – at every level – will only succeed, however, when based on the best knowledge and evidence. This is what the IPBES Global Assessment provides.

It examines causes of biodiversity and ecosystem change, the implications for people, policy options and likely future pathways over the next three decades if current trends continue, and other scenarios.

My question is how did IPBES work out the number of species existing and at risk of extinction?

How many species are there?

Several different approaches have been used to estimate the actual total number of species on earth. Frankly it is impossible to know the number with any reasonable level of precision. The various methods give a very wide range of answers – from 3 million to over 100 million. Most of the more recent estimates based on thoughtful approaches are in range of 5 to 20 million.

The main point is to understand the relative level of extinction that could take place. We are finding new species all the time. There are frequent reports of excursions into rainforest finding lots of new beetles or other insect species. New species are even being found in our local area, viz Julian’s Hibbertia.

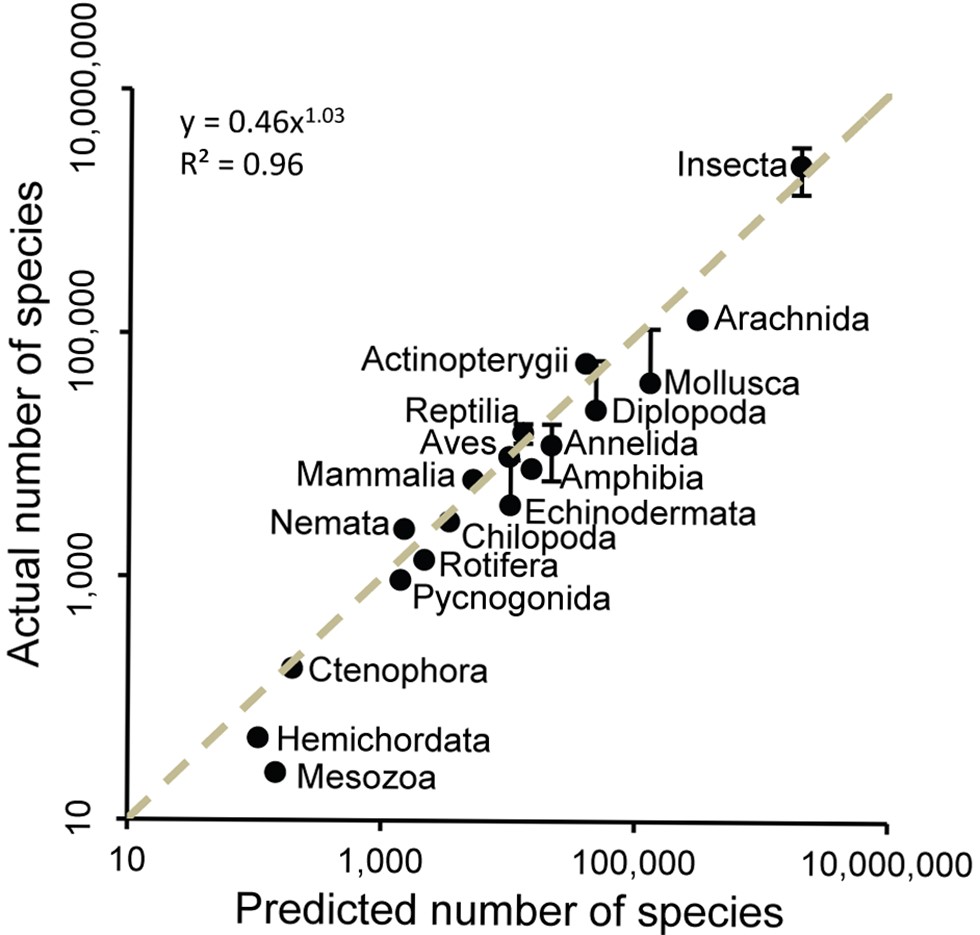

The report uses the results of a study published in 2011 [1]. The study uses data of past records showing how the knowledge of the number of phyla, classes, families, genii and species for each taxa have increased over time. For each level of the description hierarchy (phyla, class, etc) if fewer and fewer new types are being found then it is assumed that we are getting close to finding the final actual number. The method fits a regression line to the asymptotic graph of the known number over time to estimate the point where the line would reach the limit of increases. Then the phyla build into the number of classes and so on.

One argument in favour of this method is that species that are yet to be identified are living in small numbers or in niche areas so they are of less significance in terms of total life on the planet.

One argument in favour of this method is that species that are yet to be identified are living in small numbers or in niche areas so they are of less significance in terms of total life on the planet.

This approach was validated against well-known taxa such as mammals. When applied to all eukaryote kingdoms the approach predicted:

- ∼7.77 million species of animals

- ∼298,000 species of plants

- ∼611,000 species of fungi

- ∼36,400 species of protozoa

- ∼27,500 species of chromists

In total the approach predicted that ∼8.74 million species of eukaryotes exist on earth. Restricting this approach to marine taxa resulted in a prediction of 2.21 million eukaryote species in the world's oceans.

In spite of 250 years of taxonomic classification and over 1.2 million species already catalogued in a central database, the study’s results suggest that some 86% of existing species on earth and 91% of species in the ocean still await description.

How did IPBES derive the million at risk figure?

Species are defined as being at risk of extinction if their numbers are declining to the extent that the population may no longer be viable. They may not become totally extinct for a long time. For example, plants may live for many years but may not be reproducing.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species’ definitions of vulnerable, endangered and critically endangered are used to encompass the overall concept of being at risk of extinction.

The IUCN Red List is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of plant and animal species. It uses a set of quantitative criteria to evaluate the extinction risk of thousands of species. These criteria are relevant to most species and all regions of the world. With its strong scientific base, the IUCN Red List is recognised as the most authoritative guide to the status of biological diversity.

Currently the IUCN Red List status is that 36% of the 47,677 species assessed are threatened with extinction, which represents:

- 21% of mammals

- 30% of amphibians

- 12% of birds

- 28% of reptiles

- 37% of freshwater fishes

- 70% of plants

- 35% of invertebrates

that have been assessed.

Averaged across all the taxonomic groups of animals and plants that have had IUCN Red List assessments, about 25% of species are threatened. But the sparse data for insects so far suggest it might be lower – estimates range from 10 to 15% – so IPBES used a figure of 10% that might turn out to be conservative. If insects are three-quarters of animal and plant species, there are 5.5 million of them, of which 10% are threatened (so, more than half a million insect species are threatened). If 25% of the other 2.6 million species are threatened, that’s more than half a million non-insect species threatened. Hence the rounded total figure is about 1 million species at risk of extinction.

Are the headlines about loss of species meaningful?

Some very broad assumptions have been used in coming up with the figure of 1 million species at risk of extinction over the next few decades. One wonders if this is a meaningful exercise.

Are people going to take more notice of this announcement?

Is there a better way of illustrating the significance of the threat of massive biodiversity loss over the next few decades?

Maybe the percentages quoted earlier mean more, such as 70% of plants and 21% of mammals?

Another factor that may be more significant is the loss of biomass of plants and animals. Recent studies have pointed to the significant decline in biomass of insects. Dr Sanchez-Bayo from Sydney University pointed this out in a recent paper to the journal Biological Conservation [2].

Besides all the important functions that insects play in our ecosystems - such as pollination, or recycling nutrients - they are also an essential element in the food chain that supports life on our planet. When the insects go, the frogs, birds and mammals don't have food.

The IPBES Assessment is mostly devoted to describing the reasons for species decline and what should be done about it. The reasons are not hard to find: exploitation, land clearing, weed and pathogen invasion, climate change.

Currently biodiversity law and policy is inadequate to redress the situation. If we are to halt the continued loss of nature, then the world’s legal, institutional and economic systems must be reformed entirely. And this change needs to happen immediately.

Reference

[1] Mora, C; Tittensor, DP; Adl, S; Simpson, AGB; Worm, B (2011) How Many Species are there on Earth and in the Ocean? PLOS Biol 9(8): e1001127

[2] Sánchez-Bayo, F and Wyckhuys, KAG (2019) Worldwide Decline of the Entomofauna: A Review of its Drivers. Biological Conservation 232, 8–27

As the Election Looms the NSW Government makes some (Small) Environmental Announcements

It is estimated that there are fewer than 21,000 koalas left in NSW. The population may have reduced by more than a quarter over the past 20 years. The species is listed as vulnerable to extinction under the federal EPBC Act in NSW.

The major reason for the decline is habitat loss with the worst areas being in the Pilliga and South Coast. NSW is a heavily cleared landscape. Almost 40% of native forests and bushland has been removed since European settlement, and only 9% of remaining vegetation is in close-to-natural condition.

Eastern Australia is one of the world’s top 11 deforestation hotspots, along with the Amazon, Borneo and the Congo according to a report prepared by the NCC and WWF. Between 1990 and 2016, at least 2 million hectares of forest and bushland in NSW have been destroyed out of the total state area of 81 million hectares.

So what is being done about this? There are a number of decisions over recent years that will make the situation worse:

- As a result of the new biodiversity laws implemented in 2017, 99% of identified koala habitat on private land can be bulldozed.

- Last November the government commenced new logging laws called Integrated Forestry Operations Approvals. The laws reduce protections for forest wildlife, including koalas. One of the worst changes is the introduction of an intensive harvesting zone over 140,000 ha of coastal forest between Taree and Grafton. The intensive harvesting zone will see large-scale clear-felling legalised on the north coast for the first time. Because most of the trees will be gone, it’s likely that most of the koalas will be too!

- In December the Premier Gladys Berejiklian gave the green light to renew the Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) with the Commonwealth for another 20 years. RFAs are the mechanism by which the states are permitted to log native forests under accreditation from the Commonwealth. They are meant to balance the needs of the logging industry with conservation and public recreation. Conservationists argue that the RFAs have not been properly reassessed with a thorough scientific analysis of the values of native forests, for example for carbon storage and enhancement of catchment water.

NSW Koala Strategy

One positive development, albeit with limitations, is the government announcement last May of a strategy aimed at securing the future of koalas in the wild. $45m has been committed. It involves:

- setting aside 20,000 ha of state forest as koala reserves on the Central Coast, Southern Highlands, North Coast, Hawkesbury and Hunter

- transferring 4,000 ha of native forest on the North Coast to national parks

- allocating $20m to purchase prime koala habitat that can be added to national parks

However the strategy fails to commit to protecting areas known to be home to koalas from a major intensification of logging in state forests under new IFOA laws.

In early February 2019, as the election looms, some parts of the strategy have been implemented. A cattle property once used as a recreational dirt motorbike and horse recreation area has been bought by the NSW government to become part of the first national park to be gazetted in NSW in 11 years. It borders the Wollondilly River in the Southern Highlands and is about 3,680 ha. Actually 1,150 ha of this land is already protected so the addition is only 2,164 ha. There is no information about how much of this area is currently cleared and degraded from its previous use. How long before it becomes genuine koala habitat?

Great Koala National Park is a Better Idea

The National Parks Association has developed a proposal that will provide definite security for koala populations. This is for a 175,000 ha Great Koala National Park on the NSW mid-north coast, new national parks for the last remaining koala populations in southwest and western Sydney, or new national parks in other areas of known koala significance. The choice of the north coast has been confirmed as most effective by studies completed by the Office of Environment and Heritage, copies of which were obtained under Freedom of Information laws.

Funding Announced for Improvements to Popular National Parks

Another government announcement is for a $150m investment to improve access to existing national parks that includes upgraded walking tracks, better visitor facilities and new digital tools such as virtual tours and live-streaming cameras. The main investment is in the Blue Mountains and Royal National Park where visitor numbers have increased rapidly. This is all aimed at the tourist dollar, not conservation that is meant to be the main purpose of national parks.

Will there be an increase in funding for the National Parks and Wildlife Service to look after the additional reserves? After the massive cuts in funding of the service highlighted in previous issues of STEP Matters one wonders!

Removal of Feral Horses from Kosciuszko National Park has been Stopped

In December the NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee declared feral horses to be a key threatening process because they place dozens of species at risk closer to extinction. In response a spokesman for Environment Minister Gabrielle Upton said the government was preparing a plan of management that would:

identify the heritage value of sustainable wild horse populations and set out how those will be protected while maintaining environmental values.

That goal will be impossible to achieve.

Meanwhile, in response to the passing of the Wild Horse Kosciuszko Act, the number of feral horses being removed by current methods has been reduced to nil since August 2017 even though the Act was not passed until June 2018. The Invasive Species Council has obtained data showing that the peak number of removals was 600 in 2012.

The Nationals Parks and Wildlife Service in 2016 estimated there were 6000 brumbies in Kosciuszko National Park. Scientists estimate the population may grow by up to 20% a year. The drought though is believed to have curtailed brumby numbers.

Labor has committed to repeal the legislation to protect the brumbies.