At the start of the bushfires right up to December the government refused to talk about the influence of climate change on the drought and bushfires – ‘now is not the time’, etc.

Seriously!

Australia’s current climate change polices are woefully inadequate. So much so that they were ranked 57th out of 57 countries in a report by The 2020 Climate Change Performance Index prepared by a group of international thinktanks that looked at national climate action across the categories of emissions, renewable energy, energy use and policy.

On the assessment of national and international climate policy, Australia is singled out as the worst-performing, with the report saying the re-elected Morrison government:

has continued to worsen performance at both national and international levels.

As the fires worsened the government’s stonewalling became stronger still trotting out the tired old excuses; we are only 1.7% of world-wide emissions. we will make our 2030 target ‘at a canter’, we are doing better than other countries on a per capita basis, etc.

In response to the criticism the statement from PM Morrison that policies are ‘evolving’ does not engender confidence that any meaningful changes will be made.

I don’t want to bore the reader with a lot of technical detail but I will try to provide a brief fact check on progress in meeting emissions reduction commitments and the effectiveness of current policies in one place.

Emission Reduction Targets Explained

The reports from the Australian Department of Environment and Energy provide detailed explanations of the sources of emissions and projections through to 2030. The past data is constantly updated which can be confusing. I am using the latest report called Australia’s Emissions Projections 2019 published in December 2019.

Carry Over Credits

The original Kyoto Protocol commitments were based on data of greenhouse gas emissions during 1990. Australia managed to negotiate a favourable position whereby the base year data included emissions from land use, land use change and forestry. It just so happened that there was a high rate of land clearing in Queensland in that year so we had an unusually high baseline.

Australia’s first commitment for the 2008–12 period was an allowance for average emissions to increase by an average of 8% compared to 1990 levels, unlike most countries that committed to reduce emissions by at least 5%.

As it happened, we managed to over-achieve the target emissions and ended up with a carryover credit of 128 Mt CO2-e.

The next commitment was made to reduce emissions compared to 2000 levels by 5% to 2020. The way this is described implies that the level at 2020 should be 5% below the 2000 level. In fact, the requirement is that the total emissions over the 8-year period 2013 to 2020 should be 5% less than 8 times the level in 2000. The data cannot be quite finalised yet but it looks as though this commitment will be over achieved by around 280 Mt CO2-e. The total carryover is then of the order of 400 Mt.

The next target to focus on is the commitment made under the Paris Agreement to reduce emissions by 26 to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030. Again, this means that the total emissions over the 10-year period 2021–30 will be 26 to 28% below ten times the level in 2005.

The government’s own advisory body, the Climate Change Authority advised in 2015 that the science-based target should be between 40 and 60% below 2000 levels based on a goal of keeping global temperature below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

How are Emissions Tracking?

How are Emissions Tracking?

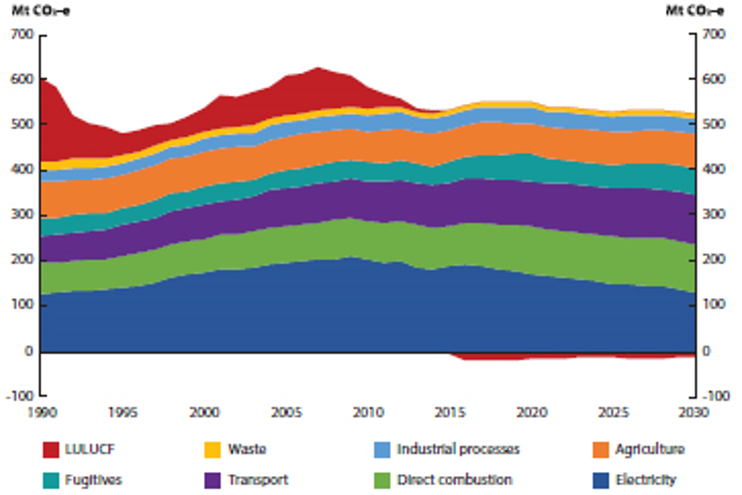

The latest government report states that the 2005 emissions level was 602 Mt CO2-e. So, the total emissions allowance for 2021–30 is 4,778 to 4710 Mt (602/1.26x10 to 602/1.28x10) (see figure which shows Australia’s emissions 1990–2030).

Emissions in 2020 are estimated to be 534 Mt and in 2030 511 Mt. The current projections are that emissions over the 10 years will be 5,169 Mt, at least 390 Mt over the commitment. We can only achieve the commitment if use is made of the carryover credits of 400 Mt.

Taking advantage of these credits is very poor form. No other country is doing this. Most of the rest of the world is genuinely taking action to reduce their emissions. What matters is emissions now and the path to zero emissions by 2050, not the easy ride we were given last century.

2050, not the easy ride we were given last century.

Climate Policies

The policies to reduce emissions are:

- Renewable Energy Target (RET)

- direct action under the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)

- safeguard mechanism

- National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP)

It doesn’t appear that these policies, particularly the ERF, are sufficient to achieve our 2030 target, particular given that many do not currently appear to have sufficient funding.

Renewable Energy Target

The original RET was established with the goal of increasing generation from renewable electricity sources compared with the level in 1997 to 20% by 2020. In practice the goal was expressed as 41,000 GWh of electricity generated per year.

The Abbott Liberal Government claimed the cost was too high and instituted a review by the Climate Change Authority. As a result, the target was reduced to 33,000 GWh by 2020 equivalent to about 23.5% of the current total of electricity demand.

Despite the dramatic rhetoric from the politicians supporting coal-fired power, the cost of providing incentives for renewable electricity generation has increased bills by only about 5%.

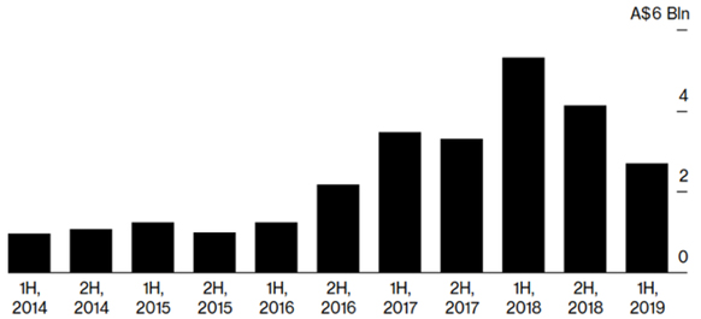

This target has been achieved already in 2019. No announcement has been made of any future policy creating great uncertainty in the industry. There has been a drop in new investment of nearly 21% in 2018–19 (see figure) at a time when the technology is developing rapidly.

This target has been achieved already in 2019. No announcement has been made of any future policy creating great uncertainty in the industry. There has been a drop in new investment of nearly 21% in 2018–19 (see figure) at a time when the technology is developing rapidly.

Several states have announced renewable energy targets so it looks as though it is up to the states to encourage new renewable energy projects. The take-up of rooftop solar is also still strong. Data from CSIRO and AEMO confirms that, while existing fossil fuel power plants are competitive due to their sunk capital costs, solar and wind generation technologies are currently the lowest-cost ways to generate electricity for Australia, compared to any other new-build technology.

Continued renewables growth also requires long-term planning of transmission infrastructure and storage technologies to ensure the distributed energy can be delivered where it is needed, and that reliability is maintained.

Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF)

The ERF is a voluntary scheme designed to provide financial incentives for businesses, landholders and communities to reduce emissions. As of 16 November 2017, the ERF had contracted 189 million tonnes of emissions reductions at a cost of $2.23 billion. Around $300 million remained for government purchasing of emissions reductions. Further funding of $200 million pa has been agreed over the next 10 years.

A range of projects to reduce emissions have been funded under the ERF so far. These include, for example, projects to replace Melbourne street lights with more energy efficient light bulbs, native forest and vegetation regrowth projects and the use of gas from waste to create energy. Many have been criticised as an inefficient way of reducing our emissions, amid suggestions that the government is paying polluters for emissions reductions that would have happened anyway even without the scheme – see STEP Matters Issue 188.

Safeguard Mechanism

The ERF includes a safeguard mechanism, which aims to ensure that emissions reductions achieved by the ERF are not nullified by rises in emissions elsewhere. The safeguard mechanism came into effect on 1 July 2016, and encourages large businesses not to increase their emissions above historical levels. The mechanism applies to emitters with annual emissions of over 100,000 tonnes CO2-e. The mechanism has been criticised as weak as there is too much flexibility to allow companies to shift or adjust their obligations.

Energy Productivity

There is also a National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP) that aims to encourage more productive consumer choices and promote more productive energy services.

Measures listed in the NEPP include improved vehicle efficiency and improved residential building energy ratings and disclosure. The NEPP could result in reduced greenhouse gas emissions in numerous sectors including transport, agriculture, industry and electricity.

The NEPP is expected to contribute over one quarter of the emissions reductions required to meet our 2030 target. However, as of July 2016, there does not appear to be any additional funding specifically allocated to implement this plan. The plan appears to have a very low profile.