As this is being written in late-August, Sydney is enjoying another near cloudless day. There’s been no rain for weeks and none is forecast. Rainfall at the observatory has been 3.2 mm for the month so far.

This is not unusual for August. August 2018s total was 7.8 mm; 2017s 24.2 mm. But it can be very variable; 2014s was 215 mm. Sydney’s record daily rainfall was on 6 August 1986 – 328 mm with a total of 448 mm with the inclusion of the day before and the day after.

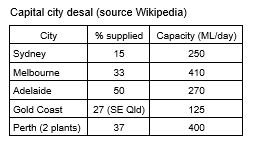

It has been dry and the dams are about 50% full and falling rapidly. As a result the desal plant at Kurnell is in operation to provide about 15% of Sydney’s water. Consequently our water bills are being increased from $2.11 to $2.24 per kL on 1 October.

Desal means desalination; i.e. the process of converting sea (saline) water to drinking water by the removal of salt. This is done by a process of filtration (reverse osmosis) but requires the water to be subject to massive pressure. It is very expensive in terms of energy consumption.

Brisbane (Gold Coast), Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide all got their desal plants as a result of the millennial drought in the early years of this century. They are only operated fully in drought periods – but see our update on Adelaide.

The Melbourne operation is quite marginal as the plant is located near Wonthaggi south-east of Melbourne not far from Phillip Island. It was impossible to locate it on Port Phillip Bay as water circulation in the bay is too low. So an 85 km pipeline had to be built as well and this of course gives rise to extra energy for pumping.

What about Perth you ask? This is the standout situation as this city depends on desal for about 40% of its supply year on year. Only about 10% comes from the dams in the Darling Ranges near Perth as most of this water is piped to the Eastern Goldfields (Kalgoorlie). One suspects that much of it is used by the gold mines.

The remainder is supplied by groundwater and recycling. The groundwater in future might become saline in which case it will be subject to desal too. This is also an issue in outback NSW.

The environmental impact of desal in Perth is somewhat mitigated by the use of natural gas to generate electricity.

Do Perth residents pay more than Sydney residents given that their water costs more to provide? The answer appears to be yes but it is not as simple as it might be. Perth has a sliding scale of charges. Like Sydney there is quarterly billing but the Perth charge depends on one’s annual consumption and can cost up to $4.442 per kL.

Sydney Water claims that its desal power is provided in an environmentally friendly way in that they have a contract with the 67 turbine Capital Hill Wind Farm, near Canberra.

This is a furphy. When the desal plant isn’t operating the wind farm feeds the NSW power grid. So when it is operating this feed is reduced and we have more reliance on gas and coal so increasing greenhouse gas emissions over what they otherwise would be.

A contrary view might be reasonable if we knew the pricing/contractual arrangements between Sydney Water and Infigen Energy, the owner of the Capital Hill Wind Farm. It may be that the farm would not have been developed without the desal requirement or not developed to the same extent.

CityLab article

Here are some excerpts from an article entitled A Water-stressed World Turns to Desalination.

The first large-scale desal plants were built in the 1960s, and there are now some 20,000 facilities globally that turn sea water into fresh. The kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with very little fresh water and cheap energy costs for the fossil fuels it uses in its desal plants, produces the most fresh water of any nation, a fifth of the world’s total.

Israel, too, is all in on desalination. It has five large plants in operation and plans for five more. Chronic water shortages there are now a thing of the past, as more than half of the country’s domestic needs are met with water from the Mediterranean.

Ecological impacts: It takes two gallons of sea water to make a gallon of fresh water, which means the gallon left behind is briny. It is disposed of by returning it to the ocean and - if not done properly by diffusing it over large areas – can deplete the ocean of oxygen and have negative impacts on sea life.

Another problem comes from the sucking in of sea water for processing. When a fish or other large organism gets stuck on the intake screen, it dies or is injured; in addition, fish larvae, eggs, and plankton get sucked into the system and are killed.

Contributed by Jim Wells

Update on Adelaide – November 2019

In another example of policy on the run like Snowy 2.0, PM Scott Morrison announced a drought relief package in early November. This includes a deal to crank up Adelaide’s desal plant in order to provide water for farmers to grow fodder for livestock.

Lin Crase, Professor of Economics and Head of School, University of South Australia in an article in The Conversation points out that this is not such a brilliant idea.

The plan involves the federal government paying the South Australian government up to $100 million to produce more water for Adelaide using the little-used desalination plant. Adelaide has continued to mostly draw water from local reservoirs and the River Murray, which on average has supplied about half the city’s water (sometimes much more).

But with federal funding, the desal plant will be turned on full bore. This will free up 100 GL of water from the Murray River allocated to Adelaide for use by farmers upstream in the Murray Darling’s southern basin.

The federal government expects the water to be used to grow an extra 120,000 tonne of fodder for livestock. The water will be sold to farmers at a discount rate of $100 per ML. That’s 10 cents per 1,000 litre.

The production cost of desalinated water is about 95 cents per 1,000 litres, according to a cost-benefit study published by the SA Department of Environment and Water in 2016. That means the total cost for the 100 GL will be about $95 million. So the federal government is effectively paying $95 million to sell water for $10 million: a loss to taxpayers of $85 million.

The discounted water provided to individual farmers will be capped at no more than 25 ML. The farmers must agree to not sell the water to others and to use it to grow fodder for livestock.

The amount of hay that can be grown with 1 ML of irrigation water depends on many things, but 120,000 tonne with 100 GL is possible in the right conditions. In the Murray-Darling southern basin lucerne hay currently sells for $450 to $600 a tonne. That would make the market value of 120,000 tonne of lucerne $54 to $72 million.

It means, on a best-case scenario, the federal government will be spending $85 million to subsidise the production of hay worth $72 million to its producers. One question is how will the government distinguish between the fodder grown with the megalitres provided at low cost and any other fodder harvested on the same farm that has been grown from rainfall or other irrigation water? How much will it cost to monitor and enforce such arrangements?

It seems a long way from the type of national drought policy Australia needs. It’s hard to see how a policy of this kind does anything other than waste a large amount of public money and disrupt important market mechanisms in agriculture in the process.

Contributed by Jill Green