STEP Matters 195

- Default

- Title

- Date

- Random

-

There has been much local angst about the idea that lights be installed on some of the Canoon Road netball…Read More

-

The Nature Conservation Council with the help of the Environmental Defenders Office won the case challenging the process of implementation…Read More

-

All members of the local botanical, bushcare and conservation communities have been deeply saddened by the sudden death of Noel…Read More

-

Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) are the mechanism by which the states are permitted to log native forest under accreditation from…Read More

-

The Australian government proposal, first floated in 2016, to remove tax deductibility status from donations to environment groups unless they…Read More

-

Australia’s rate of species decline continues to be among the world’s highest. Government decisions to promote population growth and resource…Read More

-

It has been a long drawn out process to develop a National Representative System of Marine Protected Areas (NRSMPA). In…Read More

-

We gardeners are often urged to ‘buy native’, especially nectar-producing flowering shrubs like grevilleas and banksias – they attract birds of…Read More

-

The preparation of STEP’s history by Graeme Aplin and the committee is progressing well and will be completed by our…Read More

-

STEP was a sponsor of this competition last year. Over 1,600 children entered and created some brilliant art works. The…Read More

-

FrogID is a project to help identify and survey frogs in your area. This is done via an app on…Read More

Canoon Road Saga Continues

There has been much local angst about the idea that lights be installed on some of the Canoon Road netball courts to allow matches on one evening and practice on three other evenings. STEP made a detailed submission highlighting the potential environmental impacts. Other submissions focussed on the lack of information about traffic and noise impacts and consideration of alternative sites.

In order to progress the situation, Councillor Jeff Pettett put up a motion at the meeting on 13 March for further studies to be completed particularly to consider additional suitable court locations. It is essential that other locations are considered to reduce the burden on Canoon Road and the travel required on congested roads. We hope a satisfactory solution will be found soon.

Biodiversity Laws Court Case

The Nature Conservation Council with the help of the Environmental Defenders Office won the case challenging the process of implementation of the land clearing codes.

The court decision was an opportunity for Premier Berejiklian to amend the bad laws her government had implemented and make some key improvements to protect habitat.

Instead, she has chosen to stick rigidly with the same destructive laws and ignore the science that highlighted the likely destruction. By the government’s own assessment, they will lead to a spike in clearing of up to 45% and expose threaten wildlife habitat to destruction, including 99% of identified koala habitat on private land.

Vale Noel Rosten

All members of the local botanical, bushcare and conservation communities have been deeply saddened by the sudden death of Noel Rosten on 26 February when he was knocked down by a car outside his letterbox. He was aged 85. The following details about his vibrant life have been taken from the tributes made by the Australian Plant Society (North Shore Group) and Hornsby Council.

Noel was an active member of many community groups within Hornsby Shire which included the Friends of Berowra Valley, Hornsby Conservation Society and the Australian Plant Society (APS). In the wider community, he was active with Easycare Gardening, National Tree Day and Clean Up Australia Day. He joined the Hornsby Council Bushcare program in 1992 and ended up running three bushcare groups.

Above all he loved bushwalking and growing native plants. With his wife, Rae, he joined APS North Shore Group in 1985. He and Rae developed a spectacular garden where Noel propagated native plants and orchids, many of which were donated for sale by the APS.

In the mid-1990s Noel and other members formed the Hornsby Herbarium to collect specimens of all the vascular plants in the Hornsby Shire. Once a week they went bush, listing all native plants on the track and collecting specimens for identification or scanning. These records now form the backbone of Hornsby Council’s herbarium.

Noel was a keen and talented photographer. He regularly entered the bushcare photograph competition with high quality photographs, many of which have been used in the bushcare calendar.

He was quiet, funny, gentle, always helpful, always willing to patiently share his knowledge He leaves a tremendous conservation legacy.

Members of STEP offer their condolences to Rae, their children and to Noel’s family and friends.

Native Forest Protections are Deeply Flawed, yet May be in Place for another 20 Years

Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) are the mechanism by which the states are permitted to log native forest under accreditation from the Commonwealth. The RFAs were designed not just to exploit this public resource but to incorporate conservation and recreation. They have a number of explicit aims such as establishing a reserve system to ensure adequate protection for forest ecosystems and threatened species, an ecologically sustainable logging process and to provide long-term stability for the forestry industries.

The National Parks Association (NPA) published a report in 2016 (OF Sweeney, Regional Forest Agreements in NSW: Have they Achieved their Aims?) that was highly critical of the RFA system. It said:

… the RFAs have failed to substantially meet their goals either wholly or in part.

and recommended that the NSW government should transition away from native forest logging.

As explained in the article below, the Australian government is planning to roll over 20-year extensions of the RFAs without any review as to the current ecological status of forests or reference to new information since the RFAs were first signed 20 years ago.

During the period provided for submissions on the renewal of RFAs the NPA was attacked by the Assistant Minister for Agriculture and Water Resources, Senator Anne Ruston claiming deliberate dishonesty in their campaign to end public native forest logging in NSW.

CEO of the NPA, Alix Goodwin has stated that:

It’s hard to see the senator’s letter as anything but an attempt to intimidate us, because we successfully challenged the government’s efforts to rush the RFAs through with minimum scrutiny.

The following article was written by Professor David Lindenmayer from the Fenner School of Environment and Society, ANU and was published in The Conversation on 23 March 2018.

State governments are poised to renew some of the 20-year-old Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) without reviewing any evidence gathered in the last two decades.

The agreements were first signed between the federal government and the states in the late 1990s in an attempt to balance the needs of the native forest logging industry with conservation and forest biodiversity.

It’s time to renew the agreements for another 20 years. Some, such as Tasmania’s, have just been renewed and others are about to be rolled over without substantial reassessment. Yet much of the data on which the RFAs are based are hopelessly out of date.

Concerns about the validity of the science behind the agreements is shared by some state politicians, with The Guardian reporting the NSW Labor opposition environment spokeswoman as saying 'the science underpinning the RFAs is out of date and incomplete'.

New, thorough assessments are needed

What is clearly needed are new, thorough and independent regional assessments that quantify the full range of values of native forests.

Much of the information underpinning these agreements comes largely from the mid-1990s. This was before key issues with climate change began to emerge and the value of carbon storage in native forests was identified; before massive wildfires damaged hundreds of thousands of hectares of forest in eastern Australia; and before the recognition that in some forest types logging operations elevate the risks of crown-scorching wildfires.

The agreements predate the massive droughts and changing climate that have affected the rainfall patterns and water supply systems of southwestern and southeastern Australia, including the forested catchments of Melbourne.

It’s also arguable whether the current Regional Forest Agreements accommodate some of the critical values of native forests. This is because their primary objective is pulp and timber production.

Yet it is increasingly apparent that other economic and social values of native forests are greater than pulp and wood.

To take Victoria as an example, a hectare of intact mountain ash forests produces 12 million litres more water per year than the same amount of logged forest.

The economic value of that water far outstrips the value of the timber: almost all of Melbourne’s water come from these forests. Recent analysis indicates that already more than 60% of the forest in some of Melbourne’s most important catchments has been logged.

The current water supply problems in Cape Town in South Africa are a stark illustration of what can happen when natural assets and environmental infrastructure are not managed appropriately. In the case of the Victorian ash forests, some pundits would argue that the state’s desalination plant can offset the loss of catchment water. But desalination is hugely expensive to taxpayers and generates large amounts of greenhouse emissions.

A declining resource

Another critical issue with the existing agreements is the availability of loggable forest. Past over-harvesting means that much of the loggable forest has already been cut. Remaining sawlog resources are rapidly declining. It would be absurd to sign a 20-year RFA when the amount of sawlog resource remaining is less than 10 years.

This is partially because estimates of sustained yield in the original agreements did not take into account inevitable wood losses in wildfires – akin to a long-distance trucking company operating without accident insurance.

Some are arguing that the solution now is to cut even more timber in water catchments, but this would further compromise water yields at a major cost to the economy and to human populations.

Comprehensive regional assessments must re-examine wood supplies and make significant reductions in pulp and timber yields accordingly.

The inevitable conclusion is that the Regional Forest Agreements and their underlying Comprehensive Regional Assessments are badly out of date. We should not renew them without taking into consideration decades of new information on the value of native forests and on threats to their preservation.

![]() Australia’s native forests are among the nation’s most important natural assets. The Australian public has a right to expect that the most up-to-date information will be used to manage these irreplaceable assets.

Australia’s native forests are among the nation’s most important natural assets. The Australian public has a right to expect that the most up-to-date information will be used to manage these irreplaceable assets.

David Lindenmayer, Professor, The Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Image: Current protections for native forests are hopelessly out of date. Graeme/Flickr, CC BY-NC

Foreign Donations Bill is a Threat to Democracy

The Australian government proposal, first floated in 2016, to remove tax deductibility status from donations to environment groups unless they use at least 25% of their donations for on the ground works has fizzled out. But now there is a new threat with a much broader reach, the Electoral Legislation Amendment (Electoral Funding and Disclosure Reform) Bill 2017. This so-called ‘foreign donations bill’ has been introduced in the name of protecting Australian politics from foreign influence. This poorly constructed bill would devastate the work of charities across the board if it goes ahead.

It is a great idea to limit foreign donations to political parties but this bill, as drafted, will have other much broader consequences for democracy in Australia. It could shut down the voices of community advocates, impose burdensome red tape restricting their work and it could severely limit the ability to do research and provide information to assist the general public to understand or participate in public debate.

All organisations that spent $100,000 or more on political activities in any of the previous four years would have to register as a ‘political campaigner’. Political expenditure is broadly defined and includes the expression of ‘any views on an issue that is, or is likely to be, before electors in an election’ whether it is during the campaign period or not. The cost of many charities’ advocacy on issues including homelessness, the age pension, low wages, refugees and the environment would be deemed political expenditure, forcing them to register.

The new status of ‘political campaigner’ comes with requirements to keep records to ensure donors of more than $250 pa are ‘allowable donors’ – such as Australian citizens or residents – and are not foreign entities. To comply donors would have to complete a statutory declaration and have it signed by a justice of the peace. It would be nigh impossible for groups to track individual donations and then ask for a statutory declaration. In any case many donors are likely to not bother. Other red tape requirements include the nomination of a financial controller that is liable for the charities’ disclosures, and the disclosure of the political affiliations of senior staff.

For donations from non-citizens or non-residents, charities would have to set up special accounts to keep revenue separate from other sources and ensure it was not spent on political expenditure. Breaches of these rules could trigger fines of more than $50,000.The ultimate effect for charities will be a set of complex, cumbersome and costly administrative requirements.

An example of an organisation that would be affected is the World Wildlife Fund that has over a number of years been strong advocates for Australia leading on conservation measures in the Antarctic. Their ability to advocate for that cause is only possible in large part because of funding from international donors and they will be restricted or banned from doing that.

Constitutional law experts have warned that the law is likely to be unconstitutional

Postscript

There has been a strong campaign against the proposed law from charities in all spheres. On 10 April the Senate electoral committee released a bipartisan report with 15 recommendations related to the bill. Notably, they called for the Australian government to rewrite parts of its foreign donations bill, which would remove some of the contentious elements related to charities funding. If these recommendations are agreed the bill will still create new obstacles for charities speaking out for the people they represent. Charities are still calling for the bill to be totally redrafted.

New Alliance to Push for Strong National Environment Laws

Australia’s rate of species decline continues to be among the world’s highest. Government decisions to promote population growth and resource exploitation (mining and agriculture) are accelerating this trend. Often governments are able to ignore their obligations to protect and conserve threatened species because of weak national environment laws. Governments are reversing hard fought gains as evidenced by recent decisions to relax land clearing laws in NSW and the reduction in marine sanctuary protections.

Australia’s environment protection laws are not working. An alliance of environment groups has been formed to push for a total revision of the federal laws and administration systems to stem the trend of loss of biodiversity and degradation of the environment. Leadership is needed at the federal level to ensure a coordinated approach. Maybe under the current coalition governments the chances of this being achieved are low but the approach provides guidelines for a way forward.

Places You Love Alliance

This alliance, called the Places You Love, has been created by 40 national groups guided by the work of the Australian Panel of Experts on Environmental Law. The Alliance follows the principles of collective action to achieve greater outcomes for nature than could be achieved by a single organisation.

Birdlife Australia, a member of the Alliance published a report in February 2018 called Restoring the Balance: The Case for a New Generation of Environmental Laws in Australia. In the foreword Nobel Laureate Prof Peter Doherty states:

Even when there is strong scientific evidence of actions that will cause harm, Australia’s poor record of environmental monitoring coupled with the ambiguity of key terms in legislation such as ‘significant impact’ means that science can effectively be ignored. Worse still, in some cases our Federal Minister has the power to use his or her discretion to override scientific evidence. Under exemptions, such as Regional Forest Agreements, actions that will impact on threatened species don’t even require Federal approval.

The Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act was passed in 1999. It is meant to be the key piece of legislation that ties together the roles of the Australian government and the states in order to create a truly national scheme of environment and heritage protection and biodiversity conservation The Act focuses Australian government interests on the protection of matters of national environmental significance, with the states and territories having responsibility for matters of state and local significance.

The matters of national environmental significance cover international obligations such as RAMSAR wetlands, nationally threatened species and ecological communities, Commonwealth marine areas, the Great Barrier Reef and water resources in regard to coal seam gas and major coal mining developments.

There are many inherent weaknesses in the Act and its implementation, meaning many neglected threatened species are simply being left to decline. Here are some examples.

Carnaby’s Black-Cockatoo

Federally listed as endangered, the Perth-Peel subpopulation of Carnaby’s Black-Cockatoos has declined by more than 50% since 2010, due to the ongoing clearing of foraging and roosting habitat on the Swan Coastal Plain. With more than 70% of banksia woodland now cleared, the species has become increasingly reliant upon pine plantations north of Perth to survive. But these are allowed to be harvested and are not being replaced.

Birdlife Australia has reported several times the decline in population and quoted legal advice that the continuing removal of mature pine plantations was in breach of the EPBC Act Recovery Plan and met the requirement for a significant impact on a matter of national environmental significance. The WA government has failed to take action demonstrating the inherent weakness in the legislation that relies in a large part on self-referral, opaque definitions of what constitutes a ‘significant impact’ and insufficient resources to ensure enforcement and compliance.

Swift Parrot

The Swift Parrot is critically endangered. With fewer than 1,000 pairs left in the wild, it is predicted to go extinct in the next 14 years. Loss of breeding habitat in Tasmania through logging and clearing that is allowed under RFAs is one of the greatest threats to the parrot’s survival, along with predation by introduced Sugar Gliders.

Unlike other industries whose activities may have a significant impact on nationally listed threatened species, logging and clear felling ‘in accordance with a RFA’ is exempted from national environment protection laws. In the absence of strong national leadership, recovery actions taken in one jurisdiction may be undermined by destructive practices in another.

Regent Honeyeater

The Regent Honeyeater is nationally critically endangered, having declined by more than 80% over the last three generations. Its decline is linked to clearance and degradation of its woodland habitat. The Lower Hunter Valley is known to be important for Regent Honeyeaters and is predicted to become even more important as climate change intensifies. Unfortunately, the woodlands and forests of the Lower Hunter are under significant threat from mining, industrial and urban developments.

In 2007 the Australian government approved development within the Tomalpin Woodlands. More recent evidence shows that this area is vital breeding habitat and there are other places where the industrial development could occur. The federal environment minister could but is not compelled to act on this new evidence.

Recovery Plans

When the EPBC Act was first passed into law, the listing of a species as nationally threatened triggered a legal requirement for the development of a national recovery plan; a document that captures current understanding of how present and past threats contributed to the species’ decline and the key actions needed to recover the species. While such plans are not directly enforceable, one would think the plan should impose measures to help protect a species, for example by identifying areas of critical habitat that must be protected. Importantly, the environment minister cannot approve an action that is inconsistent with a recovery plan.

In the five years or so following the introduction of the Act, a number of recovery plans showed clear intent to use the full powers and provisions of the Act but over time, recovery plans have become increasingly insipid as governments have sought to avoid strong prescriptions that might limit activities within a species’ range or require resources for the implementation of priority actions.

As the lists of threatened species have grown, funding for the development and implementation of plans has declined. Today, most listed species don’t have recovery plans. For those that do, recovery plans were mostly drafted long ago and have not been updated within the required five-year time frame.

Wish List of Reforms

The Alliance is calling for the reforms outlined below. However it is hard to imagine that they could be countenanced by the current government.

1. Create national environment laws that genuinely protect Australia’s natural and cultural heritage

The current system distributes responsibility across the federation, but no one jurisdiction is charged with coordinating efforts to protect our environment. A lack of nationally consistent monitoring and reporting makes evidence-based decision-making difficult for governments and increases costs for businesses attempting to comply with eight different, often-changing regulatory regimes.

The Australian government must retain responsibility for current matters of national environmental significance and protect them effectively. But national oversight currently is too limited and must be expanded to cover broader issues that impact on biodiversity and ecosystems such land clearing and water extraction.

2. Establish an independent National Sustainability Commission to set national environmental standards and undertake strategic regional planning and report on national environmental performance

The commission would also develop enforceable national, regional, threat abatement and species level conservation plans. Central to a new national environmental protection framework is the timely collection and disclosure of environmental data and the provision of independent and transparent advice on planning and approval decisions.

3. Establish an independent National Environmental Protection Authority that operates at arm’s-length from government

The authority’s role would be to conduct transparent environmental assessments and inquiries into development proposals as well as undertake monitoring, compliance and enforcement actions.

4. Guarantee community rights and participation in environmental decision making

Australian citizens have a right to be involved in decisions that will affect the use and health of our environment. Communities have been shut out or ignored by decision makers. Too often this has led to conflict between businesses and communities, and weakened community trust in government processes and institutions.

Hopes for Marine National Parks Protection Slashed

It has been a long drawn out process to develop a National Representative System of Marine Protected Areas (NRSMPA). In 1998 the commonwealth, states and Northern Territory governments committed themselves to establishing the NRSMPA by 2012. The Australian government affirmed this commitment at the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002.

The states are responsible for managing coastal waters out to 3 nautical miles offshore. Beyond that marine management is the Australian government’s responsibility.

The primary goal of the NRSMPA is to establish and effectively manage a comprehensive, adequate and representative system of marine reserves to contribute to the long-term conservation of marine ecosystems and to protect marine biodiversity.

After extensive consultation and scientific analysis the Gillard government declared a new network of marine reserves and plans of management that took effect in November 2012. The reserves cover 36% of Commonwealth waters with various levels of protection.

At the time there were protests from fishing industries but it was estimated by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences that only around 1% of the total annual value of Australia's commercial fisheries would be displaced.

The Abbott government came into power in September 2013 and in December suspended the declarations and management plans for these new reserves and instituted another review claiming that the science in the previous review was inadequate.

Draft revised plans from this review was released in 2017 and in March 2018 the final decision was announced by Environment Minister Frydenberg.

All the fears of the marine scientists that the science would be ignored have been realised. The draft proposals are to be implemented despite the protests exemplified by the statement below.

Government Decision

The government claims that the amended policy is a balanced and scientific evidence-based approach to ocean protection. However the marine conservation groups, such as Save Our Marine Life and WWF, have condemned the reductions in protection levels. In their view a particularly insidious form of partial protection is that of ‘habitat protection zones’ whereby only activities that affect the seabed are excluded. Such zoning ignores the important biological links between animals in the water column and the seabed. It allows commercial fishing activities within the marine parks that have already been assessed as incompatible with conservation in the government’s own risk reports. Indeed, such zoning creates the opportunity for industrial scale fishing within our marine parks by vessels such as the imported Dutch super trawler, the Geelong Star, that so many Australians rejected.

Sadly the Senate passed the new management plans on 27 March. Labor and the Greens could not marshal enough support from the independents to oppose the plans.

The following is a statement from the Ocean Science Council of Australia, an internationally recognised independent group of university-based Australian marine researchers, and signed by 1,286 researchers from 45 countries and jurisdictions, in response to the federal government’s draft marine parks plans.

We, the undersigned scientists, are deeply concerned about the future of the Australian Marine Parks Network and the apparent abandoning of science-based policy by the Australian government.

On 21 July 2017, the Australian government released draft management plans that recommend how the Marine Parks Network should be managed. These plans are deeply flawed from a science perspective.

Of particular concern to scientists is the government’s proposal to significantly reduce high-level or 'no-take' protection (Marine National Park Zone IUCN II), replacing it with partial protection (Habitat Protection Zone IUCN IV), the benefits of which are at best modest but more generally have been shown to be inadequate.

The 2012 expansion of Australia’s Marine Parks Network was a major step forward in the conservation of marine biodiversity, providing protection to habitats and ecological processes critical to marine life. However, there were flaws in the location of the parks and their planned protection levels, with barely 3% of the continental shelf, the area subject to greatest human use, afforded high-level protection status, and most of that of residual importance to biodiversity.

The government’s 2013 Review of the Australian Marine Parks Network had the potential to address these flaws and strengthen protection. However, the draft management plans have proposed severe reductions in high-level protection of almost 400,000 square kilometres – that is, 46% of the high-level protection in the marine parks established in 2012.

Commercial fishing would be allowed in 80% of the waters within the marine parks, including activities assessed by the government’s own risk assessments as incompatible with conservation. Recreational fishing would occur in 97% of Commonwealth waters up to 100km from the coast, ignoring the evidence documenting the negative impacts of recreational fishing on biodiversity outcomes.

Under the draft plans:

-

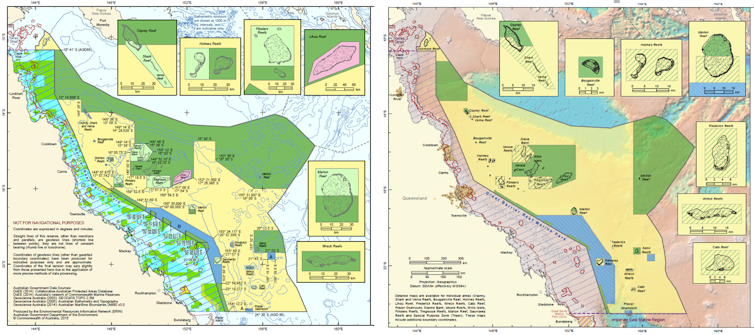

the Coral Sea Marine Park, which links the iconic Great Barrier Reef Marine Park to the waters of New Caledonia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (also under consideration for protection), has had its Marine National Park Zones (IUCN II) reduced in area by approximately 53% (see map below)

-

six of the largest marine parks have had the area of their Marine National Park Zones IUCN II reduced by between 42% and 73%

-

two marine parks have been entirely stripped of any high-level protection, leaving 16 of the 44 marine parks created in 2012 without any form of Marine National Park IUCN II protection

Proposed Coral Sea Marine Park zoning, as recommended by independent review (left) and in the new draft plan (right), showing the proposed expansion of partial protection (yellow) vs full protection (green). From http://www.environment.gov.au/marinereservesreview/reports and https://parksaustralia.gov.au/marine/management/draft-plans

The replacement of high-level protection with partial protection is not supported by science. The government’s own economic analyses also indicate that such a reduction in protection offers little more than marginal economic benefits to a very small number of commercial fishery licence-holders.

Retrograde step

This retrograde step by Australia’s government is a matter of both national and international significance. Australia has been a world leader in marine conservation for decades, beginning with the establishment of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in the 1970s and its expanded protection in 2004.

At a time when oceans are under increasing pressure from overexploitation, climate change, industrialisation, and plastics and other forms of pollution, building resilience through highly protected Marine National Park IUCN II Zones is well supported by decades of science. This research documents how high-level protection conserves biodiversity, enhances fisheries and assists ecosystem recovery, serving as essential reference areas against which areas that are subject to human activity can be compared to assess impact.

The establishment of a strong backbone of high-level protection within Marine National Park Zones throughout Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone would be a scientifically based contribution to the protection of intact marine ecosystems globally. Such protection is consistent with the move by many countries, including Chile, France, Kiribati, New Zealand, Russia, the UK and US to establish very large no-take marine reserves. In stark contrast, the implementation of the government’s draft management plans would see Australia become the first nation to retreat on ocean protection.

Australia’s oceans are a global asset, spanning tropical, temperate and Antarctic waters. They support six of the seven known species of marine turtles and more than half of the world’s whale and dolphin species. Australia’s oceans are home to more than 20% of the world’s fish species and are a hotspot of marine endemism. By properly protecting them, Australia will be supporting the maintenance of our global ocean heritage.

The finalisation of the Marine Parks Network remains a remarkable opportunity for the Australian government to strengthen the levels of Marine National Park Zone IUCN II protection and to do so on the back of strong evidence. In contrast, implementation of the government’s retrograde draft management plans undermines ocean resilience and would allow damaging activities to proceed in the absence of proof of impact, ignoring the fact that a lack of evidence does not mean a lack of impact. These draft plans deny the science-based evidence.

We encourage the Australian government to increase the number and area of Marine National Park IUCN II Zones, building on the large body of science that supports such decision-making. This means achieving a target of at least 30% of each marine habitat in these zones, which is supported by Australian and international marine scientists and affirmed by the 2014 World Parks Congress in Sydney and the IUCN Members Assembly at the 2016 World Conservation Congress in Hawaii.

![]() You can read a fully referenced version of the science statement here, and see the list of signatories here.

You can read a fully referenced version of the science statement here, and see the list of signatories here.

Jessica Meeuwig, Professor and Director, Marine Futures Lab, University of Western Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Tree Frog Apartments Available – Free!

We gardeners are often urged to ‘buy native’, especially nectar-producing flowering shrubs like grevilleas and banksias – they attract birds of course, even if these days mostly noisy miners and lorikeets. But a native species that's not for every garden but carries hidden gems is the Swamp Lily Crinum pedunculatum.

This is not a true lily but a member of family Amaryllidaceae, like Agapanthus and Clivea. It can be found in the wild, fringing coastal lagoons, and if you came on the Wyrrabalong walk you may have seen them scattered along the shoreline of Tuggerah Lake. They're also common at Maitland Bay in damp ground protected behind the beach dunes.

They are a large lily-like plant with a sheath of very long, broad, spear-shaped, scooped leaves around a solid, fleshy base. We've had one in the garden for about 20 years and you'd need a bobcat and a couple of big guys to transplant it. Ours usually puts up three spikes of large, faintly perfumed, purple-streaked, creamy white flowers in summer.

The scooped leaves collect pools of water at their bases that last for several days after rain and tree frogs seem to have no difficulty finding them. Two days out of three you can see one to three cute little Peron's Tree Frogs Litoria peronii snuggled into the soggy leaf pockets – we get them in all sizes and subtly varying buff-brown shades so a number of different individuals come and go; and also tiny, green Eastern Dwarf Tree Frogs Litoria fallax turn up on occasion.

Other inhabitants include crickets, huntsmen spiders and snails, and probably other creatures we don't see who come and go at night or when we're not looking. Another tree frog species, Litoria verreauxii, could also turn up, and I'm still tuning up my frog i.d. skills to pick the differences – colours can vary quite a bit.

Left: Peron's Tree Frog Litoria peronii in its temporary garden home. A noisy neighbour!

Right: Dwarf Green Tree Frog Litoria fallax on Swamp Lily leaf

Even if you don't have any Swamp Lilies in your garden you may still have suitable plants. A friend finds them in her bromeliads, though I don't know which sort. Gymea Lilies are a possibility too, as are other amaryllids – in fact almost any lily or sheath-like plant that retains water after rain is worth checking. And I imagine having more unusual natives like swamp lilies helps the survival of such moisture loving creatures through our long dry spells.

PS Swamp Lilies, like other amaryllids, are very prone to attack by Spodoptera caterpillars. Swarming with their longitudinal stripes they can eat a plant right down to the ground in a couple of weeks. It will recover via its rootstock but it doesn't look great in the meantime.

Written by John Martyn

Despite the dry weather there have been other frog encounters – the banner photo at the top of the page is a Green Stream Frog (Litoria phyllochroa) found on the Darri Track by Helen Logie.

STEP History – A Mapping Retrospective

The preparation of STEP’s history by Graeme Aplin and the committee is progressing well and will be completed by our 40th anniversary celebration on 22 July. This has given us an opportunity to reflect on the work that went into the development of our walking maps and the tremendous contribution of our volunteers. Below is an outline of the history and process of production of our maps.

There is still a regular demand for the STEP maps. Their broad coverage and detail make it possible to plan connections with public transport and interesting variations on the standard routes.

First Lane Cove Valley Map

It all started in the 1980s when a group of South Turramurra locals decided that a map was needed of the STEP Track and other local tracks. They went out checking the tracks that had been created over the years by various authorities and locals who found their own way to explore the bush. There was no national park in those days. They often met people who welcomed the idea of formal printed map. So this was the beginnings of the first Lane Cove Valley map that was printed in 1990 but it had a long gestation period of about 8 years.

The first draft was developed by geographer, Graeme Aplin and then Margaret Booth and the team of South Turramurra locals marked out the tracks which were then verified by a team of volunteers. This map covered the area upstream from De Burghs Bridge.

The final cartography and printing was done by the Central Mapping Authority in Bathurst and the Paddy Pallin Foundation provided a loan to cover printing costs.

The map was launched by Tim Moore, the State Minister for the Environment as a prelude to a bushwalk on 19 August 1990.

2000 and 2016 Lane Cove Valley Maps

In late 1997 the committee decided that a revision was needed because most copies had been sold, and changes had been caused by the 1994 bushfires and the M2 motorway. This time the map was extended to cover the whole Lane Cove River valley down to Greenwich Point. The map was launched in November 2000 by Peter Duncan, Director of the Centennial Park and Moore Park Trust.

John Martyn’s experience as a geologist was vital for the creation of the base map. Many hours or work were involved in building a full-colour base map stitched together from digital files provided by the NSW Lands and Property Information, air photos, satellite images and field observations. Roads, national park boundaries, local parks, hazards, natural features and many other details were meticulously inserted. Then the tracks were added and checked by John and a team of volunteers. Some volunteers did this with GPS and for wider tracks by Google Earth and air photos, others by simple navigation.

By 2015 it was realised that the map was getting out of date again. We had a good base to work on with the previous map. However John decided to extend the map detail to the west and south-west to cover more of the Lane Cove River catchment and more opportunities for walking connections with railway stations on the northern line. It is amazing how much has changed over 15 years so this again was a major exercise. Often it is harder to check for changes than to start from scratch!

It would not be possible to produce both maps without the help of our volunteers. Their work is much appreciated. Their names are listed below but please excuse us if any names are left out as it was hard to keep track of them all:

- 2000 map – Phil Helmore, Ralph Pridmore, Jenny Schwarz, Peter and Robin Tuft, Natalie Wood, Helen Wortham.

- 2016 map – John Booth, Debbie Byers, Robert Carruthers, Jill Green, John Hungerford, Adrienne Kinna, Andrew Lumsden, Ruaridh MacDonald, Natalie Maguire, Alan McPhail, Ralph Pridmore, Jim Wells, Natalie Wood, Ted Woodley.

Middle Harbour Maps

It became evident in the early 2000s that the Middle Harbour catchment offered numerous walks over a much larger area, and also that many STEP members who are keen walkers also lived in or near that catchment. Given the experience with Lane Cove mapping it seemed an easy choice to create bushwalking maps of that area. It also followed creation of Garigal National Park which merged large council bushland areas into one entity. The map coverage included a considerable area of suburbs carrying small reserves and linking larger bushland reserves, and included popular harbourside walks too, many in Sydney Harbour National Park. The end result was two double-sided sheets extending from Mona Vale Road to Greenwich and North Head.

The base for the Middle Harbour catchment was purchased from Lands and Surveys digital database and they also carried out the printing.

Volunteers were John Balint, Therese Carew, Bill Filson, Tim Gastineau-Hills, Gerald Holder, Simon and Joy Jackson, Bill Jones, Jan Kaufman, Kate Read, Jennifer Schwarz, Peter Tuft and Natalie Wood. STEP was also supported by the late Bill Orme, Graham Spindler and Leigh Shearer-Herriot (North Sydney Volunteer Walkers Group), NPWS and the relevant councils. Map cover pictures were watercolours by artist Janet Carter of East Roseville.

Children’s Threatened Species Art Competition

STEP was a sponsor of this competition last year. Over 1,600 children entered and created some brilliant art works.

The 2018 Threatened Species Children’s Art Competition will be open for entries between 4 June and 3 August 2018. Children from 5 to 12 years old are invited to unleash their creativity while learning about our threatened species.

Each child chooses one of over 1000 threatened species, researches, and then draws or paints it, and writes a short explanation of their work. Photographs of artworks and written explanations can be submitted on-line. Fifty finalists will be chosen for an exhibition in Sydney in September, with winners announced at Parliament House Sydney on 7 September, Threatened Species Day.

Citizen Science Opportunities

FrogID is a project to help identify and survey frogs in your area. This is done via an app on your phone whereby you can record the frog call, note your location and this information is sent off and collated. This is run through the Australian Museum.